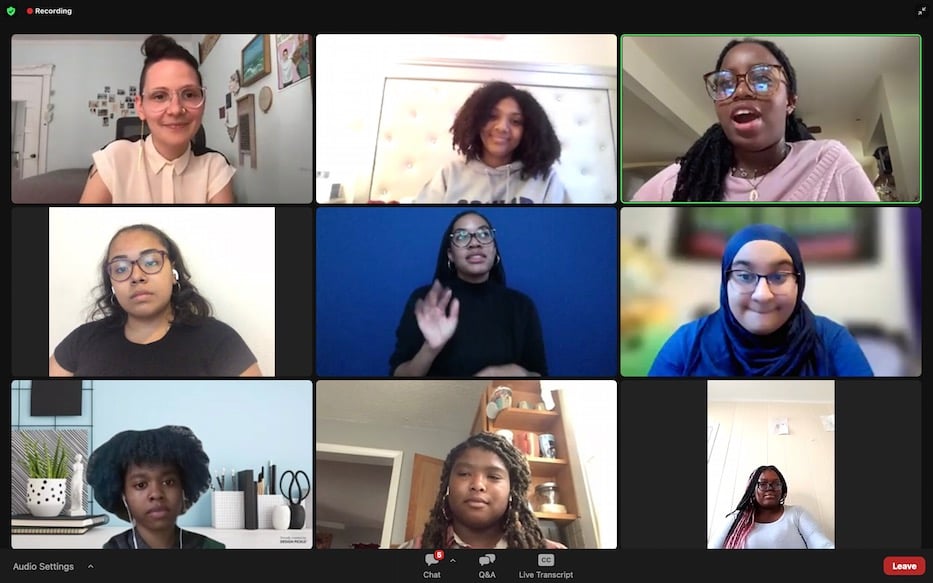

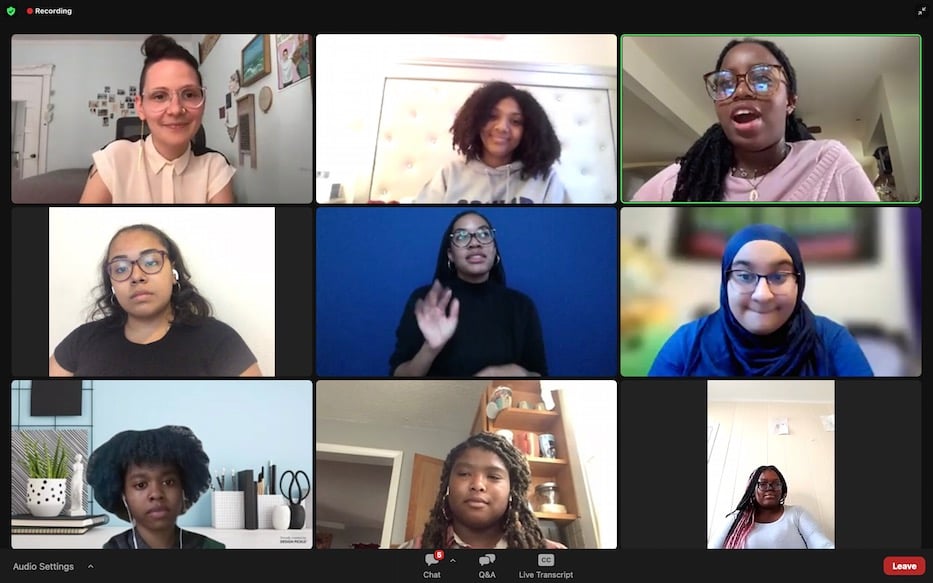

Screenshot from Zoom.

Student walk-outs and sit-ins. Peer-led petitions to get cops out of schools. Chances for young people to teach each other about empathy burnout—even as they risk going through it themselves. And the idea of student power, from the ground up.

