Music | Black Lives Matter | COVID-19

| Fernanda Franco at a concert at Cafe Nine last year. Lucy Gellman File Photo. |

The beginning of the track is mellow, polite almost. A listener can feel themselves sinking into the strings, letting their shoulders unlock and sway a little. Fernanda Franco’s vocals, etched with mourning, come soaring in.

“It's such a shame,” she half-croons, half-wails. “I don't know your name/But I see you fight/In the desperate night.”

Franco’s "Shame" is one of several new tracks, videos and virtual performances that have come from New Haven musicians in the past two weeks, in support of the Black Lives Matter movement, intersectional coalition building, and dismantling white supremacy. The messages hit close to home: there have been 21 fatal officer-involved shootings in Connecticut in the last five years, including seven that have taken place in the past year alone.

They join a growing chorus of artists decrying the state-sanctioned murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade and hundreds of others whose lives have been taken by law enforcement. Some have also responded to the specific and sustained anti-Black, anti-Indigenous racism in the fine and performing arts.

On a Sunday afternoon at the end of May—just as protesters were walking onto I-95—David Chevan and Warren Byrd of the Afro-Semitic Experience released a recording of “We Shall Overcome” in honor of Floyd’s life and legacy. While the number was initially set to be recorded as an ensemble piece this spring, COVID-19 meant that Chevan and Byrd recorded from their respective homes.

Chevan, who mastered the track, said it harkens back to the piano-bass duos that he and Byrd did at the beginning of their collaboration, which started in the 1990s. The two chose the song because of its long history as an anthem geared towards both justice and coalition building.

But it’s a callback in more ways than one: the message is still as relevant and stinging as it was two decades ago. On the same day that he released the video, Chevan and his wife Julie joined 1,000 protesters downtown in a march led by Black Lives Matter New Haven. He recalled feeling several of the same emotions that he felt in the early 2000s, when he and Byrd started by performing in churches and synagogues.

“For over 20 years, we’ve been telling people that the era of Civil Rights isn't something in the past,” he said in a recent phone call. “It’s ongoing. With some of the police killings that have happened over the past decade, our message of unity and community is really true.”

Both he and Byrd suggested that if the song is a rallying cry, it also serves a specific healing purpose. Byrd recalled growing up in Hartford’s housing projects decades ago, watching many of the same patterns of police brutality that are still unfolding today. An officer would roll up in his car, arrest someone from the neighborhood, and then that person would be gone.

“I think music touches something deep inside of us that goes beyond the language we've created in words,” Byrd said in a recent phone call from Amsterdam, where he and his wife are spending a few months. “It begins to heal things. It's a way I've worked on my best self and a way I've worked on my worst parts. When you understand what that is, you can understand how to bridge those gaps.”

“I have a sense of hope in that people are responding in a very loud way,” he said. “But I would love to see a remedy to this. I have no sense of what that looks like, but I do have a vision of what that could be. First of all, we need to come to terms with the fact that we're all humans. We have to respond to what is dark as well as what is light. I think if everybody can come to some kind of ability to strengthen their frontal lobe, we could have that.”

That final weekend of May, musician and wellness coach Jessy Griz also added her voice to the conversation, with a professional recording of her song “Our Battle.” Griz first wrote the song in August 2014, as she watched the news of 18-year-old Michael Brown, shot and killed by Officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri. A grand jury later chose not to indict Wilson for gunning down an unarmed Black teenager in the middle of a city street.

“I remember watching the news on my laptop and sitting on the couch thinking, what's it gonna take, white people?” said Griz, who is white. “Is it going to take another child?”

She started writing, doing work to undo the world as she understood it when she wasn’t developing the song. As she watched the murders of unarmed Black men and women unfold across the country and the state, it became an anthem that felt painful and necessary to her: she first recorded it in 2016, then performed it last year at a benefit concert for Stephanie Washington and Paul Witherspoon III after an officer-involved shooting in New Haven.

In the song, she calls for listeners—particularly her white peers—to undo their own racism for the survival and basic humanity of people of color and themselves. With its hook, it becomes a call to arms and a sort of prayer: there are whispers of Luke Nephew’s “Brother/I can’t breathe,” and Reverend Sekou’s parallel “Neighbor,” of sermons usually reserved for Sunday worship, and Assata Shakur’s reminder that white supremacy wounds not just people of color, but also white people.

“We will not not wait/for one more cry/one more voice that has been silenced/hear him pleading for his life,” she wails, “For us to stop saying one life is less than another/that’s my brother/that’s your brother/that’s your brother.”

It’s an appeal for collective action—the community before the individual, the melting pot that actually learns how to melt this time. But something else has changed in the recording: polite, guitar-strumming Jessie of 2016 is gone.

Her vocals simmer and spill over; her fury is righteous. When she sat down to record at The State House in late May, a birthday gift for the photographer Joel Callaway, the piano and mic caught all of it. With the video, she included a list of anti-racism resources.

“It was hard this time,” she said. “I think the first time I was just heartbroken and pleading, and this time I was just just angry. I think this time, the white conversation is wider than before. I'm going deeper in my own unpacking of my own biases and prejudices. I think that if I see a revolution in myself, as someone who saw themselves as an ally, then the revolution for people who didn't consider themselves allies could be real.”

