Immigration | Institute Library | Politics | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts

| The poster by artist and activist Margaret Roleke. Photos contributed by Stephen Kobasa. |

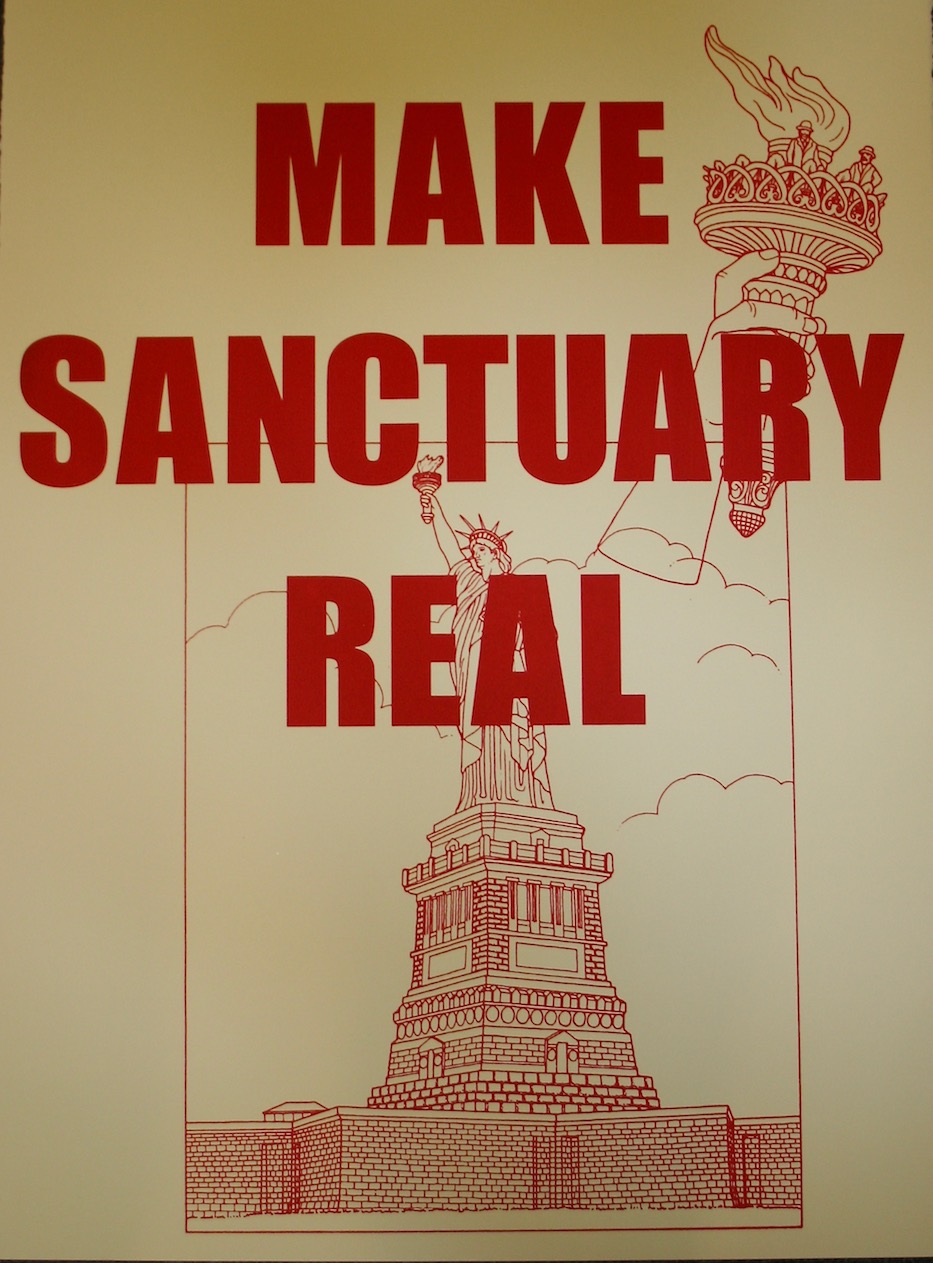

“MAKE SANCTUARY REAL” states a poster in bold, red letters. Behind the text, a depiction of the Statue of Liberty floats on the cream paper. From the narrow border of this drawing, another enlarged copy of Lady Liberty’s hand clutches her torch. Next to her flames, two small men appear in an area of the physical monument—accessible only by a long and narrow ladder—that has been closed to the public for over 100 years.

This petite poster, created by Easton-based artist and activist Margaret Roleke, establishes the political tone of Finding Home: A Campaign for Sanctuary. The show runs at the Gallery Upstairs at the Institute Library now through March 14.

In Finding Home, curator and retired educator, journalist, and longtime immigrant rights activist Stephen Kobasa probes shifting attitudes toward immigration, while anchoring the issue to a specific community. Artists Paul Bloom, Joy Bush, Eric Epstein, Jason Noushin, and Roleke all responded to an open call by Kobasa to design posters related to the theme.

