Culture & Community | International Festival of Arts & Ideas | Arts & Culture | COVID-19

| YouTube. |

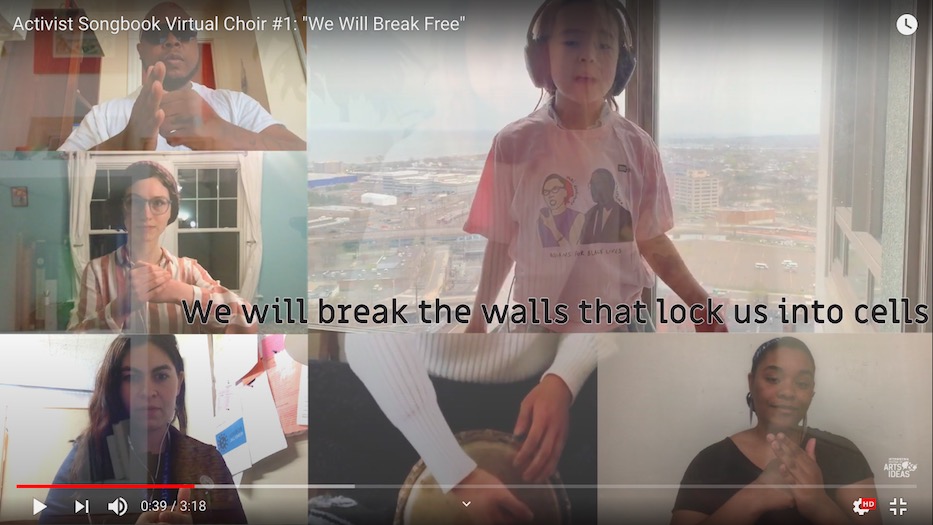

The drum plays in the song, slow and steady as two forward marching feet. A young child appears, brown and chrome rooftops of the city sprawling behind her. As she begins to sing, the frame fills with small boxes, each of a musician clapping their hands. They pause on every fourth beat to form a fist. The lyrics flow.

“A body isn’t made for a jail or a box/A body will defy all the fences, all the locks,” the child sings, and more hands clap right on cue. “We will break the walls that lock us into cells/We will break the laws that keep us from ourselves.”

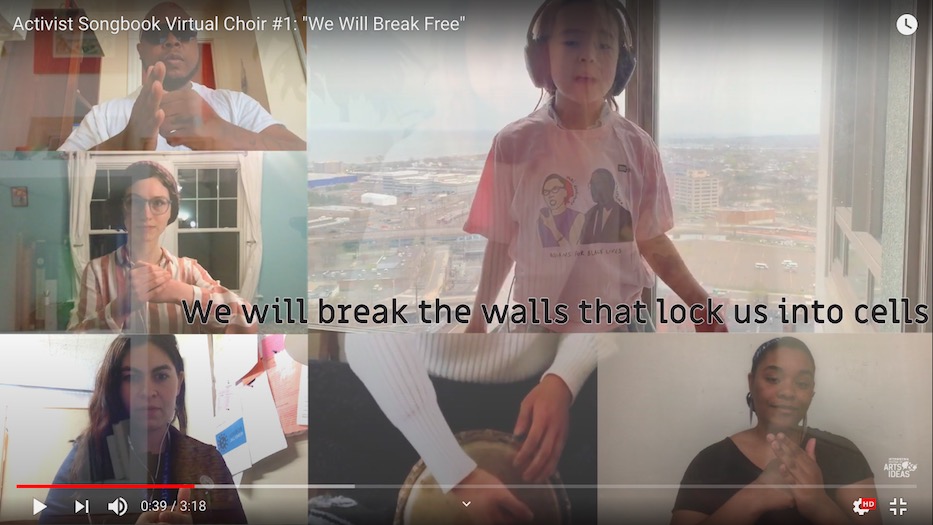

“We Will Break Free” is the latest song featured in the Activist Songbook, an evolving project from activist-artists Byron Au Yong and Aaron Jafferis and organizers in the Bay Area, Philadelphia, and most recently New Haven. Tuesday night, the two joined artists Melissa Li, Kit Yan, and Paul Bryant Hudson for “Songwriting as Radical Imagination,” the first ideas event in the 25th annual International Festival of Arts & Ideas.

