Creative Arts Workshop | Immigration | Politics | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts

| Maria de los Ángeles’ work draws on her own experience as a DACA recipient and fine artist. Lucy Gellman Photos (all work by the artists) with permission of Creative Arts Workshop. |

The dress is almost too much to take in at first. From the neckline, it blooms into color: blue and red squares of an American flag on each sleeve, and a heart-shaped red, white and blue collage just beneath the breasts. A neat line of red-orange stitches winds down the sternum, attached to a pendant. At the waistline, it slides into a welcome riot of color: yellows and reds mingle with words and images, painted thickly enough that they gleam in the light.

Maria de los Ángeles’ “I love America” is one of over 100 staggering, heart-rending and thought-provoking pieces in Sanctuary Cities and the Politics of the American Dream, running at Creative Arts Workshop (CAW) now through Nov. 9. A collaboration between CAW Director Anne Coates and curator Luciana McClure—who is herself a Brazilian immigrant doing sanctuary city work—the show explores and expands the meaning of sanctuary, extending it to indigenous rights and land reclamation, more humane policing, and the end of an industrial carceral state. It is funded by a grant from the International Association of Greater New Haven.

| CAW Director Anne Coates: “I feel very pleased and very proud to have been able to present this platform for conversation, which for me is essentially about human rights." |

A month-long series of onsite events including collaborations with Interference Archive and Sanctuary Kitchen will accompany the exhibition. The show comes as New Haveners continue their call for official Sanctuary City status, which has yet to come before the city’s Board of Alders despite an executive order issued by Mayor Toni Harp earlier this summer.

“I feel very pleased and very proud to have been able to present this platform for conversation, which for me is essentially about human rights,” Coates said at an opening reception Thursday night. “I care deeply about making this space available to as many people as possible, to engage with creativity on all sorts of levels. And so for me, to open my arms wide, to open our arms wide, is very meaningful to our vision.”

| Amira Brown's Looking Homeward. |

Inside the space’s two-floor gallery—and through new collaborations with the Connecticut Bail Fund, Unidad Latina en Acción, Planned Parenthood of Southern New England and others—that mission comes alive in vibrant color. Multimedia work packs the walls, hangs from the ceiling and sits installed on the floor, somehow economical even in a total, very welcome takeover of the space.

It beckons from the street, visible through the building’s huge front-facing windows. Many of the pieces call to the viewer right away, drawing them closer with intricate detail.

On the first floor, one of those is Kat Chavez’ 2018 “Only The Earth Knows,” an installation of silkscreen and acrylic-on-canvas squares that have been cut roughly, with their threads still exposed. Piled before the viewer and pinned to a temporary wall, they sing with resonances: woodblock prints and early cyanotypes, nature before anything has been picked or mowed, blood at its most immediate, when the body blooms and smells like copper.

| Detail, Kat Chavez’ Only The Earth Knows. |

Not one of them is exactly the same, which gives the viewer pause. Some are clean and tidy, statements in perfection. Others smudge and blur, red covering red as if the plants are half-submerged, or have slipped under this surface entirely.

They are intensely tactile, and the urge to touch them, hold them in one’s palms, and pick them up becomes almost too much to bear the longer one looks. It feels like part of the point, as if the viewer is also implicated in the piece.

“I am evoking history in everything I do, whether that be personal history, cultural history, or art history,” Chavez writes in an artist statement. “My body belongs to a lineage of womxn and femmes who have questioned the abuse of our individual and collective bodies, seeking new forms of healing and empowerment through the arts.”

| Detail, White Space. White Noise. Family Separation at the Border. |

Another is Susan Clinard’s “White Space. White Noise. Family Separation at the Border,” an all-white sculpture depicting huddled masses that are bent and broken just so. Across a frieze that looks almost holy, figures reach for each other, looking out at the viewer as if to ask for help. Their bodies are not so different from the bodies that stare back: mothers and children, just trying to live.

Because the piece is installed below eye level, viewers must lean down to see it, experiencing their own discomfort or unease as they do. A closer look reveals a more juxtaposition: the sheer beauty and iconography of the piece rubs right up against the violence and inhumanity of its subject matter. Family separation, Clinard seems to say, isn’t just wrong: it’s a crisis of profound and entirely manmade moral proportions. What are viewers going to do about it?

Clinard’s question is one that rises again and again, taken on by a number of artists. In a back room that is easy to miss, poetry by local author laura Altshul joins writing from several New Haven high school students, poems arranged in a row that viewers can pick up and read. Simone Alter Muri’s “Plight of the Refugees (Mexico and the Internment Camps)” layers history on top of history, making her viewers how many times they will let the past repeat itself.

