Carroll Brown, longtime organizer of the event, ushers in a moment of silence as attendees listen to the "I Have A Dream" speech. Lucy Gellman Photos.

At West Haven’s First Congregational Church, a Sunday afternoon hush was falling over the crowd. Speakers crackled to life. Deep and steady, the voice of the late Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. rang out over each pew.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice, it proclaimed.

At the pulpit, Carroll Brown looked out over the audience. She was regal: You could trace the through line from the base of her spine to her steady neck and head, to her outstretched arms before her. A silver pendant glinted from her neck.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

Brown urged meditation and silent reflection during the first moments of the service. Lucy Gellman Photo.

That message, echoed time and time again, came during the West Haven Black Coalition’s 32nd annual tribute to King and his legacy of nonviolence and resistance. Held at West Haven’s First Congregational Church on the Green, the three-hour event brought in over 300 attendees. As in years past, it was primarily organized by Brown, who serves as president of the coalition.

“In 2018, I think we’re doing it the way Dr. King would have wanted,” she said at the beginning of the service. “It’s like a flower garden. Blacks, whites, Latinos, Asians, Filipinos all worshipping together. That was my vision for today.”

The ceremony started in 1986, the same year King’s birthday was declared a national holiday. Brown has been the primary force behind it for 32 years, stepping down only during illness last year. In an attempt to pass the baton this year, she appointed Elder Andre Rodgers to emcee the event. Amidst a packed lineup of political officials and Christian leaders from New Haven and West Haven, both he and Brown circled back to a similar point—King’s message, always urgent, may be more important now than ever.

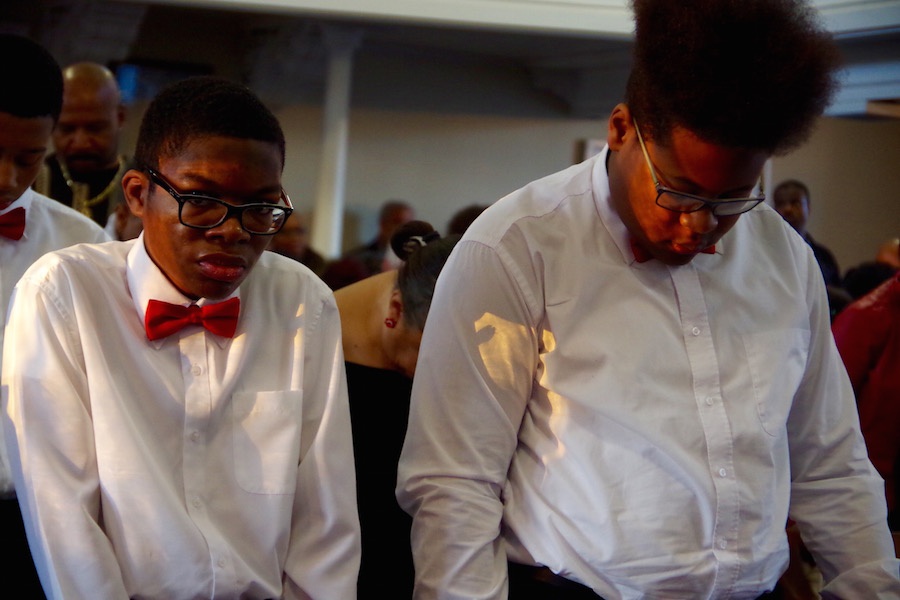

Members of the Unity Boys Choir, directed by Lillie Perkins at the event. Lucy Gellman Photo.

“Dr. King was a fierce opponent of nationalism,” said Rev. Carl Howard, associate pastor at First Congregational Church in West Haven, as he set the stage for a long lineup of speakers who included U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal, Lt. Governor Nancy Wyman, West Haven Mayor Nancy Rossi and New Haven Mayor Toni Harp. “How dare we be so silent with the hypocrisy of those who do things in the very name of Christ that we serve?”