Li and Yan are the creators of Interstate, a musical based on their experiences as queer Asian-American artists and activists. Hudson is a local musician and one of the founding members of At Home in New Haven. This year, the ideas portion of the festival is dedicated to “Democracy: We the People." A full listing of programming, which is fully virtual and begins this month, is available at the festival’s website. Over 35 attended Tuesday’s talk, which was broadcast on both the festival’s website and on Facebook live.

“I am interested in the ways in which we are currently in these little boxes, right here, on this screen, and in these bigger boxes in some ways,” said Jafferis at the top of the hour. “In the places where we’re staying, separated from each other. And the ways in which actually right now, in this moment, radical imagination is like a survival necessity … in order for us to exist outside of these little boxes that we spend so much of our lives in now.”

Started in 2018, Activist Songbook is a growing collection of 53 original poems, chants, songs and raps all dedicated to social justice and collective freedom. The project was partially inspired to honor the legacy of Vincent Chin, whose 1982 murder in Michigan spurred stronger hate crime legislation across the country. It is also inspired by Grace Lee Boggs, an organizer and activist in Detroit who urged community members to use self-transformation as a way to change their neighborhoods.

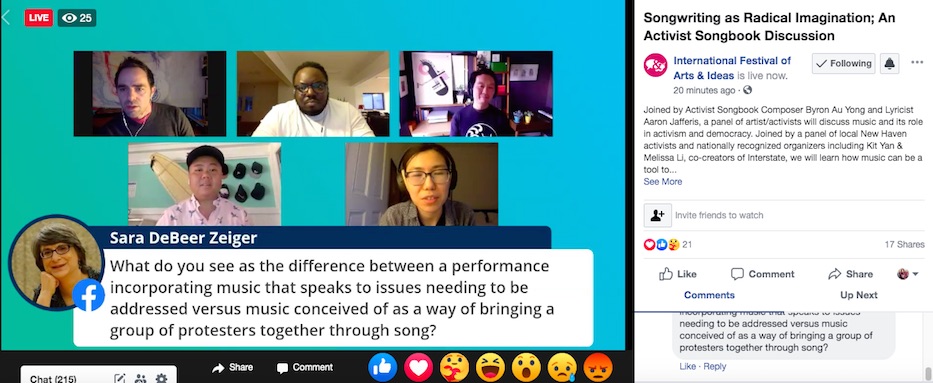

Over two years—and multiple workshops—the Activist Songbook project has grown to include pieces in multiple languages, from anthems opposing bullying to a sort of songified Know Your Rights training. As it comes to New Haven, the festival is supporting a virtual choir and series of online workshops. The group is also working with Octopus Theatricals and several members of the local activist community.

“We Will Break Free,” for instance, is dedicated to ending the carceral state not just in Connecticut, but across the country. It is inspired by Susan Hayase, Tom Izu, Masaru Edmund Nakawatase, and Mike Ishii—all Asian-American activists and survivors of xenophobic American policies whose historical work is often overlooked or not taught at all.

When the two were first writing the songbook, Jafferis worked directly with Jeannia Fu, a community organizer with the Connecticut Bail Fund, to understand the difference between prison abolition and criminal justice reform. He recalled that he wasn't originally completely onboard with the gospel of abolition. Then the opened his ears.

“Literally in the process of writing this song based on her interview, it transformed me,” he said. “It transformed my relationship to the idea of abolition … the creator, and the singer, and the performer—that feels like the most fundamental places where this radical imagination can happen.”

| Clockwise from top: Aaron Jafferis, Paul Bryant Hudson, Byron Au Yong, Melissa Li, and Kit Yan. Facebook screengrab. |

The song feels both right on time and long overdue. While calls for prison abolition are not new, they have taken on a new urgency in the past two months, as prisons and detention facilities become potential hotspots for COVID-19. At the Cook County Jail in Chicago, for instance, over 400 detainees and 300 staff members have tested positive for COVID-19 since March.

By last month, almost 250 detainees in Connecticut prisons and jails had tested positive for the virus. More than once, detainees with COVID-19 symptoms have been sent to solitary confinement instead of given medical aid. Listening to the song—which is accompanied by a video of New Haven artists, activists, disability rights fighters, students, and musicians all singing together, is a galvanizing wake-up call. It’s an accessible one too.

