Baobab Tree Studios | ConnCAT | Storytellers New Haven | Storytelling | Arts & Culture | Black Lives Matter | COVID-19

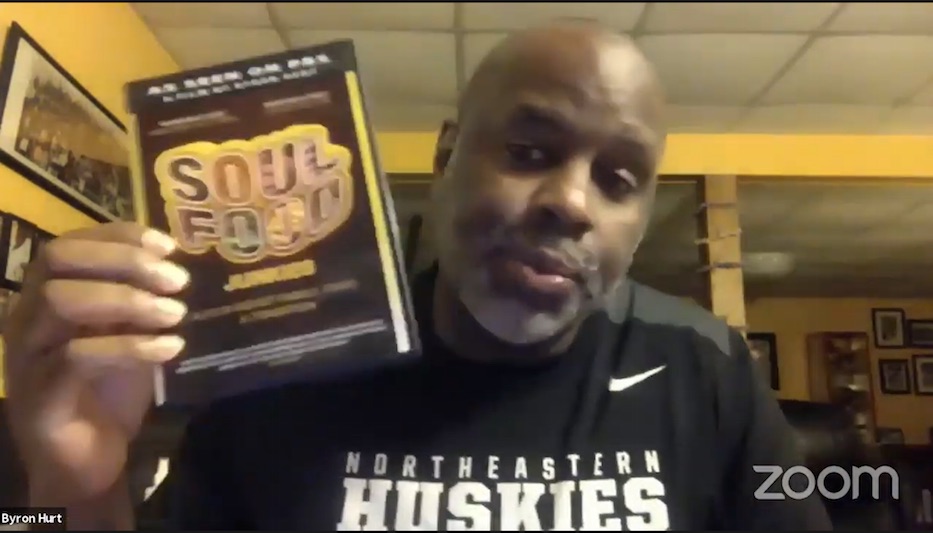

| Zoom. Not pictured: Behind-the-scenes help from Rev. Kevin Ewing of Baobab Tree Studios. |

Dr. Karen Dubois-Walton saw her life’s purpose while she was sitting in the middle of I-95. Byron Hurt spied his through a camera’s lens. Both grabbed potential by the hand and ran. On Monday evening, viewers got to witness those stories up close, told through their eyes.

Monday marked the last installment of Storytellers New Haven until September. The monthly group ended its third season with storytellers DuBois-Walton and Hurt. DuBois-Walton is co-founder of Storytellers New Haven and Executive Director of the Housing Authority of the City of New Haven. Hurt is an award-winning documentary filmmaker and host of the Emmy-nominated program Reel Works with Byron Hurt.

Kevin Walton, co-founder and host of Storytellers New Haven, thanked viewers for their continued support in the group’s virtual transition. He smiled and praised partners including Connecticut Center for Arts & Technology (ConnCAT), Baobab Tree Studio, and Rev. Kevin Ewing for their technological help. Lastly, he thanked DuBois-Walton and Hurt for bravely sharing their stories.

“I’m really excited about tonight,” Walton said. “In light of what’s going on between COVID-19, the protests, and the outrage of all that’s happening with police brutality, I think tonight is going to be about some healing, and it’s also going to be about some truth.”

Hurt and DuBois-Walton shared his sentiment wholeheartedly.

“Just like any Black person, not Black male, but any Black person, I’m deeply moved by the incidents that sparked the outrage,” Hurt said. “Of course, I’m moved by the galvanization and mobilization of Black people and allies who support the idea that we have to confront police violence, but I’m moved more by the countless stories of police violence against Black women and Black men. You know, I feel like most Black people, especially Black people who have reached a certain age, have seen these abuses of power happen over and over and over again, where no one is held accountable for the misconduct.

After a long pause, DuBois-Walton spoke.

“My heart has broken over the recent public acts of racism in Minneapolis and Kentucky and in Georgia, what we saw in Central Park and elsewhere, things that have really ignited this country—things that are forcing a level of reconciliation of our race and racism and racial equity in this country. It’s really in that light, in that spirit, that I offer my story this evening.”

Activism Through the Ages

DuBois-Walton took a deep breath, hands in her lap. Slowly, she looked up at her camera.

“Last Sunday, I found myself sitting in the middle of I-95 on the highway with my husband Kevin and our two sons Kevin and Caleb, with thousands of friends, acquaintances, and strangers.” DuBois-Walton’s eyes misted as she quietly spoke. “We were sitting there, bound together for George Floyd, for Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, for Christian Cooper, and far too many others’ names that are known and unknown. And as I reflected on the protest and our occupation of I-95, there was something special about that moment, seeing my now young adult sons take action of their own accord and walking into their own power.”

