LGBTQ | Music | Arts & Culture | Theater | Black Lives Matter | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism

| YouTube. |

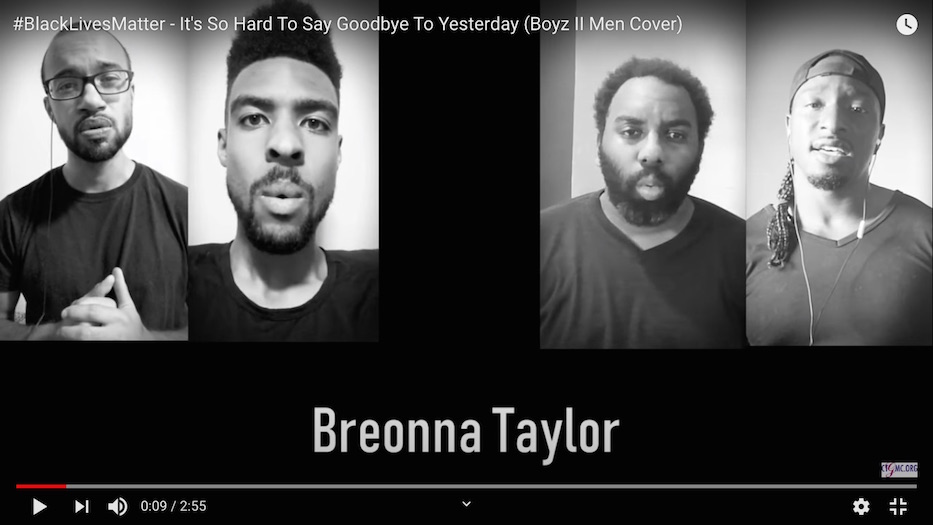

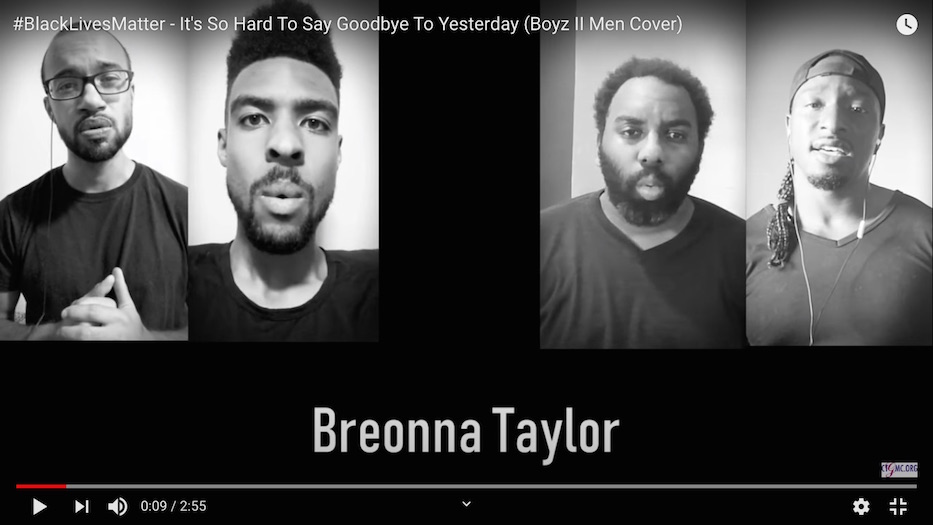

The faces fill the screen, a single blank black space hanging open in the middle. The faces take a breath in; they look out at the viewer. At seven seconds—just as Cecil Carter lifts the melody for the first time—Breonna Taylor’s name appears. The space begins to ache, an absence that is palpable even beyond the screen.

Carter looses a sparrow from his chest. The names roll on: George Floyd, Atatania Jefferson, Aura Rosser, Stephon Clark. His voice lifts: “I thought we’d get to see forever/But forever's gone away.” Botham Jean. Philando Castile. Alton Sterling. “It's so hard to say goodbye to yesterday.”