That is exactly what activist songwriting is supposed to do, suggested members of Tuesday’s discussion. Now a musician and organizer himself, Hudson grew up with his great-grandmother, a musician and writer who was born and raised in New Haven over a century ago. Her creative work, and that of those around her, became “the lens of expression” through which he saw the world.

“I don’t know the limits of songwriting,” he said. “I don’t know if there’s anything a song can’t do or contribute to at the very least. Like, there are properties to experiences rooted in liberation that help folks metabolize experiences, and traumatic experiences especially.”

He brings that approach not just to his own work, but to his experience as an activist, a New Havener, and a listener. He praised anthems from Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” to Harriet’s contemporary “Heal and Chill,” the latter of which advocates for rest as a means of self-care.

“There’s this really meaningful link that songwriting creates between your inner being and the world that otherwise wouldn’t exist,” he said. “I mean this for the folks who write the songs, and maybe even more so for the folks who experience the songs.”

Li recalled the impact songwriting has had on her own life and work. Decades ago, she began writing in her early teens, around the same time she was coming out. Initially, she said, the songs were “bad … really bad,” infused with the same righteous anger as the Ani DiFranco music to which she was listening. But the longer she wrote, the more the lyrics fell into place.

“I started writing about capitalism,” she recalled. “I started writing about racism, and just a lot of issues that were affecting me. Homophobia, all of that. Just throughout my teens. And [it] really cemented the artist that I was and wanted to be.”

Now, she and Yan are part of the team behind Interstate, a semi-autobiographical musical that follows two queer, Asian-American artists as they tour the country and collaborate with several artists, activists and organizers along the way. During the discussion, Li performed a song from the musical about a character named Henry, a transgender teen in Kentucky whose mother discovers him taking testosterone and begs him not to let his father know.

“There is something about song where it just, it lives inside you,” she said. “It’s something that everyone can do. When you sing a song, when you hear a song, you can absorb it.”

Yan, who spent a decade as a professional slam poet, added that the very DNA of songwriting can be intertwined with activism when it is at its best. Over a decade ago, they and Li were members of the band Good Asian Drivers, out of which the musical was born.

They added that that may be particularly true now, as the realities of physical distancing come up against the machinations of xenophobia, anti-Asian and Asian American hate crimes, and anti-Black racism. They echoed Hudson, who had exhorted the importance of songwriting as a tool for both social justice and rest and resetting.

“I’ve always felt that the personal is very political for us as queer and transgender artists,” they said. “Sometimes … we’re just processing and writing about, like, our feelings and emotions. And then sometimes it lives in a story where we sort of fictionalize and combine a bunch of moments together in order to think about the connective tissue between some of these moments.”

“I really think our work is only possible in conversation with other mediums and like activist work, academic work, and political work going on out there,” they later added. “In isolation, we’re not really doing much. But as a community, there are lots of people doing this work. A piece of art, or a song or a musical or a play is one small part of that big change.”

Together, panelists suggested, those elements have the power to move people towards collective action, towards validation, and towards something that might approximate democracy in a country where it has always been an idea under siege. Au Yong recalled that in the days following the September 11, 2001 attacks, he tried to find groups that were singing together.

He found a clip of Congress attempting to sing in unison—badly—and recalled thinking “oh, maybe this is why politics is failing.” But then he discovered an interfaith church where a friend was singing. Members of the community joined in. As the song moved through the artist’s body, everything started to feel like it might be okay.

“There was a power, and there was a feeling of groundedness, and a feeling of ‘yeah, we’re gonna get through this,’” he said. “Because we have voices, and we can move our bodies, and we can recenter ourselves. It’s only when it’s missing that it’s a problem.”

As they reached the end of the discussion, Hudson, Li and Yan also reminded attendees that the idea of protest music isn’t a new one. Some people just haven’t always been listening. While the technology may be changing—Li joked that she is too old for TikTok, but has been keeping an eye on it—there’s a long legacy there. And it’s still evolving.

“I think that our communities, communities of color, queer folks, trans folks, women, marginalized folks—there isn’t a new movement for us,” said Yan. “We have always been here. And we have always been making art about ourselves, and our communities, and our families, and our feelings. And our rights.”

To find out more about Activist Songbook, visit the festival's website or email activistsongbook@gmail.com.