Music | Poetry & Spoken Word | Arts & Culture | Black Lives Matter | COVID-19 | Puma Simone

| Zoom. |

June 2020. The setting is downtown New Haven. The artist Puma Simone is watching six New Haven police officers arrest a Black man on Father’s Day. A white man sits on a stoop nearby, reading a book. He says nothing at all. Simone can feel something rising within them.

“Keep your head up!” they yell to the man. The cops, through the thick blue of their uniforms, seem annoyed.

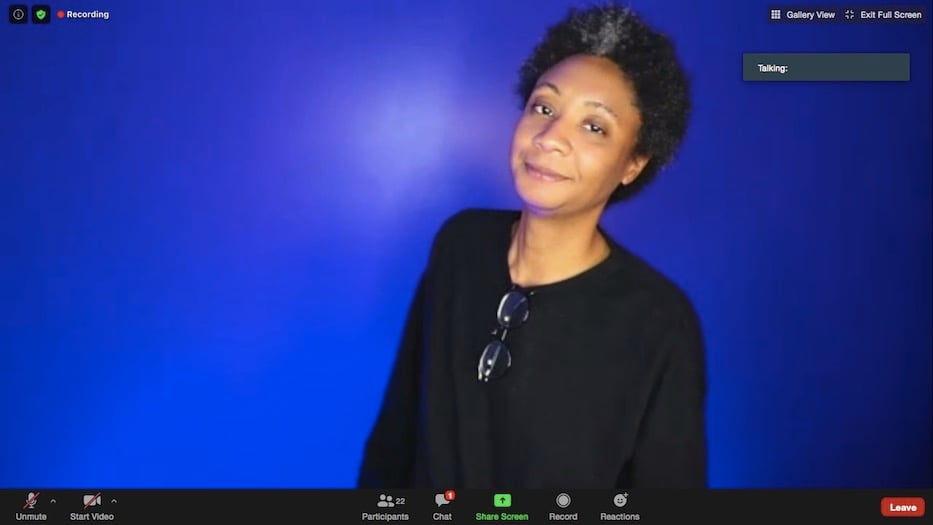

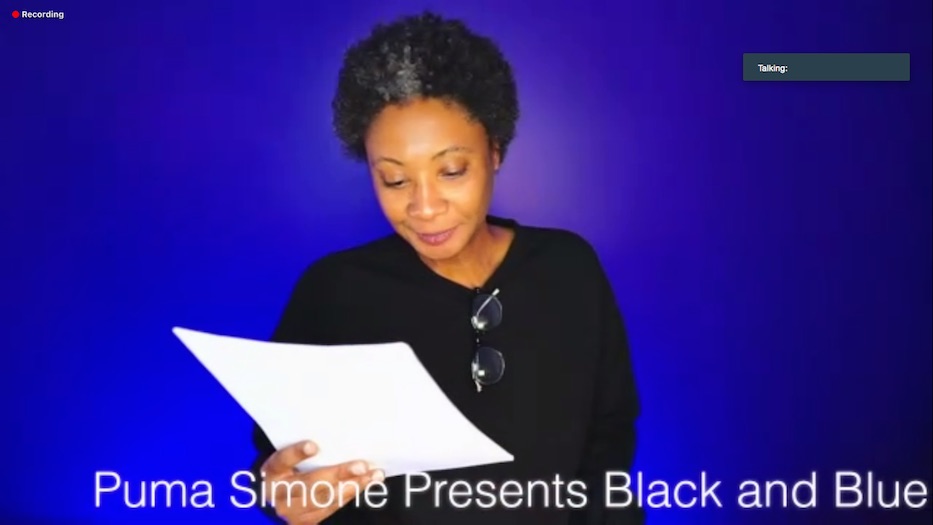

Simone told that story as part of Black and Blue: Part 2, the second half of a performance they premiered over Zoom in July. After two months of writing new material, they returned with a three-part, intimate document of New Haven, chronicling both the city and their role within it.

The event was livestreamed from the blue-walled studio of Top Secret Songwriter founder Marisol Credle. A few dozen people, from college friends to artistic colleagues in New Haven, attended. As Simone appeared against the wall, they seemed to radiate light, stepping in and out of what looked like a huge halo.

“My idea of being an artist and having a career as an artist was always that you had to do it a certain way,” they said during the performance. “The people that I idolized … I figured that you have to sacrifice your self care. The past years, I realized that that doesn’t fulfill me. What fulfills me is relationships. Being with people I love. Eating food that I love. My intention for tonight is to be comfortable with any mistakes I make.”

In doing so, Simone rolled out a rare kind of Zoom performance, seven months into this new world of online gigs: candid and comfortable, packed with lyrical swerve, deep wisdom, and a tempered respect for the city and its residents. Looking out at the two dozen attendees on Zoom, they opened the evening with a memory downtown, somewhere near Broadway Avenue.

They set the scene: six police officers gathered around a man, insisting that they had probable cause for his arrest. A fleet of blue, descending on Black skin. Just moments before, Simone had listened to an officer defend Jason Santiago, a fellow cop who was fired for excessive force after bodycam footage showed him dragging a man by his dreadlocks on Christmas.