Two sculptures by Noushin and a series of photographs called “Portraits of Dignity” by Marc Hors also contribute to the conversation.

| Installation view. Jacquelyn Gleisner Photo. |

The campaign to make New Haven a sanctuary city is not new. In 2007, then-Mayor John DeStefano created the Elm City Resident Card in an attempt to protect immigrants of all backgrounds, including those who were undocumented. For several years, the immigrant rights group Unidad Latina en Acción (ULA) has been pushing for official sanctuary city status in the city’s charter.

Last year, former Mayor Toni Harp announced an executive order on sanctuary to protect undocumented immigrants in the city. In both his campaign and first five weeks in office, Mayor Justin Elicker has vowed to work with the Board of Alders on stronger sanctuary city legislation in the city.

New Haven is also home to multiple sanctuary congregations, in which immigrants have taken refuge from Immigrations and Customs Enforcement Officials for months and sometimes years.

Artists have also answered the call. The exhibition Sanctuary Cities and the Politics of the American Dream at Creative Arts Workshop last fall investigated the same premise, with one fundamental difference. Curator Luciana McClure’s approach was notably more inclusive in the volume of artists represented, as well as the attention to women, people of color, and artists who are immigrants themselves.

By contrast, this small group show has a narrower focus: the posters have the potential to be utilized during protests and rallies for the cause.

Among the selected agitprop posters, text is a central factor. Adopting similar palettes with variations of red and black—hues that seem to communicate the gravitas of the subject—the posters share many similarities.

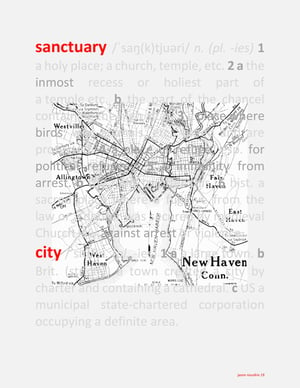

Every piece mentions the word “sanctuary” and most include the name of this city, accompanied by simple imagery. Noushin conflates a map of the city with the definition of the word. Bloom’s submission contains a photo of the Women’s March in New York City, connecting the fervor of the 2017 feminist protest with the agenda for this exhibition.

Most succinctly, Bush’s poster encapsulates the motivation of the show with the statement, “A Sanctuary in Law, Not Just in Word.” It’s a reminder that New Haven has yet to adopt the legal designation of a sanctuary city although it ostensibly operates as one. In his first months as mayor, Elicker has verbally committed to the issue, and a draft statute is being prepared for the New Haven Board of Alders to consider.

Rallying behind the efforts of Unidad Latina en Acción (ULA), Kobasa said he believes that this campaign carries significance beyond legislation. The official designation signals to immigrants—as well as community members—the values of this city.

The notion of sanctuary is vast, as are the struggles of those escaping harm around the world. Displayed on top of three large cases positioned around the room, a series of black and white portraits by Hors explores a temporary iteration of the show’s crux. Hors’s images document Syrian and Afghan refugees inside the Ellinikon Refugee Camp in Greece from 2016.

| Marc Hors Photo. |

Throughout this body of work, the subjects engage the viewer directly in these staged works. No candid moments are captured; rather Hors highlights the relationships between people by presenting sisters in locked arms and families huddled together.

While Hors’s photos trace the first steps toward a more permanent type of refuge, a couple of sculptures by Noushin—a Hamden-based artist of Iranian heritage—brings the theme of the exhibition into the present. Fesenjoon (2017)—the title refers to a type of stew Noushin’s mother prepared throughout his childhood—takes the form of a crouching, headless figure. Swaddled in raw canvas, the figure’s arms cradle the skull of a deer.

Persian calligraphy covers the surface of the skull as well as the figure’s exposed back. Colorful imagery of people carrying crosses, armor, and weapons seem to have been culled from a storybook based in the Middle Ages, but the narrative remains indecipherable to a contemporary viewer. Unlike other works in the show, Noushin trades an overt statement for more poetic and personal allusions to distant times and cultures.

“Resistance and advocacy take many forms,” said Kobasa, who points to artists to provide clarity in uncertain times. At their worst, the posters in Finding Home are too clear, the artists failing to elevate their passion for the agenda into lasting gestures. Graphic Design, by nature, can be ephemeral and disposable. More importantly, Kobasa’s solicited these works to create an opportunity for artists to respond to this issue and perhaps, agitate progress in our own backyard.

Beyond New Haven, sanctuary cities remain a contested issue. During the 2020 State of the Union address, President Trump excoriated New York City and the state of California, linking their city and state sanctuary designations with incidences of extreme violence. As artists question the impact of their efforts against this backdrop of political divisiveness, Kobasa offers a potential answer. “Public images as part of a campaign are a useful way to think about how art can function in our time,” he explains. While New Haven awaits a final vote, artists take action.

Finding Home: A Campaign for Sanctuary runs through March 14 at The Gallery Upstairs at the Institute Library, 847 Chapel St. in New Haven. To find out more about the gallery’s hours and collection, visit its website.