Creative Writing | Music | Poetry & Spoken Word | Arts & Culture | Black Lives Matter | Arts & Anti-racism | Puma Simone

| Puma Simone downtown, outside Maison Mathis. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

Puma Simone has been thinking a lot about physics. About electromagnetic radiation and the limits of the human eye. About the light that is reflected off a canvas, and the light that is absorbed into it. About how Black is not a color, but the absorption of multiple colors, holding infinities of light in its absence.

“Physics is figuring out how to live my life,” they said, stirring the chilled contents of a fruit-and-chocolate smoothie at Maison Mathis. “How to live holistically and with the least amount of harm to myself and other people.”

Simone, who is 33, is a New Haven based musician working on “Black & Blue: The Colonization Of Color.” After debuting the work on Zoom earlier this month, they are working on finishing and expanding the piece, a multimedia performance that includes song, spoken word, a cappella, and poetry. The project folds physics, whip-smart lyrics, and both personal and world history into a work that is very much a product of its time.

“I’m thinking about, like, the idea that color is a visual perception,” they said. “I’m still trying to figure out the words for it. But it’s like: If we’re gonna say people are Black or white, what does that mean? It was mind blowing to find out that they’re not colors. To have somebody say, ‘you’re this, you’re that’—it goes back to that perception of light and how it can be manipulated.”

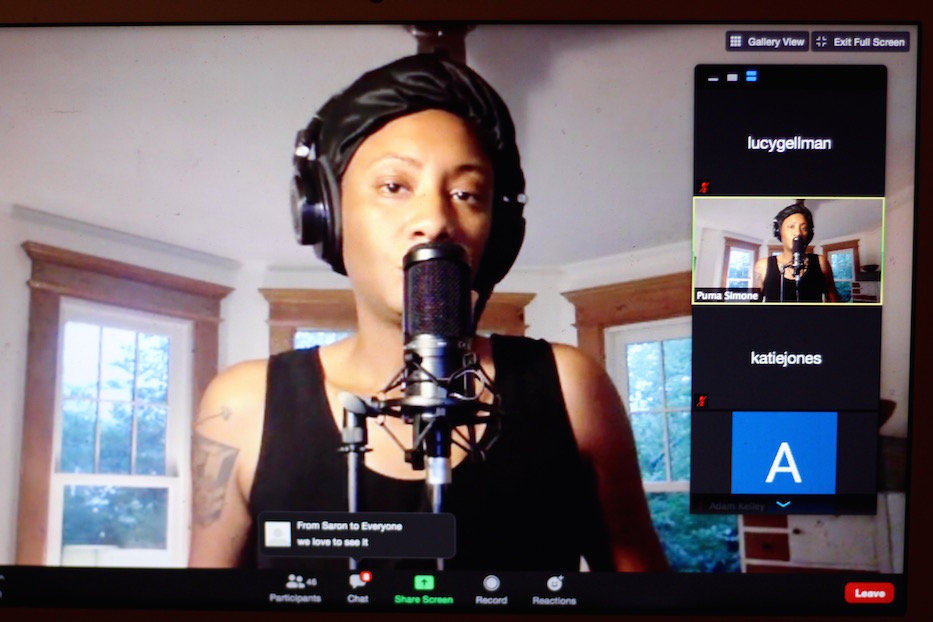

| Simone earlier this month, during their first performance of material from "Black & Blue." Zoom Screenshot. |

For Simone, whose foray into physics is relatively new, it feels like a natural step in three decades of music, spoken word, poetry, comedy and now fiction writing. Born in Fair Haven, Simone began making music when they were just five, and old enough to reach their first Casio keyboard. Their childhood had a soundtrack: their mom listened to gospel, while their dad dove into soul and jazz. For years, Sade was the hook, with a smooth sensibility that informs Simone’s practice to this day.

Each Sunday, Simone’s family drove to St James Unity Holiness Church, a white-and-red building that still sits at the intersection of Lawrence and Foster Streets. The gospel and loud, rhapsodic worship became Simone’s favorite part of the service. The elements were constants in their musical lexicon, a collection that eventually grew to include Lauryn Hill, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Kid Cudi, the Beatles and over a dozen New Haven artists.

