ConnCAT | Politics | Science Park | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts

| Lucy Gellman Photos. |

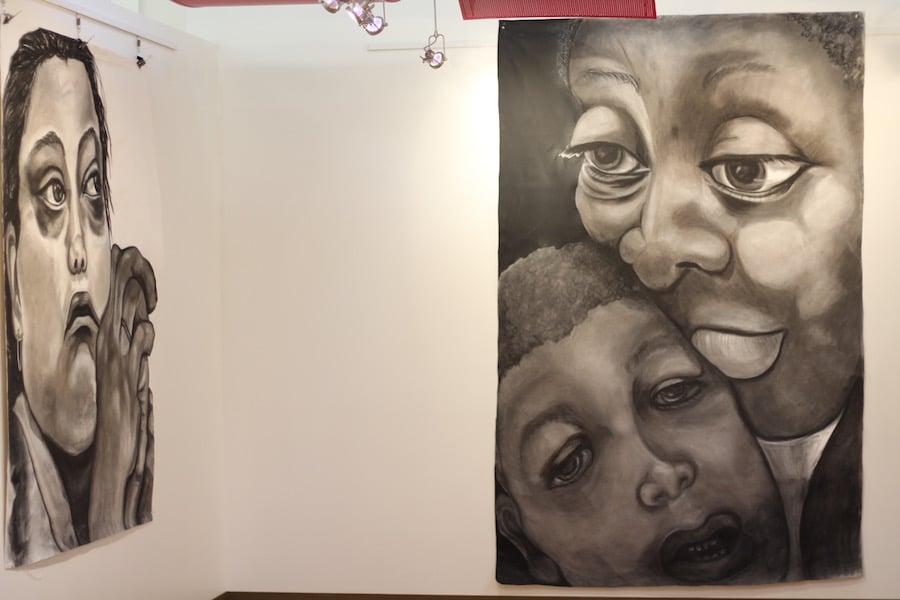

Two faces are colliding, soft skin on soft skin. At the left, a boy half-closes his eyes, lids heavy with the weight of something we can’t quite recognize. His mouth hangs half open, baby teeth still visible. Breath passes through. At the right, his grandmother presses her whole face into his. Her eyes, ringed with lack of sleep, are dulled pools of light. They look at him, and continue to see something beyond the frame.

The work comes from Bay Area artist Deborah McDuff, whose exhibition Impact on Innocence: Mass Incarceration runs at the Connecticut Center for Arts and Technology (ConnCAT) from March 8 through April 12. Installed in the ConnCAT’s second floor gallery space, the exhibition begins March 8 with an opening reception and community conversation. More information is available here.

It is, in part, a homecoming for the artist, who spent several years in New Haven and knows Carleton Highsmith, board chair at ConnCAT and one of its original champions.

Impact on Innocence, at its most basic level, uses visual art to explore the impact that mass incarceration has not just on those serving time, but also on the families and specifically children affected by their sentences. In the year 2019, McDuff noted, prison in America is still very much an industry that leaves devastation, covert labor, and gutted families in its wake.

“What happens to the mother who is bewildered by the onset of childcare with limited funds or assistance?” asks an artist’s statement that accompanies the exhibition. “What happens to the grandmother who has to rear another generation because her child cannot shoulder his or her responsibility? What happens to an immigrant deportee once imprisoned who has to leave their children?”

McDuff started the series in 2015, taking up charcoal for the first time. A multimedia artist and poet, she found that charcoal had a sculptural quality—messy and almost three-dimensional as she drew, smudged, drew again. As she dove deep on each piece, her subjects came to life, speaking from their long, unprimed and unframed canvases. Instead of a limitation, the monochrome became a language onto itself.

“Black and white was the best way to capture my message,” she said Thursday afternoon, waiting for labels to install with works in the exhibition. “I work on social justice issues. Let me shed light on something where people aren’t paying enough attention.”

“I wanted it to be raw,” she added. “These canvases are crooked and uneven—but the subject matter is crooked and uneven too. This is larger than life.”

Each piece has taken hours of research, McDuff leaving some of herself in the sleep-robbed eyes, long faces, furrowed brows and tiny hands of the people she depicts. On one wall, a subject titled “Latin Distrust” looks out at the viewer, eyes shifting as his lips fold downward. His neck and chest are a canvas of coded tattoos: a teardrop to show that he has killed someone, five-pointed crown for the Latin Kings, La Eme of of the Mexican Mafia, a dizzying spiderweb that translates to years in prison among tens of others.

A hardened anxiety etches his face: deep dips around the eyes, pockmarks where full cheeks should be, a jaw that sits completely still, as if it’s waiting for something. On the wall across from him, a woman prays. Her whole face fills the canvas, a study in sorrow as her clasped hands come before it. As he stares at the viewer, she looks heavenward instead.

In another nearby section of the show, McDuff has shifted the conversation to the hidden, uncompensated and under-compensated labor that transpires inside prisons, her subject seated at an an oversized sewing machine as she looks out at the viewer. To her left, her whole arm reaches toward the machine, seemingly too large for her body. Her elbow rests by a package that reads “SECRET,” a nod to the real-life story of female inmates sewing lingerie for U.S. chain stores. Her right hand wraps around the garment, a jagged piece of fabric caught in the needle of the machine. Her hair, like the fabric on which she’s been forced to work, stands rough at the edges, haloed in white. She looks miserable.

A figure drawn from McDuff’s research, the image taps into other meditations on social justice: printed ephemera calling for labor unions and protest in the U.S. and Mexico in the early and mid twentieth century, economic snapshots from the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and the height of Mexican muralismo, as similar subjects sprang to life in the public work of Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco.

But perhaps the most moving pieces in the show—although they are all moving—are those that depict the children impacted by incarceration. Across from the sewing figure, McDuff has rendered six children across two rows, their faces and hands pressed up close to bars and windows that keep them from their families. They are friends only by association, all members of a club in which they did not choose to take part.

On the left, a boy with big, melting eyes turns his whole face toward the viewer, his mouth a quiet, oblong O. No words come out. Around him, the faces shift: small and looking the viewer head on with raised arms, tiny hands and kid hair done six different ways. Twelve huge eyes stare out on the verge of tears. Only one child, in the lower right hand corner, is comforted by an adult.

That dread in the pit of one’s stomach echoes again and again in pieces like “Goodbye,” as a child turns toward the viewer, and a tiny white hand breaks through the darkness to his left. It’s there again in “Cambodian Deportation,” where the face seems to melt away with the wave and sway of the canvas, and across from the six faces, where a little boy holds his hand up to his chest, as if to show you that his heart is ripping in two.

Some of the children are inspired by stories that McDuff has read or heard. While completing a series on homelessness, the artist met a mother who was living beneath a bridge with her three boys, cooking hot dogs on a small hibachi machine. While the boys were “so cute, like three little butterballs,” the mother looked like she’d hardly eaten at all. She told McDuff that she had lost her job and chosen to live with them beneath the bridge, instead of putting them in foster care.

When McDuff was working on Impact On Innocence, she said she went back to that story and countless stories like it, working through the calculus of loss that children feel when their parents are taken away from them by external forces.

While McDuff, by her own estimation, is “not marching up and down the streets, which I have done,” she’s achieved the same result. The show is a call to arms, deeply feeling as hands reach, lips kiss and comfort, and children get caught in a loop of goodbyes. It is a needed reckoning for her viewers, who realize that good and bad, black and white, really do exist on the issue of prison reform. Indeed, she tells us, there is no grey area in a system of locking people up and putting their families on the other side.

“Children don’t choose their parents,” she said. “Why should they have to serve two life sentences?”