Arts & Culture | New Haven Pride Center | Ninth Square | Visual Arts | Life in My Days

| Detail, Lina Abojaradeh’s Rebirth at the New Haven Pride Center. The exhibition runs through the end of the month. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

The painting is stretched out across three panels, a bloom of blue, orange, and pink on the muted wall. There’s movement everywhere: sun ripping through a smudge of sky, a quiet city below, streams of light that pulse from one panel to the next. But it’s the image furthest to the right that catches the eye first, as a peach-colored body draws its knees up to its chest. It seems so small, so suddenly compact. As if we don’t know if it will be okay.

Lina Abojaradeh’s “Rebirth” is one of the works in the Beyond Suicidality Art Gallery at the New Haven Pride Center, up through the end of October. The exhibition signals a nascent partnership between the Pride Center and Waterbury-based Life in My Days, a peer- and youth- led nonprofit “built on a foundation of Peer Support, Disability Justice, Racial Justice, Divestment from capitalism and Patriarchy, Indigenous People Justice, and LGBTQ Justice.”

“It’s been wonderful to work with them,” said Life in My Days Founder and Executive Director Ahmad Abojaradeh in a phone call Tuesday evening. “It’s always wonderful to find spaces and organizations that are so deeply aligned with the vision that you have and the way you want to see the world go. It’s also always incredible when you find one of those spaces and all the barriers fall away.”

| Nada, Expectations. |

This month, that collaboration deepens with the exhibition, followed by a series of intensive, multi-day “Healing Fractured Heart” workshops in November. Ala Ochumare, who is the LGBTQ+ youth program office for the center, said that it has been particularly exciting to present the new programming for not just LGBTQ+ youth, but also the parents, guardians, caretakers, and teachers who may interact with those students each day.

“I want to put a component of emotional wellness into as much of the Center as I can,” she said.

The exhibition, meanwhile, offers another side of the fledgling partnership. Inside the Center’s basement gallery, artists reckon with themselves, probing the dark and often taboo underbelly of mental health. In “Rebirth,” Abojaradeh paints her own path through grief, mental illness and reconciliation, a knot of Turner-esque color tearing into the sky at the center panel.

One panel over, there’s an image of a figure—one doesn’t know if it’s the artist or not—pulling themselves into a fetal position, knees to chest. Their body, mostly the color of raw summer fruit, is lined with pink and red. Ropes of color sprout from the body, as if they are tens of tiny, rosy umbilical cords. A cyclone rages around them, the eye of the storm doubling as a sort of womb. Or maybe it’s not a storm at all, but a flower blooming back into being.

“This three-piece describes the different stages I have gone through, from the depth of the numbness that comes with depression, hopelessness, to the pain of transformation and finally to the hope of being reborn once again,” she writes in an accompanying artist’s statement.

| Detali, Perry Wu's Another Birth. |

Other works in the show hold that same complexity, bridging media as they hop from painting to photography, photography to oily pastel that seeps into its paper. In Perry Wu’s evocative “Another Birth,” Wu emerges from the open, perfectly round mouth of a dryer, wrapped in a billowing white sheet. His body flies through the air, weightless for a moment. His arms and head point skyward, back arched in the gentlest of C shapes. There is warmth there, seeping into the space around Wu to make room for his comfortable, half-naked body as it sheds its sheet.

There’s a trick of the eye there maybe—perhaps the photo has been taken with Wu standing in the dryer, gripping the ceiling above—but it doesn’t matter. The work, filled with sunlight on bare soft skin, retains its magic. The closer one looks, the more thrilling and miraculous the fact of Wu’s flight becomes.

The piece also inserts itself into the self-portrait genre, adding a narrative of mental health: Wu is a recovery support specialist with the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Connecticut, based in West Hartford.

“It symbolizes rebirth and the many cycles of growth and transformation after trauma and suffering,” he writes in an accompanying statement. “Each birth after periods of what felt like death has brought me closer to becoming my true self, who I willingly want to be despite my past.”