DuBois-Walton’s fists clenched as she described the visceral feeling of watching her sons become vehicles of social and political change. Throughout their childhood, she’d brought them to myriad protests, organizing efforts, and planning meetings. Now, with them in adulthood, it was the first time Walton had seen her sons participate in conscious volition. They were true activists, just like their mother.

And as she’d done so long ago, Kevin and Caleb joined the ranks of “The Only.”

Being The Only took many forms throughout DuBois-Walton’s life. The position was complex, ever-changing, and fluid. Sometimes, it meant isolation against waves of adversity, finding pride in her differences, and standing up for what she believed was right. Sometimes, instead of standing tall, it meant “bearing the discomfort of swallowing her voice.”

Her African American, Civil Rights Era parents had instilled these virtues in her and her sisters. The pair followed the best opportunities for their children, making them regularly move throughout New York State—still, the family resided in The Only everywhere they went. Racially, socially, and economically, somehow, they always belonged to The Only along some dimension.

DuBois-Walton first felt The Only’s touch during her childhood. In third grade, she’d sat in an all-girls private school in Albany, learning to multiply. Her class was split between two answers: One, Dubois Walton’s, and the other, her classmate’s own. Slowly, DuBois-Walton watched as her supporters dwindled. After a while, she was alone. Representing “The Only,” she stood tall. Her answer was correct. Later, her mother beamed with pride at her daughter’s report card. It read “independent thinker.”

Her independent thinking followed her into the sixth grade. This time, she was at a public school in rural Western New York. There, The Only reared its ugly head once again; she was the only Black person in a sea of white faces. She also belonged to one of the few Democratic-leaning families in the area. Her teacher polled the class around who they thought would win the presidential election. While most children raised their hands for Bob Dole, DuBois-Walton raised hers for Jimmy Carter. The teacher glanced at her and joked, saying, “the class preferred pineapples over peanuts.” DuBois-Walton had the last laugh.

“I have to admit that I gloated a little bit when I returned to class after the election,” DuBois Walton said. “I was happy to proclaim that Jimmy Carter was, in fact, President of the United States—peanuts it would be.”

It was still in Western New York when DuBois-Walton participated in her first, real protest. Her family had initially moved to the area so her father could become executive director of its state psychiatric center. While she was in high school, the hospital’s administration began deinstitutionalizing patients held for long periods into community-based settings.

Rather than redirecting funds from long-term hospital stays into those therapeutic sites, the state government chose to convert the psychiatric center into a prison. To DuBois-Walton, it had decided to take away her parents’ only source of income. She began writing letters against the effort addressed to Governor Mario Cuomo. She wore a t-shirt blazoned with “save the hospital” as often as she could.

“I remember going to school,” DuBois-Walton said. “I remember people mocking my t-shirt, and in some ways, most ways, they were mocking mental illness and anything associated with mental illness. I can remember being embarrassed about that, but also feeling convicted about it,” she added.

Despite the taunts of her peers, DuBois-Walton was numb to The Only’s sting. For once, others were supporting her cause. Many livelihoods in the area were being threatened. Much of the community was terrified at the prospects and implications of having a prison so close. DuBois-Walton smiled at the support.

It was only behind the walls of her own home that she heard the intense discourse, what the transition truly meant beyond her family and friends.

“I heard the more nuanced discussions about the lack of appropriate funding for mental health treatment, discussions about punishment being prioritized over treatment, discussions about how this prison meant that Black and Brown and Native bodies would be behind the walls—Native was significant in our town because this town abided by a Seneca Nation reservation. So, issues of the Seneca Nation, Native peoples, and sovereignty issues were part of our household discourse at that time. We had opposition and sort of aligned with the town. However, there were a lot of ways in which our alignment was rooted in some different understandings of the issues.”

Those conversations with her parents taught DuBois-Walton tenets of The Only that she’d follow for the rest of her life. She learned that she needed to look at issues from “many different sides.” She also learned that “folks could be on the same side of an issue for very different reasons.” She realized that decisions were made by people accountable to others and that she had the power to “make her voice known.”

And though the prison was eventually instated, DuBois-Walton realized how her parents balanced on a thin wire, The Only’s tightrope, what it truly meant to “speak up within a system that also fed her family.”

It was at this point in her story that DuBois-Walton paused and squeezed her eyes shut. She took in a deep breath and released it. After a moment, she continued.

“Some of you know that not too long after that, I lost my parents. They both died when I was 17.” Her misty eyes stared past the screen. “One died right before I left New York to go to college at Yale, and my mom died in October of my freshman year.”

The livestream’s chat stopped as if stunned into silence.

