Culture & Community | Downtown | Institute Library | Arts & Culture | History | Arts & Anti-racism

Akida Ouro-Adei. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Myla Generette wanted to learn more about the historical stereotypes of Black women and girls. Elsa Holahan felt the need to probe her history as a Moroccan American. Akida Ouro-Adei started with police and prison abolition, and ended with a mural. Tristan Ward looked at test scores and literacy rates, and built a program to help kids of color succeed on the path to college.

They are just four of nine participants in the Institute Library’s inaugural Social Justice Reader Program (SJRP), a new initiative that pairs adult mentors with Black high schoolers from across the city “to explore race as a social construct, racial justice, and racism” through text and rigorous scholarly study, according to the program’s mission. It both engages the Institute Library’s (IL) long history of social justice and folds that history into the IL’s present.

In mid June, students presented their findings at the 847 Chapel St. space, which sits sandwiched between a tattoo parlor and a bike shop. Roughly 40 siblings, parents, and friends attended.

“This represents six months of exploration, research and dreaming,” said SJRP Program Manager Dune Bryant, an operations manager at the Green Village Initiative in Bridgeport. “It has been six long months, and it has been worth it.”

SJRP Program Manager Dune Bryant. Lucy Gellman Photos.

The project was born in 2020, following the state-sanctioned murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minn. As protesters marched for racial and social justice across the country—including in New Haven—artist and educator Linda Lindroth watched the video of Floyd lying on the ground, calling out for his mother as a white officer ended his life. She was horrified. Her mind went not just to social justice efforts around the country but to literature and public history. As an artist, she has often brought literature, evolving technologies and the rich role of dissent into her work.

“I wanted to do something with books and libraries and reading,” she said. She brought the idea to the 10-person board at the IL, and then launched an advisory committee. With support from Lindroth, her friends and family, and a number of foundations, the organization was able to provide stipends for students and mentors, acknowledging the labor that went into their research. She praised Bryant for ultimately bringing the program to fruition.

On a recent Tuesday, student-researchers and their mentors filled the library’s back room, sitting shoulder-to-shoulder among the snugly packed shelves and potted plants. As they came to the podium one by one, the audience fell to a hush, ready to listen.

Myla Generette. Lucy Gellman Photos.

A rising senior at Metropolitan Business Academy, Generette kicked off presentations with an exploration of social norms and historical stereotypes of Black women and girls, looking to the past to understand her own present. Local journalist Markeshia Ricks, who served as her mentor (and who is the director of the Arts Council’s Youth Arts Journalism Initiative), noted how personal the research became. “Because of the skin that she’s in,” Ricks said, Generette’s work gave her a historical perspective on her own lived experience.

Speaking from a podium at the front of the room, Generette turned the clock back to 1789, when Sara or Saartjie Baartman was born in South Africa during Dutch occupation. It was here, she explained, that she found a new context around how Black women and girls are still fettishized, commodified, and held to different professional and personal standards today.

Often referred to as the “Hottentot Venus” during and after her lifetime, Baartman grew up in South Africa, and was in the early nineteenth century taken out of the country and placed on exhibition in Britain and Europe. For decades, she was treated as a captive object, rather than a human—the same process by which chattel slavery became normalized across the globe until the late nineteenth century.

That treatment did not end when she died, Generette continued. Baartman’s remains were first shown at Muséum d'histoire naturelle d’Angers, and then moved to Musée de l'Homme in Paris, where they were on display until 1974. She was not properly buried in South Africa until 2002, more than two centuries after she was first born.

Around the room, a few attendees sucked in air through their teeth; others offered knowing, deep and world-weary sighs. For Generette, it became a piece of a larger story that is still unfolding today.

Moving to another page on a website that she built, she looked to the Mammy stereotype, a caricature of Black women that reinforced notions of inferiority and subservience for centuries. She tied its long, harmful usage to current double standards, including the way Black women are expected to dress and wear their hair in the workplace.

