Long Wharf Theatre | Arts & Culture | Arts & Anti-racism | National Asian American Theatre Company

Jeremy Daniel Photos.

Sanam and Ariel are trying to make the data work. Around them, a dozen spiral notebooks sit open, documenting years of field research. Numbers dance on the pages. Ariel is sure the answer must be in there, hiding somewhere they just haven’t looked yet. But every time they run the regression analysis, there’s the same small discrepancy.

“If nothing is definitive, why can’t we err on the side of what we know to be true?” she asks. There’s not even a beat. “Because it’s fraud!” Sanam replies.

That quest for an absolute, capital T kind of Truth buzzes through Queen, a comedy about Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) running at Long Wharf Theatre through June 5. Written by Madhuri Shekar and nimbly directed by Aneesha Kudtarkar, the work probes not just nature and its discontents, but whether a friendship can withstand the broken-ness of academia, of late stage capitalism, of chemical interventions and science’s not-so-clear revelations.

It comes to the theater as part of the National Asian American Theatre Company’s (NAATCO) National Partnership Project (NNPP), for which Long Wharf is the anchor partner. After its run in New Haven, it will travel to A.R.T /New York from June 10 through July 7. Tickets and more information are available here.

Set at the University of Santa Cruz, Queen follows graduate students Sanam Shah (Avanthika Srinivasan) and Ariel Spiegel (Stephanie Janssen) as they finalize their research into honeybees, neonicotinoid pesticides, and a rise in Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD). Ariel, a community college grad and single mom who grew up as the child of beekeepers, is convinced that the chemical giant Monsanto is to blame. Sanam, an Indian mathematician who dreams of becoming the next Shakuntala Devi, has built a model to prove it.

Jeremy Daniel Photos.

In over six years of research in Dr. Philip Hayes’ (Ben Livingston) lab, the two have grown close, from afternoon happy hours and babysitting offers to trash talking their colleagues in the field. Now, their professional futures ride on their findings. There’s an upcoming presentation to the Ecological Society of America and pending paper in the peer-reviewed journal Nature. There’s potential pollinator legislation on the table. It appears that the two might be Hayes’ ticket to a bigger lab with more robust funding.

There’s just one problem: something in their final data set is throwing the experiment off. When it becomes clear that it’s more than a glitch in Sanam’s code, things begin to unravel quickly.

It’s watching how they unravel, a task carried by both cast and crew, that is the magic of this show. From the very beginning of the play, Shekar builds parallel worlds—or perhaps more aptly, combs—that fit snugly beside each other, parts of a collective, interlocking, and stingingly real whole. Her ability to couch all of them within CCD works, social universes crumbling as real animal and plant life hangs in the balance.

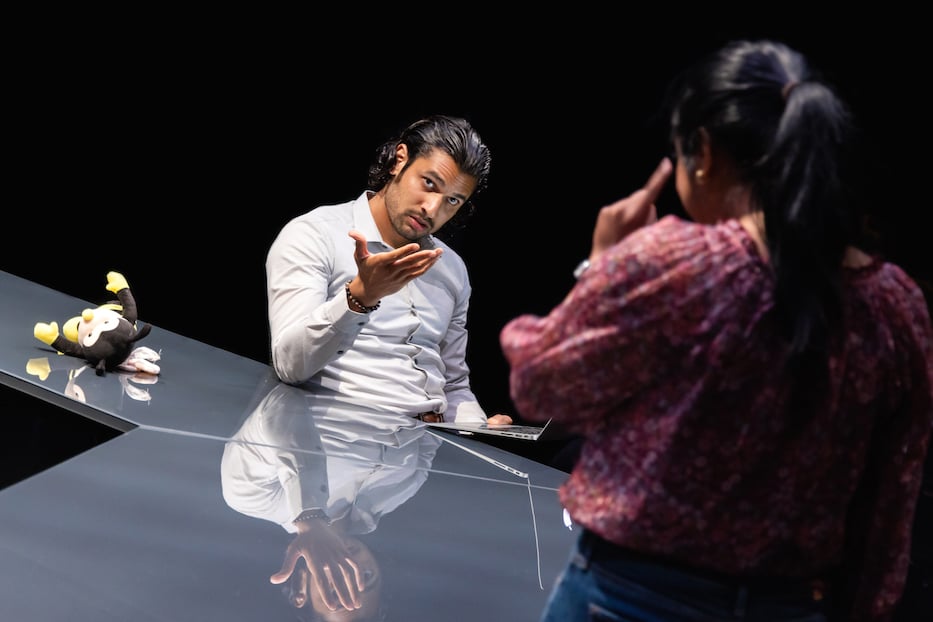

Jeremy Daniel Photos.

