Culture & Community | Immigration | Refugees | Sanctuary Kitchen | Arts & Culture | Culinary Arts | Arts & Anti-racism | Ramadan

Chef Rawaa Ghazi. Lucy Gellman Photos.

For chef Rawaa Ghazi, every recipe tells a story of home. In the saffron-scented Mutabbaq Samak, she can remember her mother in the kitchen, keeping watch over bubbling pots of rice as she spiced fish and sliced cashews and almonds. In the Shorbat Adas, there’s the taste of breaking fast at the end of a long day with her own children. When she makes Timman bil jizar, she can nearly smell Ramadan observances of years past, when extended family in Iraq would still-hot bring dishes into each other’s homes.

Ghazi, who came to the U.S. from Iraq in 2010, is a chef at Sanctuary Kitchen, a refugee- and woman-powered culinary outfit that works out of CitySeed’s 109 Legion Ave. kitchen. This week, she and fellow Sanctuary Kitchen chefs are preparing their final Ramadan menu of the month, as they enter the festival of Eid on Thursday evening. For many of them, it marks a year of new and evolving Ramadan traditions far away from their first homes.

“For me, you appreciate the food, and also you think of others who have less than you,” Ghazi said as she adjusted a powder-blue headscarf. “When you have everything, there is no humility in that. During Ramadan, when we say dua [prayer], we say, ‘Please God, keep this gift always for us, and give it to other people who don’t have it.’”

Sudanese Ka'ak, before baking. The cookies will be coated with powdered sugar when they come out of the oven.

This year, part of that observance is sharing their own flavors and memories of Ramadan with the wider New Haven community. Observed each year in the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, Ramadan marks the revelation of Qu'ran to the Prophet Muhammad. The month, which this year runs from March 22 to April 20, is marked by both fasting and daily prayer. This Thursday night through Sunday, Muslims will celebrate Eid al-Fitr, which marks the end of the holy month.

Since the observance began last month, Sanctuary Kitchen has piloted weekly Ramadan menus based on a subscription model that they first rolled out in 2021. One week, honoring Sudanese Chef Azhar Ahmed, included beef stew with okra, orzo soup, and arugula salad with a lemony dressing. Another, dedicated to Afghan Chef Homa Assadi, featured beef kofta, battered and fried potatoes, vegetable-studded soup, and fragrant butternut squash. A third, with Parvine Toorawa’s Mauritian flavors, boasted pastry turnovers, a savory oat-and-chicken stew, delicate pea and potato turnovers, and cardamon-kissed Gulab Jamun.

Naseema Gilson, program director at Sanctuary Kitchen, said that the menus came as an opportunity to honor the different cultures that build, sustain, and create support within the organization. Since 2017, Sanctuary Kitchen has welcomed chefs from Afghanistan, Mauritius, Syria, Sudan, Nepal and Iraq. It is also a sisterhood; all of Sanctuary Kitchen’s chefs, employees, and volunteers are women.

Sudanese Chef Azhar Ahmed, who did not wish to be photographed, making falafel. Lucy Gellman Photos.

On Tuesday afternoon, the Legion Avenue kitchen bustled, conversation at a low hum as Arabic, Farsi, and English wove through the space. At one end of a long counter, chef Parvine Toorawa sliced neat triangles of pita bread, depositing them into plastic bags and tying the tops neatly. At the other, Ahmed lifted emerald, droplet-covered handfuls of parsley from a bowl and began to finely chop them for falafel. Behind her, huge steel pots of saffron rice and peppery chickpeas rolled to a boil.

This year, Ahmed said, Ramadan has felt difficult and heavy. Since mid-April, she has watched from afar as fighting between the Sudanese army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) escalates in Sudan’s capital city of Khartoum, where most of her family members still live. When she speaks to family members, they are hiding in their home, out of sight. Sometimes, she said, they talk from beneath the bed. Sunday, they saw a neighbor killed for simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

This week, her relatives struggled twice to find a hospital that was still in operation: once when her brother needed surgery, and once when her cousin’s wife went into labor, and required a cesarean section. It felt like a miracle when they delivered a healthy baby, she said, pulling up an image of a fat-cheeked, scowling infant on her phone. As of Tuesday, 39 of the country’s 59 hospitals had been shut down by the violence, according to the Sudanese American Physicians Association.