The video comes from James Hampton, Aaron Scott, Marcus Tart, and Carter, all members of the Connecticut Gay Men’s Chorus who are adding their voices to the Black Lives Matter movement. Last week, the four released an emotional plea to say the names of those lost at the hands of law enforcement. The piece is an a cappella cover of Freddie Perrin’s “It’s So Hard To Say Goodbye to Yesterday,” popularized by Boyz II Men in 1991.

“To the Black community, we love you,” they wrote in a note accompanying the video. “ We wanted to use our talent and our voices to keep the message of the protests alive and to remind everyone of the ones we've lost and the reason we continue to march. Say their names."

The idea for the video began in late May, after the state-sanctioned murder of George Floyd fell just six days before Pride Month, and in the third month of COVID-19 quarantine. Around the choir, the parallel pandemics of COVID-19 and structural, anti-Black racism were raging. Within the choir, members were supposed to be working on a bouncy version of “All You Need Is Love.” For several members of the group. it felt tone deaf.

“Having COVID and the murder of George Floyd coincide with Pride Week was such an extreme sense of emotions,” Hampton said. “You have Pride, which up until this point in time has been more of a celebration. And you had that against the backdrop of the apparent racism that was being uncovered, the angst and the anger and the resistance."

"It was so weird for me to be like ‘Oh, it’s June. Let’s celebrate,’" he continued. "Or seeing people happy that it’s Pride. But you’re like, I don’t feel prideful. I don’t feel happy. I don’t feel like I want to celebrate. What progress have we made?”

Tart, who has been a member of the choir for a number of years, thought about the Boys II Men cover, which the four originally performed two years ago at a concert dedicated to boy bands. Back then, they were able to stand on a stage and hold hands as they sang. Now, they were in their homes, unable to connect with each other without the presence of technology. When it seemed like they needed to gather most, it was out of the question.

“I felt really helpless,” Tart said. “It felt like a pattern. I felt like I was living something over again. I was getting flashbacks of Eric Garner and was like: How did we end up here again? I already had a sense of: We have to do better. We have to go out there and do stuff. I’d been pushing myself to go out there and be a part of the change I wanted to see in the world.”

Tart worried about his own mental health. He was mentally exhausted, and thinking about his family and friends. After he proposed bringing back the song as a video, Hampton jumped in to organize the process. He pulled the four together in a brainstorming session on Zoom and started taking notes.

“I wanted it to be a total democracy,” he said. “This is a message from all of us. There’s a difference between producing a tribute and producing something just to ride on the coattails of a movement. And I did not want this to be commercialized. I did not want this to be about us. This was more about the message.” ”

He listened as members weighed in on everything from color scheme—the video is in greyscale—to the list of names that would be presented. In a list that spanned five years, he recalled having the gut-churning realization that not all of them could fit in a three-minute video, because so many lives had been taken prematurely. Tart added that there was an added cruelty: the list continued to grow as they worked on the video.

| Carter during a rehearsal in May 2019. The CTGMC celebrated the 50th anniversary of Stonewall in its concert last year. Lucy Gellman File Photo. |

Carter insisted that Breonna Taylor’s name appear first. Taylor was an award-winning, 26-year-old EMT who was murdered by police this spring, when they burst into her home as she slept. She wanted to use her skills in emergency medicine to become a nurse. On what would have been her 27th birthday, protesters around the world sang to her memory. Her killers remain free; four months after her family buried her they are still sleeping in their beds.

“Her story is just so sad,” he said. “You’re in your own home. The officers that gunned you down, they’re still free. There’s no justice. I understand that we saw the video of George Floyd. I’m not detracting from George Floyd. I just wish this started with her. This should have started with her. This anger within people.”

In the video, the four vocalists capture all of that. As they appear in the frame, each looks right at the viewer, then plunges almost immediately into the song. Scott pushes his face close enough to the camera for the viewer to notice when his eyes close as Botham Jean’s name appears at the bottom of the frame.

At the far right, Carter carries the melody, his voice a rising tide. The others are small, cresting waves beneath him, carrying him towards a distant shore. The lyrics come from somewhere deep inside his chest.

And if we get to see tomorrow

I hope it's worth all the wait

The names roll at the bottom, one after the other in large white text. For every name that has been called out at a protest, there are many that have not: Aura Rosser, the 40-year-old Michigan woman shot inside her home in Ann Arbor in 2014. Michelle Cusseaux, who was shot and killed by police in her Phoenix apartment just weeks after Michael Brown was murdered in Ferguson, Missouri.