Other artists have recorded in their homes, used music as an educational platform, and brought those messages straight to the streets. Franco, who is the frontwoman to the band FaTE (Fernanda and The Ephemeral), recorded “Shame” last week, as she started writing and found she could not put down her pen.

As she wrote, the song became a reflection on her own experience as an immigrant and Afro-Brazilian. Growing up in Bethel, Franco was one of three Brown people in her class. Teachers used to confuse her with the other two students. At the time, she said, she let it roll off.

Now, she’s been thinking about what those microaggressions meant—and how her sister carried the pain of that experience differently. After releasing a bare-bones track last week, she invited musicians to submit tracks for a reboot of the song.

It is one of five new pieces she is planning to release in the next weeks, all of them influenced by the current moment. One, titled “More,” is dedicated to her eight-year-old son. Franco added that all of the proceeds from “Shame”—the song is free, but people have been buying it anyway—will go to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and the band will match it.

“The goal is to bring people together through music,” she said. “I just have this resentment of blocking people from sharing their emotions. I have so many white allies that feel like they can’t share, and we're not doing it together. And the truth is, that we can't move forward until we all hold hands and walk together.”

| Castillo: Feel the music. |

On the first Friday of June, Addys Castillo and members of Movimiento Cultural Afro-Continental (MCAC) educated thousands in the history and echoing, pulsing footprint of Bomba as an art of resistance. Before she herself moved to the drum—and invited in rally-goers to do the same—she described the importance of both rebelling and healing through the process.

“Every single one of our cultures had a drum,” she said, before a weekend that took her to dance Bomba at protests, rallies and marches across the state. “It’s like a heartbeat. It’s a heartbeat. All of us got a drum. So I want you to listen … and understand that this music, it’s not R&B. It’s not about who has got the nicest voice. This is about who feels the music.”

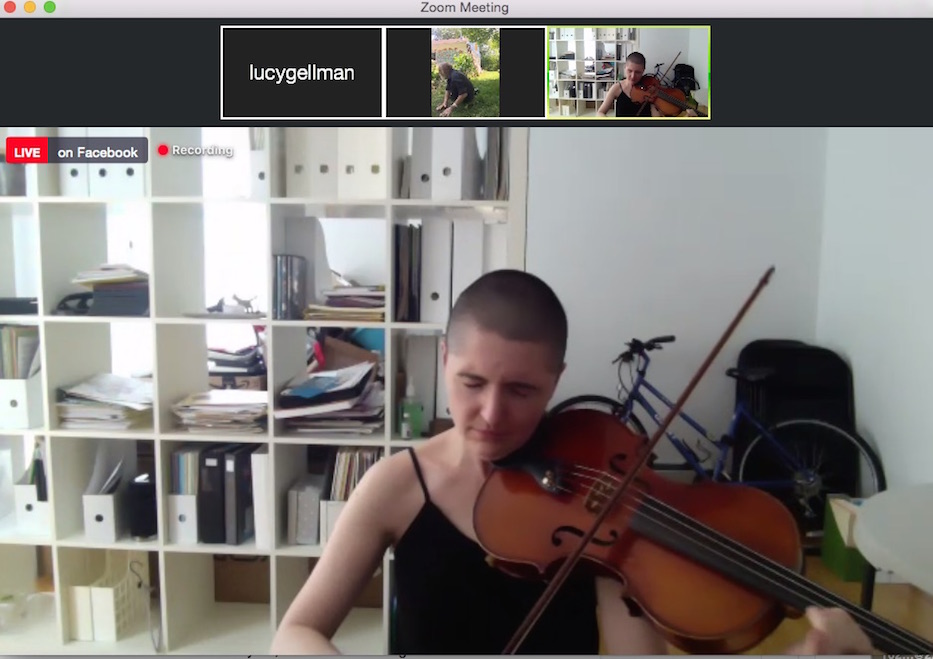

Some have been quieter, and even elegiac. On Tuesday, musician Bethany Wilder powered up Zoom an hour before George’s Floyd’s memorial service was scheduled to take place in Houston, Tex., picked up her viola and began to play. She explained that for years, she had justified keeping her distance from the news as a way of protecting her own mental health.

But then she realized “what a bubble I've been in for all this time,” she said. In the past days, she’s dug into conversations, from confronting the news to taking on the colonialism "endemic to classical music," from its heroes down to its very terminology. To the screen, she announced that she would be playing the prelude to J.S. Bach’s Cello Suite No. 2 in D minor.

“You will hear how this music questions, and pleads, and reaches a point of breathlessness and something beyond,” she said.

And it did, an ebb and flow that wound its way upward, frantic and exhausted by the end. In addition to Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor, Wilder dedicated part of the concert to remembering 18-year-old Mouhamed Cisse, a cellist who was shot and killed last weekend in Philadelphia.

In a time of isolation, she said, she was hopeful that the music could help heal—and spark conversation that needed to happen both in and beyond the music community.

“I send you hugs, courage, wishes for difficult things,” she said. “Instead of being afraid, let's open our minds and our hearts even wider, so that Instead of fear there is love.”

Listen to Fernanda Franco's "Shame" here.