“Even though there’s this constant weight on the shoulders of Black girls and women,” she said, her research also taught her that there’s an equally powerful resistance. She pulled up a TikTok pushing back against the “that girl” meme, explaining that there is one right way to be a Black woman in the world. As a few snaps and laughs rippled through the room, she clicked on a second video of the musician Rhianna, whose response to a question about her success within the context of her Blackness went viral.

“I mean, I’m a Black woman,” Rhianna began, looking into the camera as more snaps bubbled through the IL. “I come from a Black woman who came from a Back woman who came from a Black woman, and I’m gonna give birth to a Black woman. And so, it’s a no-brainer. That’s who I am. It’s the core of who I am, in spirit and in DNA, and I always stand up for what I believe in … and that’s how I’m gonna be. We are impeccable. We’re special, and the world is gonna have to deal with that.”

Generette set the tone for presentations that left no narrative stone unturned, from Holohan’s podcast series on New Haveners with roots in North Africa (listen here or in the video at the bottom of this article) to a tutoring initiative bridging the opportunity gap for Black and non-Black New Haveners of color. Throughout, attendees responded with applause, snapping from all sides of the room, and a few well-placed utterances of “okay!” and “yes.”

Amirah Harris and mentor Karen Jenkins. Lucy Gellman Photos.

A graduating senior at New Haven Academy, Amirah Harris dedicated their research to the prevalence of environmental racism in New Haven, particularly in Black and Brown, historically redlined and chronically under-resourced neighborhoods. As they came up to the podium, the pairing with Karen Jenkins, who serves on the city’s Historic District Commission, seemed particularly apt.

Originally, Harris said, they hadn’t heard the term environmental racism used in context. But growing up near Lighthouse Point Park, they knew that “every year, there was some kind of sewage leak in the neighborhood.” The more research they did, the more they learned about sewage and pollution leaking into the Mill River and the Long Island Sound, from which people still fish.

Part of the problem, they found, was a critical and long-term lack of investment in New Haven’s infrastructure (in this case, the East Shore Water Pollution Abatement Facility and the Greater New Haven Water Pollution Control Authority), which has created an environmental hazard for many of the city’s most vulnerable residents. In part, the problem is also due to climate change, through which New Haven gets shorter, heavier bursts of rain throughout the year. Sewage and stormwater go into the same tank, making it more vulnerable to overflow.

When Harris reached out to their alder, they said, they got crickets. They also discovered that sewage wasn’t the only thing plaguing Black and Brown neighborhoods—trash pileup, plastic pollution, and a lack of street sweeping were also all common and interrelated problems.

Their research, paired with a frustration in city government, resulted in a Social Justice Reader-spurred article. They will be keeping the work in mind this fall as they head to Florida for college.

“I’ve learned from this, really, New Haven has to do a better job of taking care of its citizens,” they said. “But also, there are hundreds [of cities] that have to do a better job. If you go to states like Arizona, California, a lot of POC [people of color] live in the desert, and they struggle to access water or any sort of air conditioning. It’s only getting hotter.”

“It taught me a lot about how to research,” they added of the program. “I’m much more committed to helping out my area.”

James Hillhouse High School student Elsa Holahan, who is working on a podcast series about New Haveners who are North African. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Other presentations included paintings, personal histories, and new programs just getting off the ground. Akida Ouro-Adei, a rising senior at High School in the Community who helped lead a district-wide walkout for student mental health in May, deepened their work on prison and police abolition with mentor and Elm City LIT Fest Founder IfeMichelle Gardin. Like Generette, they too turned back the clock, walking attendees through the very early origins of police and policing in America.

In the 1700s, they read from the podium, early policing efforts grew out of the double sin on which America was founded—the presence and forced labor of stolen people on equally stolen land. During those years, police worked to force Indigenous people off of land that was rightfully theirs, and to chase and capture enslaved people trying to emancipate themselves.

If that was the foundation, they asked, how could people of color ever expect police to protect them?

“It’s a never-ending cycle and we shouldn’t be okay with it,” they said. “Even if we called to indict, commit and incarcerate killer cops, it would barely work because it’s just a hyper-individualized distraction from the structural violence of the carceral state apparatus. We’re aiming for them to stop unjustly killing human beings.”