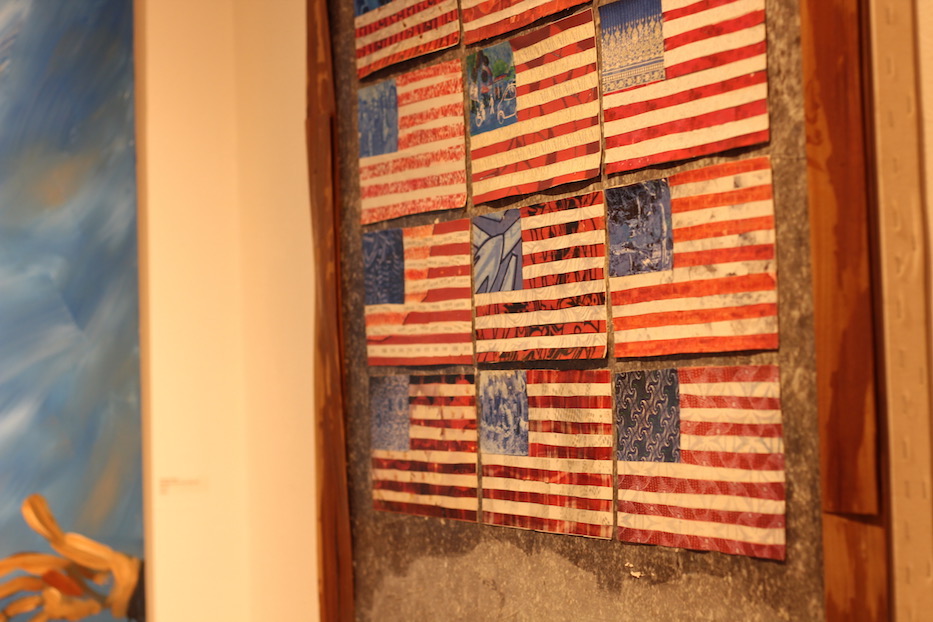

| Sarah Bolitzer, All America. |

Indeed some of the most intriguing works in the show probe the complexity of migration, sanctuary, and statehood—including what one gains and what one loses in the process. In the main gallery, Kim Weston’s “Aztec Warrior”—a long exposure that is worth at least an hour of close looking on its own—raises questions on indigeneity, displacement, and collective visual memory.

Upstairs, artists Zohra Rawling and Camille Eskell both draw on family histories of migration and cultural assimilation, past meeting present through the literal binding of materials. In Rawlings's "Untitled," she has sculpted a tower that seems to melt despite its stillness, flickering to reveal a pendant of an Assyrian lamassu inside. At the opening Thursday, she spoke about the difficulty of leaving that piece of her in the sculpture—she has had the necklace with her for decades—but "it had to happen" for the piece to feel like a complete statement on what one loses in gaining a new home.

In Eskell's "Marriage Turban Fez: To Have and to Hold," traditional male and female headpieces from the Middle East come together, in a stunning installation that warrants many long, close looks.

"Marriage Turban Fez: To Have and to Hold features a traditional Mid-East Turban (male headgear) adorned with a bridal veil bordered by family portraits," she writes in a statement on the piece, one in her series "The Fez as Storyteller." "The piece speaks to enforcing a stronghold on the family group, especially the females.

| Detail, Camille Eskell's Marriage Turban Fez: To Have and to Hold. |

Back on the first floor, artist Jesus Torres brings the viewer literally to their knees with “La Virgen de Escultura,” asking them to join him in an act that makes a secular, charged space suddenly holy. WonJung Choi's “Borderless” presents a pair of nonfunctional slippers, metal pieces that have been brought together to form a cohesive object meant (at least in theory) for movement. Jaishri Abichandani takes it in a different direction, pointing to the need for intersectionality in political movements.

Some of the works bring the border crisis directly to New Haven, reminding viewers how deportation as much a local epidemic as a national one. And they are right to do so: this month, immigrant Nelson Pinos has spent almost two years apart from his home, seeking sanctuary in a church downtown.

| Marsha Borden, A Migrant Child's Blanket. |

On the second floor, textile artist Marsha Borden stuns with her disarmingly simple “A Migrant Child’s Blanket,” in which she has sewn a child-sized quilt into the type of aluminum blanket used in hieleras or “ice boxes,” short-term detention facilities that have been so named for their frigid, often life-threateningly cold temperatures and often hold migrants for much longer than a few days.

The image, which takes a moment to register, stops one in their tracks: it is visceral and deeply empathetic all at once. And it’s thought provoking: while hieleras have become part of mainstream coverage during Donald Trump’s presidency, they are a trademark of the Obama administration. Without the Deporter-In-Chief, it asks, would we be where we are now?