DuBois-Walton pushed forward. She began to explain how her life’s passion, activism, became her buoy in that traumatic year’s hurricane. There were many among The Only at Yale. Student-led activism was rampant. Students flooded Woodbridge Hall, protesting the construction of a shantytown by Beinecke Plaza. DuBois-Walton and her comrades fought for Yale to divest from companies supporting the economy of apartheid South Africa. Though unsuccessful, their campaign caused many administrators and staff to reconsider the university’s ethical responsibilities.

“I joined in, and for moments, I was able to forget my own pain, while I joined with other people who were trying to heal pain in a country halfway across the globe,” DuBois-Walton revealed. “I imagined that movement might be something like the movement that my parents had described to me about the Civil-Rights Era, and I felt connected to them in that. I connected to something bigger than myself.”

The spirit of The Only that lived and breathed in New Haven made DuBois-Walton stay. She became a clinical psychologist, able to give The Only a voice, yet empathize with all peoples. She and her husband raised Kevin and Caleb in a community that “raised its voice against iniquities,” New Haven, where residents “fought for all.”

In New Haven, the Walton family marched with the brothers and sisters of The Only. They marched with New Haveners for Malik Jones in April of 1997. They felt anguish protesting the tragic death of Trayvon Martin in 2012.

Now, DuBois-Walton and her family sat on the pavement of I-95. She looked up at her sons, Kevin and Caleb, trying to imagine a world that could look different. They were her legacy, her parent’s legacy, a legacy of activism and sacrifice.

DuBois-Walton closed her eyes.

“I end every work email that I send with the same quote, which is a part of a legacy. In the words of Martin Luther King: ‘The moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends towards justice, and I think we all play a part in bending it.’ Thank you.”

"Hip-Hop: Beyond Beats and Rhymes"

Hurt thanked DuBois-Walton for sharing her powerful story and began his own.

“If someone would’ve told me when I was 15 or 16 years old that I would one day become my own boss, make documentary films, and that I’d be a storyteller, I would not; I would never believe them!” Hurt threw his hands in the air. “It wasn’t within the realm of possibility that that would be my profession, my career, and something I’d be very passionate about!”

His eyes were wide, and he tapped his desk to punctuate each word. After a bit, he gave a low chuckle. “But when I look back at my life, I’ve always been a storyteller—I just didn’t know it.”

When New Yorker Hurt arrived at Northeastern University, he was young, bright-eyed, and energetic. For his entire life, he’d wanted to be a news anchor. He’d marveled at presenters like Brian Gumbel, Bernard Shaw, and Edward Bradley, worshipping them like gods. Hurt wanted to be in the news business, and he was sure Northwestern’s Speech Communication major was going to take him there.

Unfortunately, his bright-eyed gaze dimmed shortly after he entered. Hurt quickly became disillusioned within a major and peers that felt aimless. He struggled to grasp his dream in a space that felt too amorphous to “derive anything of real value or worth from.”

So, Hurt pivoted—he tried a major in Journalism with a concentration in Radio and Television Broadcasting. He stuck with it for several years, sure that he’d made the right choice and that this would be the path to fulfill his childhood dream. Hurt began interning for CBS Boston Channel 4, Channel 7, and WCVB-TV’s Channel 5.

Once again, he realized that he’d made a horrible mistake, this one of epic proportions. Each internship wrenched the wool further and further from his eyes. Hurt didn’t know where to turn. Television was a sham, and he wasn’t meant to be a news anchor. Beyond the screen’s glitz and glam, the types of news that the senior wanted to cover just weren’t there. He couldn’t resonate with a lack of substance.

“I did not want to get into television news because I thought it only told a part of our story, meaning the story of Black and Brown people in the communities that I came out of,” Hurt explained. “I felt like I needed more time and more space to tell longer stories that could contextualize the issues that we face.”

Directionless and gutted, Hurt walked into a class that would change his life forever: “History of Blacks in the Media and the Press.” Professor Elizabeth Hadley Friedberg challenged Hurt’s keen intellect. He and his classmates confronted the Black representations they’d consumed as viewers and readers of popular media.

“It really challenged me to think deeply about some of the images that I had normalized—Black people as being criminals, obsessed with sex, our women being sapphires and jezebels, and all of the negative stereotypes and tropes that have come to define much of Black people in the imagination of white people,” he said.

Friedberg had only just begun sowing seeds in Hurt’s mind. She showed Hurt the work of gay rights activist and documentary filmmaker Marlon Riggs. It transformed him. Hurt began questioning himself and his values. Riggs brought forth prejudices Hurt didn’t know he had. He carefully examined his Blackness and how gender and sexuality intersected within it. He fought to quash the bigotries his upbringing instilled in his mind. Riggs was his role model and savior.