A self-described “artivist,” they motioned to With Liberty and Justice for Who? a large canvas with two handcuffs at the center, framed by the bars of a prison cell. Around the handcuffs, green dollar bills filled the background, each with a small police badge at the center where the image of George Washington or Alexander Hamilton might otherwise be. It took a moment to see hands in the cuffs, extended and fatigued.

Ouro-Adei explained that the work is intended to illustrate the tie between policing, prisons, and late-stage capitalism. It took them roughly a week to paint.

As they walked attendees through its symbolism, they also decried performative activism, police brutality, and legislation that gestures at reform, but ultimately does not change how police departments are trained and funded. They added that they see policing and the prison system not as rehabilitative, but punitive—making trends like generational poverty and recidivism more likely. Or in their words, “police and prisons are not the way and they have failed.”

“The justice system is not broken, it’s working exactly as it was intended to.” they said. “And police and prison reform cannot and will not work.”

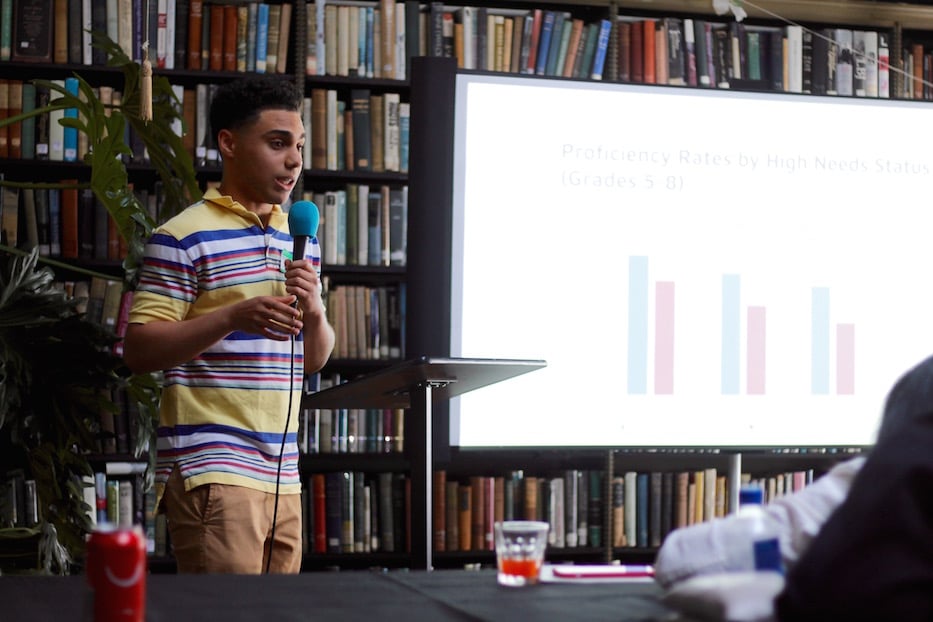

Throughout, students noted that the program helped them learn about not just their own histories—which often are not taught in schools—but themselves as well. Tristan Ward, a rising senior at New Haven Academy who worked with mentor Victoria McCraven, turned his own experience as a student and young educator in New Haven into the “College-Bound BIPOC Student Alliance,” a burgeoning college readiness resource for students of color.

His interest in education started when he was just five, and walked into New Haven Reads for the first time, he said. The organization helped him grow as a reader—and a chess player and student more broadly, he said. Years later as a counselor and teacher at Horizons at Foote, he noticed a disconcerting trend.

Students of color were just as smart as their peers, but when it came to standardized test scores, “they weren’t there academically,” he recalled. When Covid-19 hit New Haven, it widened the educational divide.

He decided that he wanted to pay it forward—just as people had once done for him. Before building a program, he looked to the Connecticut State Department of Education, which annually puts out a report on test scores, literacy, retention, graduation rates and more across the state. It confirmed his suspicions that Black students and non-Black students of color were getting left behind academically at a rate far higher than their white counterparts.

That was especially true for students who remained remote, he said. He also learned that getting students through their freshman year of high school was critical.