One after another, both speakers and vocalists took the pulpit to deliver the same message, and urge strength and resilience under the administration of Donald J. Trump. Rossi, who has been a member of the West Haven Black Coalition for around 15 years and serves as West Haven’s first-ever female mayor, urged attendees to pause and reflect on King’s words considering what they could do in their own lives to drive “the arc of progress to bend toward a brighter day.”

Both U.S. Sens. Richard Blumenthal and Chris Murphy, the latter of whom delivered his words through a letter to the group, tied King’s legacy to the fight for affordable and accessible healthcare, public education, and reduced gun violence, the very thing that brought King’s life to an end. Lt. Governor Nancy Wyman said she was certain that “if we could bring him back, the world would be a better place.”

Dr. Patricia Brett brought the audience back in time to the day of King’s assassination, when she was a grade schooler growing up in Washington, D.C. On her way back to her home from downtown Washington, she recalled watching from a city bus as riots, garbage fires, and looting broke out neighborhood by neighborhood, an urban quilt unraveling before her eyes. When she ran the final stretch to her home, her mother all but pulled her into the house, shutting the door behind her with the words “Dr. King has been killed.”

“My chocolate city was burning to the ground,” she recalled.

New Haven Mayor Toni Harp took a more direct approach to King’s implications in 2018.

“[A year ago] we knew that there were little evidences of what we might call racism, but we couldn’t really put a finger on it,” she said. “Well today, we can put a finger on it. What it says to me is that you can’t ever take anything for granted … that freedom isn’t free. What Dr. Martin Luther King taught us is that you can resist with dignity, and peacefully, but you must resist. And you must call it what it is.”

Ryan Klauder, a seventh grader at DOMUS academy, looks on as a plate for a freewill offering is passed around. Lucy Gellman Photo.

But no one, perhaps, felt or spread that message as fervently as Rev. Vivian Coleman, pastor at the House of Jacob in West Haven and first woman to preside over the invited speaker portion of the program. Delivering a 20-minute sermon premised on “Lord, don’t move my mountain, but give me the strength to climb,” Coleman descended first from the pulpit down into the church, the microphone cord snaking behind her as she danced down a red carpet in blocky black heels.

“Dr. King, he knew that God was his strength! He knew that God was his protector! That God was his security!” she cried, applause and whoops of preach! and Yes yes drowning out the end of her sentence. Channeling Psalm 27—The Lord is my light and my salvation; Whom shall I fear—she continued.

“I tell you: young people, men and women, you don’t have to fear nobody. You don’t have to be afraid of nobody. When you know that God has your front, God has your back, God has your siiide.”

Coleman: "People are gon’ talk about you. People are gon’ to stab you in the back. That’s gonna happen." Lucy Gellman Photo.

Around her, the church was already rising to its feet. Coleman pivoted from one side of the church to the other, locking her eyes with congregants as she froze and unfroze, a sort of divine pop-and-lock of a dance. She pressed on to the next verse: When the wicked, my enemies and my foes, came upon me to eat up my flesh, they stumbled and they failed.

“People are gon’ talk about you. People are gon’ to stab you in the back. That’s gonna happen,” she half-sang. “They hate how you look for no reason at all. Hate the color of your skin.”

“But what did Dr. King say about that?” she pressed on. “He said: I have a dream. That one day, my four little children will live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of your character.”

She stepped to and fro at the front of the church, marching in place as a pulsing, propulsive drumbeat started from a band at the front of the church. “Here on today, we should be able to see it as a blessing that Black, White, Hispanic, everyone is in fellowship together,” she proclaimed. “Dr. King says, let freedom ring … well what about here in West Haven? He says, let’s speed up that day when all of God’s children … Black. White. Jews! Gentiles! Protestants! Catholics! We all, we all pray together.”

Toward the back, a white woman ran up to the front and locked hands with Coleman. The two lifted their arms toward the ceiling, forming a sort of mountain with their limbs. The audience cheered as they did a little two-step at the front of the church, Coleman’s husband running through a scale on the piano.

“And we all sing the old Negro spiritual: Free at last! Free at last! Thank God almighty, I’m free at last!”