There is the lab, in which Sanam and Ariel start with a question about data, and end on one about ethics. There is Sanam’s love life, an arranged date with derivatives trader Arvind Patel (Keshav Moodliar) that turns into something far more complex as both defy stereotype. There is the ivory tower itself, split into hierarchies that label both Ariel and Sanam as outsiders at one point or another. And there is the world around them, with a population of tiny black and yellow pollinator friends that is running out of time.

What holds it all together is the women’s friendship, for which Srinivasan and Janssen seem made. As the two step into the show—it’s no mistake that Queen opens on the two huddled together at a party, and closes on them together outdoors—their chemistry crackles from the stage. In one such moment, Ariel leans over, and gives Sanam a sudden, unexpected squeeze that becomes a deep hug. The women’s bodies fuse for a moment. Then Ariel unlatches, and the play rolls on.

Srinivasan digs into Sanam’s single-minded dedication to the field of mathematics, and the clarity with which she sees numbers, rules, equations as the divide between right and wrong. When she begins to question everything she knows, it’s her face that tips the audience off, with an expressive range that plays up both the humor and drama of the show. She’s adept at mining the role for its depth, shape-shifting from a serious, sleep-deprived grad student to a strange rom-com character to a friend who has intended to wound because she has been wounded.

As Ariel, Janssen brings a red-hot, righteous kind of indignation to the stage, nailing the character’s total conviction in what is right. She is at turns fretful and fiery, that graduate student that many of us may have met at a Local 33 rally, pollinator festival or march for social justice. The audience, in turn, can feel the weight of this moment on her shoulders: she needs a job, reliable childcare, and an income stream that pays more than $30,000 a year. She doesn’t have a safety net to fall back on, and she doesn’t let Sanam forget it.

Jeremy Daniel Photos.

But it is when the two are together that the audience gets some of Queen’s richest material. As the data set fails to confirm their findings, Sanam and Ariel come to barbs with each other for the first time in over six years. On stage, their voices rise, just short of accusatory. Between their words—and sometimes in them—is the slippery divide between what is ethical and what is right. They sell it, their words flying across the stage with such propulsion that it seems they must have stingers.

If the two are the show’s heartbeat, Shekar does not leave any of the characters one dimensional. Moodliar in particular gives the audience a deliciously complex Arvind, with a need for creature comforts that comes from a deep, existential distrust of the world around him. From a bombastic, golf-playing Wall Street broski, Arvind blooms into many things: an unlikely thought partner, a mirror, a protective figure grappling with his own paternalism. Moodliar is especially good at listening for the pauses and comedic breaks, and the audience is luckier for it.

On Long Wharf’s stage the presentation is economical, but not overly sparse. Junghyun Georgia Lee, who also designed the set for The Chinese Lady earlier this season, has returned with a multi-part hexagonal design, including a mirrored floor and table in which characters are smartly reflected. Overhead, a hexagon glows yellow and blue (a nod to lighting designer Yuki Nakase Link) as setting shifts. A wall of honey-colored light shines on them from behind, soaking the stage in gold.

Lee’s set, which becomes an office, trendy restaurant, home interior, and applied math lab, works for the show. As tensions mount, stage hands smartly unlatch the tables from each other, pulling them apart to show that the comb is, indeed, dissolving at the seams. A sound design team has brought New Haven literally into the show, with recordings of bees from The Huneebee Project’s New Haven hives.

Jeremy Daniel Photos.

A sound design team (Daniela Hart, Noel Nichols, and Bailey Trierweiler) then manipulated those recordings, putting them through a series of audio filters as they became their own strange music. It works: a listener finds themselves more attuned to the way bees talk to each other than they may have ever been before.