Tristan Ward. Lucy Gellman Photos.

“I want to see students not shut down, but have that smile on their face,” he said, recalling one student who had brought a math packet to him, and asked for help. “To make sure that they know what they’re doing and be in charge of it.”

His answer was the College-Bound BIPOC Student Alliance, which is just getting off the ground. Right now, he said, the alliance consists of college mentorship programs and academic enrichment, from free standardized test prep, pre-college resources and scholarship information to involvement in programs like Students for Educational Justice and A Better Chance.

He has currently created a survey to get the program off the ground, and reached out to New Haven Public Schools and New Haven Reads. Over the summer, he said, his goal is for 50 to 100 students to take it. He thanked McCraven for her help in shaping the program.

“He was really passionate about bringing people through the pipeline to prepare themselves to apply to college,” McCraven said. “I think the project shows an amazing amount of passion for the project, and something he’s also doing, experiencing himself right now … I’m so excited for how this project will continue.”

Working with artist and mentor Isaac Bloodworth, High School in the Community student Sayniel Sawmadal probed the history of the Great Migration and its implications beyond the Midwest, East Coast, and American South. Growing up with Liberian parents, she explained, she often wanted to know more patterns of migration to and within the U.S., from the flight of Black people from the South to her parents’ own choice to leave a war-torn Liberia.

“As a Black student, I’ve always wondered why my U.S. history classes never really explained what happened after slavery,” she said early in the presentation. Sawmadal learned about enslavement, Jim Crow, and segregation, she said, but she always felt like “a whole section of history was missing “ She wondered how Black Americans came not just to the East and West coasts, but back to West Africa, in attempts at repatriation that spanned the twentieth century.

When she was accepted into the SJRP, she started looking at old maps, tracing decades-old greyhound routes, patterns of manufacturing, industry, and job growth, and the history of redlining from the same era. Instead of the linear South-North narrative of the Great Migration that is often taught, she explored the travel routes of Black people to, from, and between the South, North, Midwest, American West, Mexico and Latin America, the Caribbean, Canada and Liberia.

What she discovered was a vast migration of Black Americans, from Canada-bound couple Thornton and Lucie Blackburn in the early 1800s to the 1917 race riots in East Saint Louis to the Pan-African congress in the middle of the twentieth century. The deeper she dug into her research, the more she discovered about her own history, and the history of Black Americans attempting to return to West Africa.

In the nineteenth century, it was President James Monroe—a slaveholder himself—who approved the purchase of land in Liberia for free Black Americans who wished to repatriate (if people have ever wondered why the capital is called Monrovia, Sawmadal said, they needn’t wonder anymore). Monroe’s gesture wasn’t entirely generous: it was part of a greater effort from the then-nascent American Colonization Society (ACS) to remove free Black people from what is now recognized as the United States.

But when Black Americans first arrived in the 1820s, residents of what is now recognized as Liberia (itself not formally founded until 1847) “were not happy with them moving,” Sawmadal said. They fought to defend land that was rightfully theirs. Black Americans—who were trying to heal from their own, recent and traumatic history of forced displacement—found that they were not welcome anywhere.

It made Sawmadal want to learn more about her own history, she said. In the 1980s, her parents were still young children when a military coup overthrew Liberian President William Tolbert and installed Samuel Doe in his place. In 1985, Doe remained in power after the country’s first election in five years. What followed, Sawmadal said, was a period of corruption and abuses of power that ultimately led to the Liberian Civil War in 1989.

In the 1990s, her parents fled from Liberia to Ghana, and then from Ghana to the U.S. Her mother was just 23 and pregnant with her. Years later, her paternal grandmother came to live with them, and the two would talk about Liberia on designated “cleaning days.”

"They [her parents] don’t really talk about the war because it was such a traumatic experience for them,” she said. The SJRP gave her a chance to dedicate time and thought to it.

“There was no more culture in my country,” she said. “They fought so long that rebels destroyed everything … I have no connections to my roots, so now I kind of feel like I can relate to how African-Americans here feel.”

Watch more from the presentation in the video above.