The news is especially devastating during Ramadan, which is supposed to be a reflective time for the nation’s Muslims, and Muslims living across the globe. At home, she doesn’t know how to explain the fighting to her two children, Lames and Kutti, who are 15 and 5 years old. At work and in her daily interactions, she said, it feels like “no one is paying attention to the situation that is happening.” When she breaks her daily fast in the evening, her thoughts turn toward fellow Muslims who have been without food, water, and power for days.

“Some people, they die because they don’t have water,” she said. “They are killing so many people in one time.”

Chef Homa Assadi, who did not want to be photographed, making the first part of the shor nakhod. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Every so often, Assadi stirred the chickpeas behind her, releasing threads of white, spiced steam into the air. She explained that they would become shor nakhod, an Afghan dish that pairs soft, creamy cooked chickpeas with boiled potatoes and green chutney with mint and cilantro. For her, the holy month is a time to look inward and reflect on those in need across the globe. This year, that includes friends, family and neighbors who are still in Afghanistan, where she grew up.

“Ramadan is very special for all Muslims,” she said, adding that she is extremely excited for Eid celebrations that will unfold between Thursday night and Sunday. She turned around, saying something quietly to Ahmed as she lifted a large container of turmeric.

At the other end of the counter, Toorawa reflected on her own Ramadan experiences as she checked off a list that included hummus, pita, and peanut sauce. Born and raised in Mauritius, she grew up celebrating Ramadan with her cousins, of whom she said there are over 100. At home, she learned to recognize “the smells of Ramadan,” from her mother’s beef samosas to Haleem. The latter is a thick soup made from scratch with oats, grains, chicken and sometimes lamb and often spiced with ginger, turmeric, coriander and cumin.

“My mother hated cooking!” she said with a laugh. “Hated it!” By the time Toorawa was 14, she had started to take over operations in the kitchen, thanks in part to.a nanny who helped her learn. Decades later, she said, she loves the culinary ballet that Ramadan brings. Mauritian food is a fusion of cultures: there are Indian, Creole, French and East African influences, which means that her food folds in a layered history as she cooks.

“It’s great,” she said of the Ramadan menus, including one that she designed earlier this month. “I love to share my culture.”

Chef Parvine Toorawa. Lucy Gellman Photos.

After moving to the U.S. 25 years ago, Toorawa has lived two and a half decades of Ramadans across multiple U.S. states, including Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Upstate New York and Connecticut. During that time, she became a mother twice over; she now talks to her daughters about their own observances of the holy month. One, who lives in Oxford, has found herself braving a 16-hour fast each day, because of how late the sun sets in England.

For her, “Ramadan is discipline,” she said. Each day, Toorawa rises around 3:45 in the morning, to have time to eat the pre-dawn Suhur meal and say the Fajr prayers before sunrise in her North Haven home. Normally, she said, she and her husband eat Haleem, toast and tea before praying, then begin a fast that will last until at least 7:30 that evening. If she can, she goes back to sleep for a few hours, then rises again to head into Sanctuary Kitchen.

In addition to food, from which she abstains between sunrise and sunset, “I deprive myself of things I like to do,” she said. For her, that includes listening to music and watching television. At work, she still tastes her cooking to make sure that it is adequately spiced and salted, but cannot swallow it. “We have to spit it out,” she said. By Tuesday, she was ready for the 72-hour-countdown to Eid. Each year, she and her husband celebrate with a party at their home.

“I’m hanging in there!” she said with a laugh. “The last few days are always the hardest.”