28-year-old Brooklynite Akai Gurley, murdered in the unlit stairwell of his building when an officer’s bullet ricocheted off the wall and into his chest. Twenty-year-old Charlotte resident Janisha Fonville, a queer Black woman who was killed by an officer in her home in 2015. It was his second fatality and third shooting of an unarmed Black city resident in five years on the force.

The names keep rolling. The message is clear: the list is already too long. It is up to listeners to grieve—and also to do everything in their power not to allow it to grow longer.

| Aaron Scott, with AJ Ganaros and Marcus Tart, rehearsing for a performance in February 2019. Lucy Gellman File Photo. |

“During it, I felt as if it wasn’t enough,” Carter said. “I wish I could have done more. You doubt … am I giving enough emotions? Am I giving enough to give these people justice, or represent these people in the right way? I just want people to understand that I feel your pain.”

For some of the members, recording and producing the video was also part of a healing process. The choir has not gathered in person to sing since March; its spring concert was cancelled months ago, and all Pride performances took place virtually this year. The most social interaction that some of the members have takes place in Tuesday night Zoom meetings.

Scott recalled the experience of being by himself in his own home, and singing alongside a track of chorus members. At the time, it felt awkward to be alone, and have his friends and fellow musicians bursting into song on an electronic device beside him. Now he’s grateful for it.

“Just thinking about that is like, whew, wait a minute,” he said. “It was really powerful when I look back on it. You have to put the message before the production. And of course you want to sound good, but don’t want to take away from what you’re trying to say, what you’re trying to do. It was hard to maintain that composure.”

Hampton said that he didn’t think about the impact of the video, which he streamlined and produced using his phone, until after he had finished the technical side of it. Then he watched what he had made.

“This keeps the message alive for at least one more week,” he said. “It pushes us down the line to continue talking about it. And not just talking about it in a ‘Oh, someone burnt something down.’ Talking about it like, ‘There’s something that needs to be fixed.’ Remember people that we lost. This is why we are protesting.”

“While I’m still worried, and still anxious and scared, I don’t feel paralyzed,” Tart chimed in. “I feel like there’s momentum. I feel like working on this project has built momentum.”

Joining A Larger Chorus

The video is one of several musical and artistic projects in New Haven addressing the ongoing epidemic of police brutality, and particularly anti-Black police violence. In early June, a number of musicians released new work expressing solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement.

At the end of June, Middletown-based The Lost Tribe released “Say Their Names,” an anthem in both English and Wolof that memorializes including George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, Tayvon Martin, Tamir Rice,Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Philando Castile, Sandra Bland, Ahmaud Arbery, Lavante Biggs, and others. Wolof is spoken in Senegal.

Sou akk ak yelief amoul djame dou am, members of the ensemble repeat in perfect, echoing time. No justice, no peace. Flute unfurls around them.

There is a specificity to the track: drums and guitar rumble under I-Shea (Iréne Shaikly) as she repeats name after name, each a prayer that has gone unsaid for too long. She is careful and deliberate, as if she is feeling the weight of each in her mouth before she repeats it for the world. Under her, the beat loosens and stretches out, a sort of orchestrated heartbeat.

There is a reminder here, a call to memory and also to action. By the end, the song sounds like it was made for a march, slowly walking forward in the streets.

At the beginning of July, Long Wharf Theatre also released its first commissioned work from UNIVERSES, the New York-based ensemble run by Steven Sapp and Mildred Ruiz-Sapp. Titled Sing Their Names, the piece fuses propulsive audio, video collage, poetry and spoken word to deliver a moving tribute to lives lost to police violence.

The theater also received $20,000 from the National Endowment for the Arts earlier this summer to workshop the ensemble’s new musical, Maria.

“Sing Their Names begins the collective’s years-long commitment to commission and develop new plays that represent the kaleidoscope of the human experience, building a new American theatre repertoire that vigorously includes the voices of artists of color," read a statement released with the video.

To listen to The Lost Tribe's "Say Their Names," click on the embedded player below.