It was during those years that they started writing poetry, with a focus on the natural world that has lasted into their 30s (during a recent interview, Simone noted that they would like to have a very long conversation with the Edgewood Park bear; it wasn’t a joke). Like physics years later, poetry was a device that let Simone navigate a changing world around them: their family moved from Fair Haven to Westville, transferring them from the city’s public schools to Catholic school and then back to public school.

“Trying to find myself was interesting,” they said. “I lived between two different worlds.”

By the time Simone was in high school, they knew they wanted to get out of New Haven. As a student and an artist, they felt a limitation that they now understand as a mix of the city’s size, its segregated arts scene, and institutional racism in the district, where the majority of teachers are white while the majority of students are Black and Latinx. In four years, they went through three different high schools, ready to leave the city by their senior year at James Hillhouse High School.

“I felt stifled, and really noticed how there was, like, a ceiling, in terms of all the different situations,” they said. “I felt stifled as an individual. College was my chance to express myself, find myself. Getting out of New Haven gave me the chance to do it.”

As a student at Boston College, they started performing spoken word in public for the first time. Encouraged by friends, they also began work as a DJ and music producer, teaching themselves as they went. They amassed equipment slowly, building a collection that took years before becoming the studio that it is today.

They also saw racism play out over and over again, from white professors inside the classroom to the music they heard at venues around the city. Inspecting their drink at Maison Mathis, they recalled going to a Kanye West concert, and listening to the musician invite the white people in the audience to use a derogatory slur as they sang along with the lyrics.

“It was like, do you even see me?” they recalled. “Who is this for? It’s not for me.”

It was during that time that Simone began to think more about color, and who was demonized because of it. By the time they got to senior year, they knew two things with complete certainty: they wanted to continue writing and making music—it was, and has continued to be, more of a need than a want—and they weren’t ready to return to New Haven.

“My interest in music, I don’t fully understand it myself,” they said. “It’s just something that, I guess. Music is—I just feel like it cuts through everything. I just feel blessed to be able to make it and share it with people. And also like, if I’m really in my head a lot, I just have to put on a song to motivate me. Just, every emotion. I think it’s in my bloodline somewhere.”

Simone went from Boston to New York, to teach in the South Bronx through the New York City Teaching Fellows program. They focused on music production, surviving off small jobs that were posted to Craigslist. Sometimes, they found themselves passing out flyers. Other times, they would manage a musician’s show or DJ an event for extra money. By the third year in the city, New York had lost its glow. Simone went back to the same impulse that populated their first poems: a craving for the natural world, equal parts respect and wonderment.

“After a certain point, it just didn’t feel natural, being in a place with no trees,” they said. “It started to weigh on me. And like, I gotta go underground to the subway, there’s rats everywhere. I don’t mind the rats, but it’s something about them being in this space with no air, underground. I felt out of my element.”

They returned to Connecticut in 2011, initially living with their grandmother in West Haven. Behind the scenes, their star was rising: they worked as a producer at South by Southwest (SXSW), produced music in the tristate area, and continued to quietly write their own music while working a day job that they hated. In 2012, they promised themselves that they would release new work for the first time.

When they did—and then brought it to an open mic in North Carolina—audiences received it like holy benediction. They haven’t stopped performing since.

“I was so blown away by how people received it,” they recalled. “I just wasn’t expecting it.”

Their entry into performance was the beginning of a new chapter for their work, and a boon to the city’s arts scene that has kept on giving. They became a fixture on College and Crown Streets, workshopping pieces at the People’s Arts Collective and Stella Blues. They brought their work to Cafe Nine, bringing down the house with a set early last summer.

They became enamored of the city’s symphony, from rolled-down windows blasting soca and reggaeton to the hum and growl of dirt bikes rumbling by their home downtown. They began thinking about the power they wielded with their words.

