A Broken Umbrella Theatre Company | Arts & Culture | Theater | COVID-19

| A Broken Umbrella Theatre Photos. |

“Before there were words, we drew not breath, but pictures.”

The building’s doors were an entrance to a world unfettered by space and time.

“Before there were books, there were pages.”

Yellowed strips of paper fell from a domed ceiling onto the crowd below. A little girl in the audience gasped—heralded by low hoots, origami owls pulled their puppeteers down a set of spiral staircases. Stoic ushers stood at attention. Ambient music began to play.

Last week, A Broken Umbrella Theatre premiered a YouTube livestream of its 2012 The Library Project for virtual audiences. The performance was designed to celebrate and take viewers “inside” the New Haven Free Public Library even as its doors remain closed.

Since its founding in 2008, the 39-person ensemble has traveled across greater New Haven for its site-specific, historical productions. In 2012, the company initially performed The Library Project at the downtown Ives branch. At the time, it commemorated the 125th anniversary of the New Haven Free Public Library system.

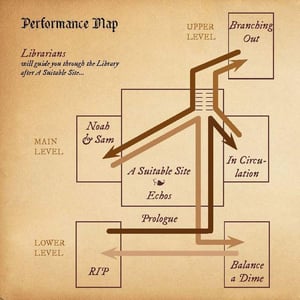

The work consisted of nine, 10-minute shows dispersed throughout the building. Audience members were able to choose the sequence in which they watched each performance in a guided walkthrough. Though library administration commissioned the production, it was cast members who ultimately felt compelled to represent the rich history of an institution that had given so much to the community.

“The library has always been an escape, a home, an oasis,” said Rachel Alderman, a founding member of the group and an artistic associate at Hartford Stage. “Some of my earliest memories are of going to my hometown library. I can still picture, to this day, where the Beverly Cleary books were kept and how proud I felt when I could write my name to get my first library card. It meant access to so many stories, lives, pictures, and ideas.”

The Library Project’s livestream granted that access to viewers. The stream amassed 346 views. A Broken Umbrella Theatre had returned a cultural institution to its people.

Behind the scenes, the path to the online premiere was an arduous one. Normally, A Broken Umbrella Theatre hinges on location and physical proximity. Its members are scattered across Connecticut in disparate living and working conditions,; many are no longer able to volunteer their time to the group. As performance venues shut down and physical gathering became untenable, production also halted on a piece about American Football creator Walter Camp.

“We don’t want to lose momentum, but COVID has changed everything going forward for everyone,” Alderman said. What does it mean when you’re working on a show about physical contact, and suddenly, you can’t have physical contact with anyone? There’s a lot of layers to this for us in terms of our creation process.”

Those trials have not suppressed the creatives’ ingenuity. Instead, cast members have converted productions to online platforms. Their first attempt was a performance by The Regicides, a comedy improv troupe affiliated with the ensemble. The group gave a virtual performance titled “We’re Trying Something” for the Westville Village ArtWalk in early May. It was a multimedia piece composed of prerecorded bits and socially distanced interactions.

Virtual audiences were delighted. The show’s success prompted A Broken Umbrella Theatre to push forward. Artistic Director Ian Alderman and New Haven-based videographer Nicki Chavoya collaborated to bring The Library Project to the web. The show’s “Choose-your-own-adventure-esque” quality made traditional archival an impossibility. Through trial and error, the two edited residual 2012 footage into a virtual walkthrough, retaining the experience’s first immersion.

“It was the kind of thing where we realized that we were in a bizarre and unique position to let people back into a cultural institution, their community center, to bring it into their homes since they can’t go into it right now,” Alderman said. “Not being able to go to the library makes me want to visit it more. All of a sudden, I start missing things about the library that I never even usually take advantage of when I’m rushing through my daily life”

“In this quiet, shelter-in-place moment, certain cravings surface—things I wish I could do, places I want to go,” she added. “I have yet to try out the Maker Space at the Ives Branch, for example. My 3-year-old hasn’t been to the children’s section of the Mitchell Branch in forever and hasn’t built a deep connection to those rooms and our amazing librarians yet. Now, more than ever, I want him to feel at home there.”

Alderman watched the livestream with one of her young sons. His youthful eyes witnessed the spirit of an artist, bemoaning his murals in the memorial library’s lower stacks. He beheld an effervescent dance, “In Circulation,” watching women twirl and leap around the room with books in hand. There was an imagined meeting between Noah Webster and Noah Morse in the Local History Room, an argumentative commentary on the evolution of language—a meeting of friends after a wife’s death.

He observed two little girls and their older sister read the leaves of a paper mâché tree. The sequence was called “Branching Out,” the section of the show his mother had conceived so long ago.

“A good book has no ending—RD Cummings,” Kaatje Welsh, the smallest sister, ran to the left. Her curls flew aloft in all directions.

She was six at the time. She attends high school now.

Remsen Welsh leaped towards the right. “My first memory of a library? —walking to my local library for the Nancy Drew mystery series—Angela, age unknown.”

She was 10, small and spry with a mischievous grin. She’s now a freshman at Oberlin College.

The oldest stood, rustic guitar strapped to her back. “My first and favorite memory of the Stetson Library is sitting in the nook to the right of the stack, listening to stories being read by the librarian—Anonymous.”

She was sixteen and soft-spoken. She dedicates her adult life to music and massage therapy.

Alderman and her son watched. The branches and leaves of the paper mâché tree connected hundreds of stories across space and time. Alderman was pregnant with her oldest when she worked with the girls that read the artificial plant—life’s branches were surreal. Alderman felt her “life journey shift into perspective.”

“Finding ways to connect during this pandemic is the key thing here,” Alderman said. “People need to come together throughout this experience in whatever ways they can. You can’t underestimate the power and the importance of what cultural institutions bring to a community and what it means to gather together."

"Here, we’re gathering together for a theater performance,” she took a breath, “all in one space, breathing as one.”