“That’s what I wanted to do in life. I wanted to be like Marlon Riggs. I wanted to have the same impact on young people that Marlon Riggs had on me.”

Hurt wanted to be a documentary filmmaker. He rushed to speak with a professor in the department that did just that. They chatted for a long while, Hurt getting life and career advice. He asked the professor about filmmaking. He wanted to know the best way to portray a Black male perspective to the world. He wanted to tell what he knew best.

After watching several more of Riggs’ films, Hurt finally decided to make his own. It took six months of filming, editing, and interviewing. He traveled around campus and spoke to every Black graduating senior. He asked them to share their experiences, what it truly felt like to attend a predominantly white university in New England. At the end of his senior year, he packed as many people as he could into his college’s library and premiered his masterpiece: Moving Memories: The Black Senior Video Yearbook.

“People laughed, and they cried at something that I created. That experience was just amazing, ’cause it confirmed my instincts about the power of storytelling, and it also validated me as a budding filmmaker,” Hurt recalled.

After graduation, Hurt picked up a part-time job and became involved in Mentors in Violence Prevention (MVP). At the time, the group educated “boys and men about sexism and all forms of violence against girls and women.”

“Suddenly, it was like a light bulb went off in my head or something!” Hurt exclaimed. “What if I combined my ideas around race with my ideas around gender and made films that deconstructed both?!”

At this point in his story, Hurt nodded to an invisible beat, reliving his past euphoria.

The epiphany was the genesis of his professional career. He took five years to produce and gather funding for his film, I am a Man: Black Masculinity in America. He submitted the documentary to The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) and was promptly rejected. Though disheartened, Hurt didn’t give up; failure just made him “kick things up a notch.” He moved back to New York and “hooked up” with Primetime Emmy-winner Stanley Nelson.

Nelson closely mentored Hurt, navigating him through a film’s process. Hurt eventually struck out, taking an additional five years to produce Hip-Hop: Beyond Beats and Rhymes. The documentary explored representations of masculinity in rap and hip-hop culture. In pursuit of perfection, Hurt rewrote the film’s proposal over 26 times. On the 26th time, he stopped trying to appeal to the sensibilities of funders and television stations; he stayed true to himself. That proposal got his film shown nationally on PBS, at the Sundance Film Festival, and Aspire TV.

Despite his success, Hurt noted to the livestream’s viewers that the documentary film industry needed—and still needs—to change.

“Structural racism is in every industry, and that includes documentary filmmaking,” he said. “I’ve been very fortunate and blessed that every film that I have proposed to make, I’ve received funding to make, though less funding than my white counterparts. I also want to acknowledge the fact that as a man, a Black man, I get more opportunities than Black women documentary filmmakers. That’s something that has to change, and I do the best to amplify the voices of female documentary filmmakers of color who are talented, smart, and make really good top-notch films.”

“Finally, there is an issue within the documentary film world of white storytellers who get a lot of funding to tell Black stories. A lot of documentary filmmakers of color are now pushing back on that. Black people and people of color are the best positioned to tell unique stories about their respective communities.”

He smiled.

“That’s my story.”

In Closing: A Season Three Farewell

DuBois-Walton Spoke to viewers, New Haveners, and the country at large as she wound down the night. She and Kevin Walton said the series would return in the fall.

“We started storytellers to create a space where people could come together and through story, hear from each other, because that’s how we see each other’s humanity,” she said. “We connect to things that we see in common. We pause and notice things that we have different, but we ultimately see each other as people, and I think that is the spirit of racial equity work.”

She paused and began again.

“So, I hope that we’ll stay in a community. I hope that we’ll stay open to conversation, open to listening, and feedback. I hope we’ll each own that we all walk this world carrying bias and prejudice. The way we get free of it and not get limited by it is by acknowledging it; we can notice it when it pops up, and we can then have a wider range of responses to things.”

“Racism pops up in every aspect of society, so whatever it is, wherever it is, I hope we’ll enter it. Whether it’s staying engaged on issues relating to police brutality education, healthcare, or housing, I hope that we will look at each of those settings for including some and excluding others.”

Her gaze grew fiery, picking up steam.

“We’ll begin to notice those things and question and wonder why there’s not diversity in our friend circle, or why there’s not diversity in our neighborhood, or why there’s not diversity in the teachers that teach our kids, or any of those things. In noticing them, we then start to question and to challenge the system that is set up in that way and create space for some different ways of being. Goodbye, everyone, and thank you for joining us.”

You can sign up to tell your story next season by emailing here or sending a message here.