“It’s not me just performing a piece,” they said. “People are listening to me. So, it’s like, what do I want to say? What do I want to do? Where I’m going towards now is just being completely authentic. I don’t wanna dress things up. I just want to be able to identify how I’m feeling in my body and able to express that.”

In part, that’s where “Black & Blue” came from. The project originated last year, when Simone found themselves at the Yale Center for British Art to see Chromatic Crosscurrents: Blue and the British Empire. The exhibition, curated by Yale students, traced the British love affair with blue pigmentation through imperialism.

Simone sat for a long time in the show. Then they saw it for a second time. Then for a third. They learned about the British Navy’s adoption of blue uniforms through the use of indigo, native to India. Navy, in other words, became blue through a history of colonial violence. Not too unlike the fact people became Black and white as a device of classification, oppression, and colonialism.

“That was very interesting to me,” they said. “I was like—it [color] can change names, depending on who is talking. It was something about that exhibit that stood out to me. That made me wonder, not just what’s up with blue, but what’s up with color.”

They started to learn about physics, taking video tutorials that covered universal law, correlation and causation, color and refracted light. The more Simone learned, the deeper they dug. Their writing made room for it all, from an a cappella cover of the Beatles’ “Blackbird” to a poem that equated the Navy’s quest for color to Yale’s relationship with New Haven.

| Simone in June, performing virtually for the Arts Council's annual meeting. Their shirt comes from Sun Queen, a co-founder of Black Lives Matter New Haven. Zoom Screenshot. |

From the metaphysical realm,”Black & Blue” reaches into Simone’s own life, and into their experience of New Haven. Some of the works are wonderfully symbolic: when Simone notes “My lover’s favorite color is blue/a Navy man, he stands by the principles of light and truth,” they are talking about the $30 billion castle in the middle of New Haven.

When they explain that the lover is abusive—an oppressor who expects his catch to love him back—they are describing neighborhoods starved for jobs and businesses as 60 percent of the city’s grand list comes off the tax rolls.

The work is also some of the most vulnerable that Simone, who has never been one to mince words, has produced in a long time. Recently, they started seeing a therapist, who encouraged them to “sing to my heart.”A closing mantra that they now perform at each show —I’m still here/I’m still hurting but I’m here—originated from that directive.

So has a commitment to keep raising their voice. Earlier this spring, they brought it to performances for both the Arts Council of Greater New Haven and La Sala Femme. It transcends their art: their work is part of a thick webbing that includes Black Lives Matter, fighting the parallel pandemics of COVID-19 and racism, and deep, if tough, love for the city around them.

“If I’m walking down the street and I see someone being harassed, I just let them know that I’m there,” they said, recalling a fight that they had with a cop after watching an arrest on Father's Day. “I’m always using my voice. Even if I’m not on stage. I’m using my voice. It’s laborious, and it takes a lot of energy—and this is what it is.”

“I’ve seen how this city swallows artists up,” they added. They are a fierce advocate for local talent, with favorites that include Phat A$tronaut, chad browne-springer, Paul Bryant Hudson, Ro Godwynn, Salwa, Dyme Ellis, The New Mosaic, Mooncha, Z Bell and Thabisa.

As they sat back on Broadway Avenue, sips of cold smoothie punctuating their words, they looked like they were home. A July breeze rolled over the street. Passers-by chatted loudly, snippets of their conversation audible. Towards the end of the interview, Godwynn walked past and stopped to say hello.

Somewhere down Whalley, an engine revved back to life as a light went from red to green. It was as if the change in color sparked another thought, right on time.

“If people listen to any African, Black, Indigenous music, consume any Black or Indigenous culture through media, and you can’t stand up for Black people …” they trailed off. “I just want people to ask themselves that question. How is it possible for you to just love everything—the food, the slang—and you can’t stand up.”

“Using my voice, it takes a lot of energy,” they added. “It’s like, I don’t think you have to be an artist to use your voice or to stand up. You can do that on any day, at any time, any moment.”

Check out Simone's work at their website.