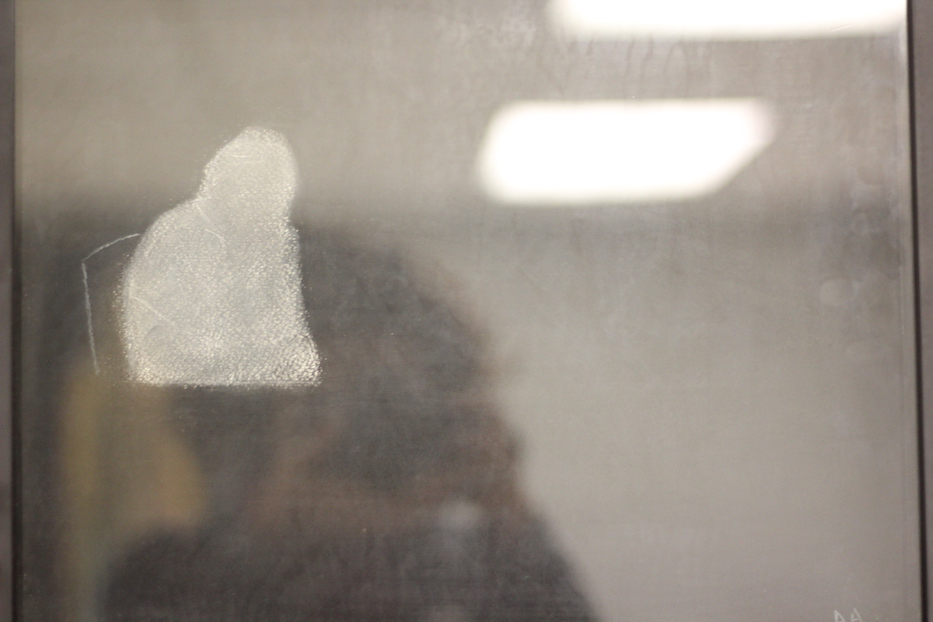

| Detail, AA's The Light at the End of the Tunnel. |

That tone carries over to other works that line the show, including artist AA’s oily, white-on-black “The Light at the End of the Tunnel,” in which the viewer can literally see themselves in the piece because of glare and black background. From long, deep fibers of the black paper a hunched figure emerges, not quite human and not not human either.

It is at once lush and austere, like everything lives and dies with this single interruption of light in the darkness. An accompanying label pushes that reasoning further, noting that “the light at the end of the tunnel is a reflection of the flickering light that is extinguished from suicide, and that the only light at the end of the tunnel will always lie inside us.”

And indeed, Beyond Suicidality is a call to—and celebration of—life that feels particularly resonant as young bodies, queer bodies, female-identifying bodies and Black and Brown bodies are subject to criticism, question and violence from their superiors, peers, and political and legal representatives. It urges viewers to take control of their mental health, seek psychiatric help, and check in on their friends.

In that sense, the show (and Life in My Days more broadly) is not a reaction to the current political moment as much as a call to build a supportive community that both understands and practices intersectionality. In a call Tuesday evening, Abojaradeh said they are excited to continue building that sense of community in New Haven, where there is currently a dearth of peer-led resources.

“The partnership is meaningful for me as a queer person and as a trans person,” said IV Staklo, an LGBTQIA+ activist and Hotline Program Director with Trans Lifeline who is also a board member with Life in My Days. “I’m really excited to extend the organization in a broader way to the LGBTQ+ community, and to the New Haven community.”

“Things that have consistently, historically gotten a pass in this country are being brought to light,” Staklo added when asked about a specific need for peer-led and supported initiatives under the current administration. “As artists, as peer supporters, as community leaders, that type of unity in a community is that thing that is going to not only help us win in a political sense, but also the communal sense.”

To find out more about the New Haven Pride Center, located at 84 Orange St., visit its website. To find out more about the "Healing Fractured Hearts" workshops, click here.