Those were just some of the topics students covered Wednesday evening during “Youth Rising,” a virtual panel featuring students from Atlanta, Georgia, Winter Park, Flo., York, Penn., Detroit, Mich., Chicago Ill., and New Haven. Organized by the Zinn Education Project and Antiracist Teaching and Learning Collective, the panel drew dozens of attendees from across the country. It was co-moderated by Metropolitan Business Academy teacher Nataliya Braginsky and student Jayleen Nieves. Nieves was there representing Students for Educational Justice.

It was also an opportunity for the panelists to reflect on the phenomena of activist burnout, empathy fatigue, and a sense of feeling overwhelmed by the sheer number of issues their generation faces.

“These uprisings, we’re seeing them at Metro,” Braginsky said. At Metro, students have organized more walkouts this year than in the past eight years combined. “But it’s not just Metro, we’re seeing them around New Haven and throughout Connecticut and across the country.”

Across the hour-and-a-half event, youth organizers spoke about their advocacy work on issues as varied book bans, sexual violence, and school uniform policy. The common thread was all these issues take place within schools.

Two of the voices on screen were familiar ones: Amya Smith and Jaeana Bethea of Achievement First Amistad High School.

Last November, they and fellow members of the Amistad Social Justice Club organized a successful walkout addressing sexual violence occurring on school campus. Speaking to a crowd of mostly female students, Amistad senior Gabrielle Lopez addressed the multiple instances of sexual assault by a male teacher she survived during her sophomore year. Another student, Charity Reid, spoke about a male student who made lewd comments about and grabbed her body during her freshman year.

Bethea, who is a member of Citywide Youth Coalition as well as the president of Amistad’s Black Student Union, has been at the forefront of organizing against sexual violence at Amistad. She discussed the lack of avenues to report and receive responses to sexual violence. As highly visible organizers, she and Smith have become that much needed avenue. But the emotional weight has been massive.

“It’s really baffling how much Amya and I get stopped in the hallway by staff members and students with any concerns,” Bethea said. “Like something just happened with a teacher and they come to us. It’s almost like we don’t have a principal. It’s so sick.”

The emotional burden of receiving students’ stories of sexual violence has taken a toll on Bethea’s mental health. One of her biggest challenges is not internalizing the heavy and complex emotions that are shared with her, she said.

During the stages of the pandemic, the emotional toll of Bethea’s activism increased. During online school, Bethea was continually receiving with news of the anti-racist struggles unfolding across the United States. Sitting at home in her bedroom, she lacked peers to process her emotions with. She remembered sobbing alone in bed.

Now that school is back in-person, Bethea finds herself weighing two conflicting options: go to class and earn the credits she needs to graduate, or skip class and undertake the advocacy so necessary to the lives of her peers.

Smith, who is the president of the Amistad Social Justice Club, said she shares the same exhaustion. Her advocacy work takes her beyond meetings with administrators and school board member to the offices of social workers, where she reports instances of sexual harassment or violence, she said. It’s a lot for a “young girl” like her, she said.

I love what I do, but I hope that I don’t have to do this for the rest of my life,” Smith said, her tone of voice expressing her frustration and fatigue. “We should have an expiration date. This is one of those careers that absolutely should become obsolete within the next generation.”

“I’d do anything to be a regular high school student,” she later added.

Student activists across the United States are experiencing that same sense of burnout Two hundred and fifty miles away in Pennsylvania, Christina Ellis and Edha Gupta of the Central York School District organized a series of protests in opposition to a district-wide ban of a list of books and anti-racist educational material. After a nine-month organizing effort from Central York students, the district voted to temporarily lift the ban.

For Ellis, advocating for a curriculum that acknowledged her realities as a Black young woman was an absolute necessity. But the time and effort it required of her was monumental.

In addition to activism, she works a job, participates in theater, and is juggling all the responsibilities and activities of senior year of high school.

“It’s my senior year, and like a lot of things are happening on top of this,” Ellis said. “Activism is something you don’t turn off.”

Still, the students across the panel echoed that they are grateful for the lessons they have learned.

“I love this. I love what I do as a student activist,” Ellis said.