Others suggest that there might be momentum in the movement for sanctuary—and that there must be, to get to a place of basic humanity in this country. In two prints, photographer Ellen Jacob shows the very cruel and real time consequences of an unjust immigration system, depicting children with parents who are undocumented immigrants, and thus afraid to show their faces.

| Nadine Nelson, founder of Global Local Gourmet, with attendees at the opening. Her piece Rice and Beans; Neighbors Unforeseen asks a series of prompting questions to spark dialogue. |

Multimedia artist and chef Nadine Nelson has used her work "Rice And Beans; Neighbors Unforeseen" as a prompt for cross-cultural connection, placing dry rice and beans in the center of a table where viewers are meant to sit and talk.

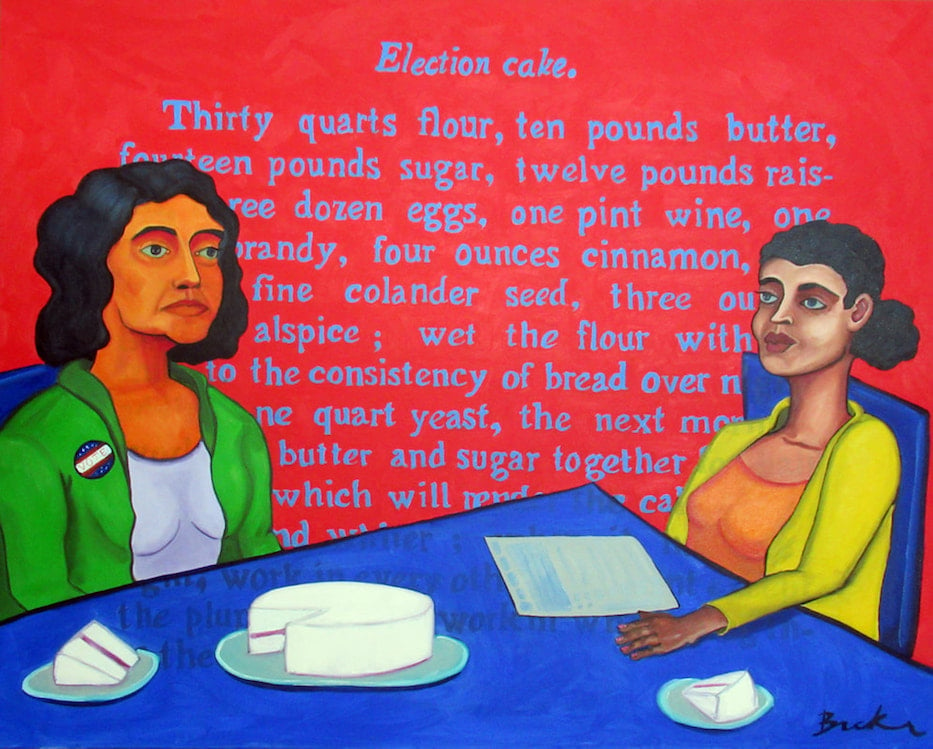

In painter Nicole Bricker’s “Election Cake,” two women sit at a dinner table, watching each other over a white cake layered with purply-red jam. One wears a sticker that reads "Vote." The other sits back, a blue-and-white form before her. Is she a first-time voter? Maybe a new citizen? Behind them, a recipe runs from side to side like ticker tape, listing ingredients for a cake that seems unfathomably large, with literal pounds of ingredients.

The painting is hopeful, in ways that the viewer may not even realize at first. Election cakes are a real thing: they have their sticky-sweet origins in the American Revolution, when groups of women would bake dense, self-rising spice cakes for soldiers. Studded with dried fruit, they were originally called muster cakes—which became election cakes after the revolution, when voting became more important than fighting.

| Nicole Bricker, Election Cake. |

There’s a bitter irony there, of course: the cakes’ bakers couldn’t vote, and neither could people of color. Meanwhile, they did most of the physical and emotional labor that supported the war, and then the sputterings of early and fragile American Democracy. So what does it mean to have two women, perhaps Latinx, women sitting around the same concoction, one getting ready to vote for the first time?

In this sense, McClure has succeeded wildly. She is a curator with a sharp eye, and has placed pieces beside each other in such a way that they talk back not only to viewers, but to each other. Now that the show is mounted—an effort that she said took a small village—she is using it as a lens to explore art as activism in her work and in the city.

| Detail, Lawrence Ciarallo, OUR DREAMS (chasing invisible butterflies with a net). |

“I think we need to really be intentional about the work that we want to do,” she said Thursday, praising CAW for opening the show to the community. “It’s what we have to do. If we’re not being intentional about the change, we can’t expect it to happen.”

“We’re in such a time where we’re not coming together,” she added. “So to be able to share space, commune with one another, laugh, hug—just be in a space and have positive feelings, it feels like a gift. It feels like something we should hold onto.”

Creative Arts Workshop is located at 80 Audubon St. Gallery hours are 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. Monday through Friday and 9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. on Saturday.