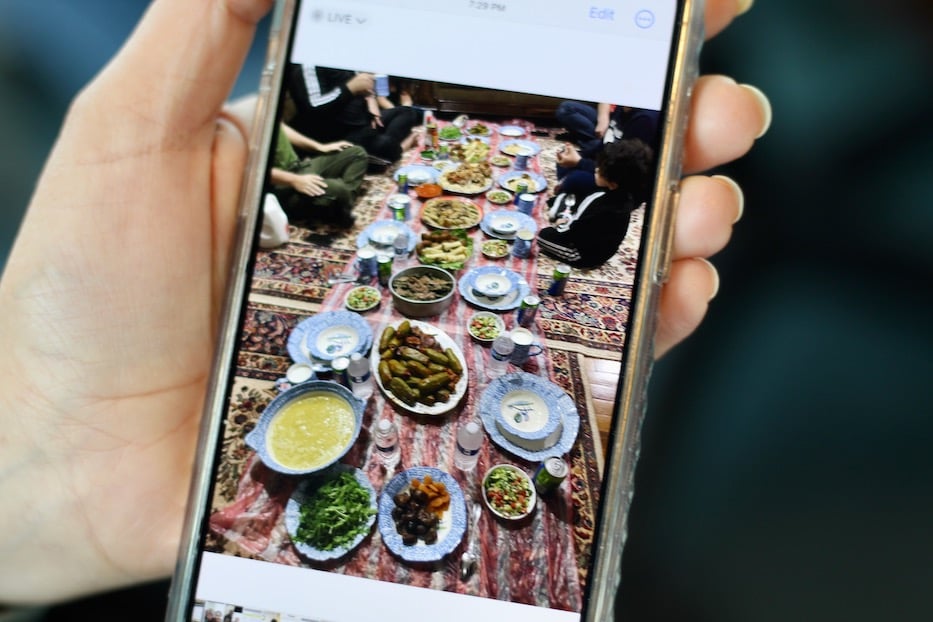

A nightly Iftar at Aminah Alsaleh's home. Lucy Gellman Photos.

At her computer, Assistant Kitchen Manager Aminah Alsaleh said she too was excited for Eid—and still braving the difficulties of observing Ramadan in the U.S.. Born and raised in Homs, Syria and displaced to Jordan by the Syrian Civil War, Alsaleh and her family arrived in the U.S. in 2016, on the night of an election fueled by xenophobia and anti-immigrant rhetoric.

In New Haven, she and her husband, Issa Aldabaan, built a life for themselves and their children from scratch. When she first joined Sanctuary Kitchen as a chef, Alsaleh also built out a catering company dedicated to food that she had grown up eating, and learned to cook from members of her own family. In the years since, she has learned to drive, watched her children acclimate to schools in New Haven, and in March of last year secured U.S. citizenship.

Still, “Ramadan here is hard,” she said. In Syria, where 90 percent of the population is Muslim, work and school operate on a different schedule during Ramadan. “We all sit down together and everyone will share food.”

In New Haven, nothing stops for Ramadan, she said. Her children still have school, and have complained that it’s too hard to fast when they are trying to concentrate on lessons, and peers are eating around them. Aldabaan currently works a late evening shift three days a week, meaning that he is not always home for Iftar with the family. When he gets home around midnight, he helps Alsaleh prepare food before taking his own Suhor, praying Fajr and then going to bed. Before dawn, he and Alsaleh eat eggs, labneh, olives, cheese and “lots and lots of water” to sustain them until dusk.

Still, she said, their nightly Iftar is a chance to think about all she is grateful for. When she gathers with her four children, it is over a spread of dates and yogurt, fresh stuffed zucchini called mahshi, hummus and grape leaves, kibbeh, lamb, lentil soup and salad. Each night after the meal, she brings out baklava, kanafa, and other sweet treats that her kids devour.

During Ramadan, Alsaleh sends money back home, so that her family and friends can afford the food and clothes that come with Eid celebrations. While it is a struggle—she and her nine-year-old daughter are currently at odds about fasting—she said she looks forward to the month each year.

“This teaches you how to be patient,” she said, looking out the space’s street-facing windows. Cars lumbered by on Legion Avenue outside. “When you’re fasting, you feel different. I feel happiness.”