The cop called it a knee-jerk reaction to the moment, which had also seen the state-sanctioned murder of George Floyd and a statement from Chief Otoniel Reyes that "what happened in Minneapolis was terrible, but it doesn’t happen in New Haven.” Something deep within Simone churned.

“I directed my attention at the cops,” they recalled, stepping close to the screen. Their eyes glowed. “This is what you do on Father’s Day?”

The cops were taken aback, as if Simone was one of the first people to speak to them during an arrest. Some of them appeared startled. They continued the arrest, some of them laughing, as Simone watched. On a nearby stoop, a white guy kept reading his book. As some of the cops pulled away, Simone began talking to an officer who remained. He puffed out his chest and identified himself as a sergeant.

“I pointed to the car,” Simone said. “What you represent is slave patrol.”

“I didn’t own any slaves,” he responded.

Simone wasn’t having it. Locking eyes with him, they dipped into the history of enslavement and the carceral state. They traced a through line from stolen people on stolen land to modern-day policing. They noted that the police department was a site of local trauma, where activists had been pepper sprayed for protesting police brutality. At some point, they became so nervous that their hands began to shake.

“So considering the history of this country, is it possible that we have all been traumatized?” they asked. “I watched his eyes dart back and forth.”

The sergeant softened. Simone saw a split second of understanding flash across his face. He walked away with his head down.

The story set a sort of tone for the evening. Simone’s writing has a way of inserting itself squarely into the moment, without ever feeling showy or performative. By the end of their first piece, they had waded into emotional exhaustion and the politics of performative allyship, circling back to the white guy who continued watching, silently, as they spoke to the police. They left room for mistakes, silences, and false starts, bridging the distance between screens.

In their second piece, they took on housing insecurity and the healthcare industry, cracking both open with the story of “a man named Henry, who is white according to the census.” Simone met Henry outside their own home, after finding him taking a nap on a rocking chair. At the time, Henry was intoxicated and exhausted. He told Simone that he just needed to sleep. Simone was sympathetic, but suggested he couldn’t sleep there.

It started weeks of conversations between the two that are still ongoing. When Henry saw Simone a few days later, he told them that recovery specialists at Yale New Haven Hospital had refused to help him because he had not been sober for long enough. Simone learned that he—like many New Haveners struggling with substance use disorder and housing insecurity—was a military veteran.

“It’s funny how America loves its heroes in combat boots, but hates when they drink all day on someone else’s stoop,” They said. The words hung heavy in the air.

“He’d smile and say, ‘I’m angry,’” they continued. “He told me about the people at the hospital, how he’d told them that he was in pain, how he was depressed, they cut off his social security, they wouldn’t take him. All he would say is, ‘they don’t want to help me.’”

The next time they saw Henry, it was late at night. Police were trying to arrest him as he yelled out into the blue dark. His voice had cut into Simone’s sleep; they'd come outside to see what was going on. Simone could tell that he was afraid and intoxicated. They calmed Henry down.

In the memory, they navigated an ocean of blue: the blue of law enforcement, the blue and teal of medical personnel, the blue of depression and the blue-black of 3 a.m., that hour that hangs between night and the first suggestion of morning. Before he left that night, Henry told Simone that he used to go bluefishing in the harbor with his father. It was how he knew New Haven.

Simone paused. They turned their attention back to attendees hanging on to every word. They asked aloud: had listeners ever considered students at the Yale School of Drama? For three years, they are temporary residents of New Haven. Then they head off to other places, taking tiny pieces of the city with them.

“Can you imagine how many characters have been built off of people in New Haven, with no reciprocity?” they said.

Black and Blue: Part 2 didn’t live inside any one genre: it hopped the boundaries between one-person show, spoken word, poetry, and memoir. As Simone entered their final piece of the evening, they reflected on their own journey to artistry. As they bloomed into performance, they’ve bucked their given name of Britney Anne Brevard—the name on birth certificates and passports, the name that their mother gave them—for the name by which they are known.

If asked, they are likely to say “that I am single, but somehow taken, heartbroken, really I’m an artist.” That “somewhere in my mind I am powerful/somewhere in my heart I am lovable.”

They told a final story to leave the audience grappling with. Months ago, Simone took a temporary shift at the Omni Hotel, serving food during a celebration of coeducation at Yale. Attendees made a beeline for food and alcohol “as if they had never eaten” in their lives. Management, meanwhile, told Simone and their colleagues that taking tips was forbidden.

It marked a stark contrast to the same city Simone knew, where Henry had to sleep on the street and food insecurity was rising, where cops could arrest a Black man while a white man kept reading nearby. Simone—who also joked that they were a terrible temporary employee—used it as a pivot to focus on their own intersections.

“I am queer, I am Black, I am a lover, I’m courageous,” they said before ending with a closing mantra. “Still I struggle with fear and still I’m still here.”

In the chat, Simone’s friends responded with an outpouring of support. A side panel that had been relatively quiet filled with a chorus of “Love you Puma!” and “You rocking this!”

“I'm still hurting but I'm still here,” wrote Sun Queen, with a flurry of music notes, referring to Simone’s closing lines (I’m still here/I’m still hurting but I’m here). “That's it stay here, feel, live & learn & sit still & listen.”