The set also creates a container in which characters are able to interrogate not just obvious villains, but unexpected ones as well. Monsanto, which is very much killing bees in the real world, is an easy target. So is Wall Street, and the mathematical techniques that brought Sanam and Ariel (and everyone in the audience) the Great Recession.

But what about Arvind, whose life of excess covers up a much deeper sadness? Or the academy itself? Armed with her script and her own research, Shekar takes it on, dismantling a system in which those “fighting the good fight” are not immune from replicating the same systems of racism, sexism, and economic disenfranchisement unfolding at massive corporations. Kudtarkar is agile with the slow reveal, creating a tension among characters that simmers until it explodes.

When Hayes announces that “It is personal. It is political. It’s our future,” it’s suddenly not quite as clear whose future he’s referring to. It plays well in New Haven, where it’s hard not to think about the $43 billion bouncy castle in the middle of town, where graduate students are not yet recognized as employees for their labor.

Indeed Shekar has a talent for exposing, probing, and exploding false binaries, leaving a world that is far less black and white in their wake. Nowhere is this clearer than in the subject she’s chosen—honeybees, the gentle, fuzzy arthropods who are often misunderstood as a threat. Long after the lights go down and the stage no longer glows gold, the audience is left to think about their relationships with the tiny creatures, with each other, and with the world around them.

“Bzzaar” Brings Long Wharf Lot To Life

East Rock Apiary Owner Ian Knisley. Lucy Gellman Photo.

During a matinee performance last Sunday, Long Wharf channeled a sense of community with an “Outdoor Bzzaar” in the parking lot outside the theater, featuring two local bee champions. Beneath one tent, East Rock Apiary Owner Ian Knisley greeted visitors with samples of honey, harvested from hives in his Everit Street backyard. He runs the business with his dad, cancer doctor John Knisley.

For Knisley, beekeeping is about both tradition and sustainability. Growing up in New Jersey, his dad learned the trade from a Scottish beekeeper who had worked at Mount Vernon, George Washington’s sprawling estate in Virginia. On the Mount Vernon Property, the beekeeper had tended up to 100 hives. Knisley, who studied environmental geography at the University of Toronto, started with a much smaller number. Almost a decade in, they care for 15 to 20 hives.

The apiary’s honey is wonderfully complex, with blooms of flavor that begin on the tip of one’s tongue, and travel through rose and apple flavors, floral buds, and a dark, almost carmelly sort of finish. Its story overlaps with Queen: Knisley just finished a graduate degree at Duke University’s Nichols School for the Environment, and hopes to go into corporate sustainability.

Sarah Taylor and Gianna Strode. Lucy Gellman Photo.

A few feet away, Huneebee Project Founder Sarah Taylor and longtime employee Gianna Strode showed off a hand-painted bee hotel, pollinator seed packets, bee literature and Huneebee swag. Founded in 2018, the organization uses beekeeping to provide job skills to young people between the ages of 15 and 23. Participants, who are paid for their work, all have some level of experience with the protective or foster care system. There are currently hives in Fair Haven and the Hill.

18-year-old Strode, who has been working with the project for three years, said that she stayed with Huneebee not just for the work, but because she enjoys teaching fellow New Haveers about honeybees. In her three years with the organization, she’s noticed that bees are deeply misunderstood, often confused with wasps and hornets. In part, she blames popular media, from cartoon depictions of angry, stinging bees to news reports that show buzzing, agitated swarms clouding the air.

“They truly are not here to harm you,” she said.

Taylor, who created Huneebee as a path to healing, added that education is key. Each year, Huneebee may lose up to a quarter of its hives to seasonal fluctuations. If it’s too wet or too cold, bees don’t make it through the season, and the organization has to replenish its hives. In 2020—the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic—they lost every single hive. “They just knew,” she said of the bees.

Like Strode, she believes education is key to supporting the honeybee population. Not only are honey bees gentle and highly communicative: they’re responsible for much of the food humans consume, the flowers they marvel at, and the wax and honey that are as sacred as they are utilitarian. Without them, entire food systems will (and have already begun to) collapse.

“The more people see something as their friend and something they want to care about and nurture, they won’t be afraid of them,” she said.