East Rock | Education & Youth | Foote School | Summer camp | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts

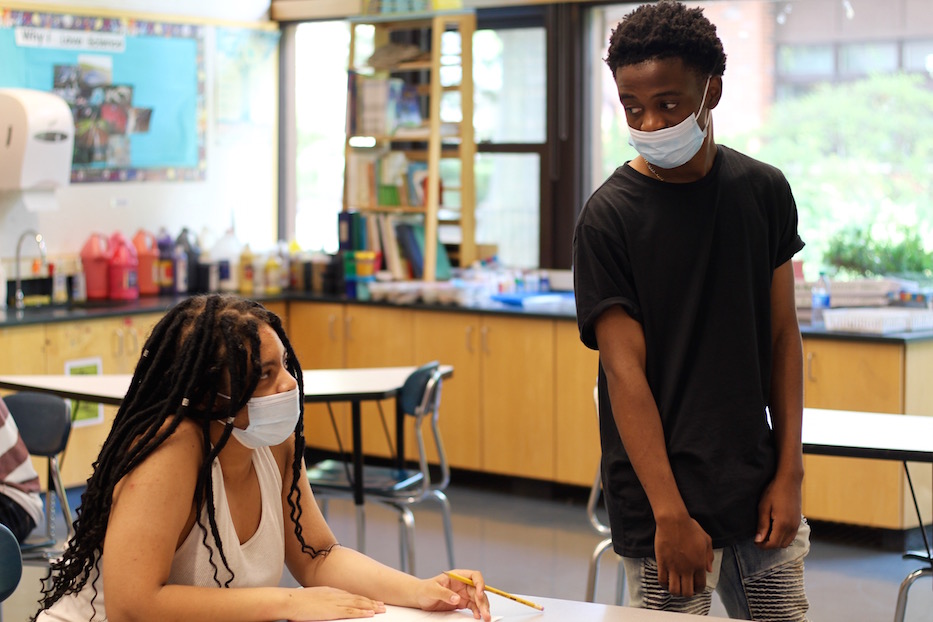

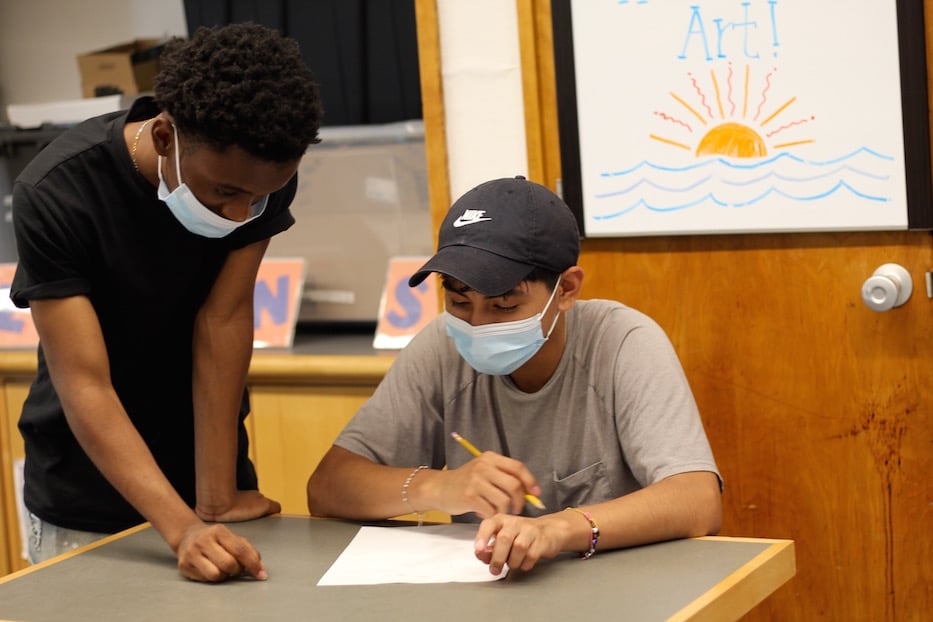

Alyssa Thomas, a rising freshman at Metropolitan Business Academy, with the artist Aime Mulungula. Mulungula graduated from Hill Regional Career High School in June and is headed to the University of Connecticut in the fall. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Alyssa Thomas sketched out a huge eye, its pupil fixed on her as soon as she drew it into being. On the top of the page, she filled in a thick eyebrow and delicate lashes. A small pride flag hovered above it in one corner; a stop sign appeared at the other. At the bottom, a red-brown teardrop fell from a long, plump duct.

The words I’m Just Human bloomed in the lower right hand corner. As she worked, artist Aime Mulungula watched intently from a few steps away, jumping in every so often to give advice.

Thomas is a student in Horizons at Foote, a summer program for New Haven Public Schools Students at the Foote School in East Rock. Mulungula is a multimedia artist, rising freshman at the University of Connecticut, and Tanzanian refugee who uses his art to challenge mainstream narratives of East African culture in American media. Last week, the two came together as part of an effort to connect students with artists in their community. The idea comes from Rachel Peet, a photographer who is also an art teacher at Horizons.

“I saw how the media falsely represented my culture,” Mulungula said. “My art flips that. Art has that power to change one person’s mind at a time. I want people to see that there’s something missing in the media.”

He pulled up a presentation titled “African Cultural Representation,” telling students about his own journey from Tanzania to New Haven six years ago when he was 11 years old. The art class, which takes place in a repurposed science classroom, fell silent save the crinkle of a few plastic water bottles. Even posters of Bill Nye and Neil deGrasse Tyson seemed to take note as they smiled relentlessly from the wall.

As a refugee resettled in a new country, Mulungula told students that had trouble squaring what he saw on television and in the news with what he experienced growing up in Tanzania. In American movies, he saw Africa depicted as if it were a single country rather than a massive continent comprising over 50 nations. The characters who appeared were depicted as poor, dirty, uneducated. There was nothing of the place that he knew and loved as home.

Drawing, which ”I’ve done as long as I can remember,” was a way to push back. Mulungula drew through middle school, starry eyed as he applied to Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School. He kept drawing when he got into Hill Regional Career High School instead. When he became an apprentice at NXTHVN his sophomore year of high school, he started learning about how to put his drawings into a narrative.

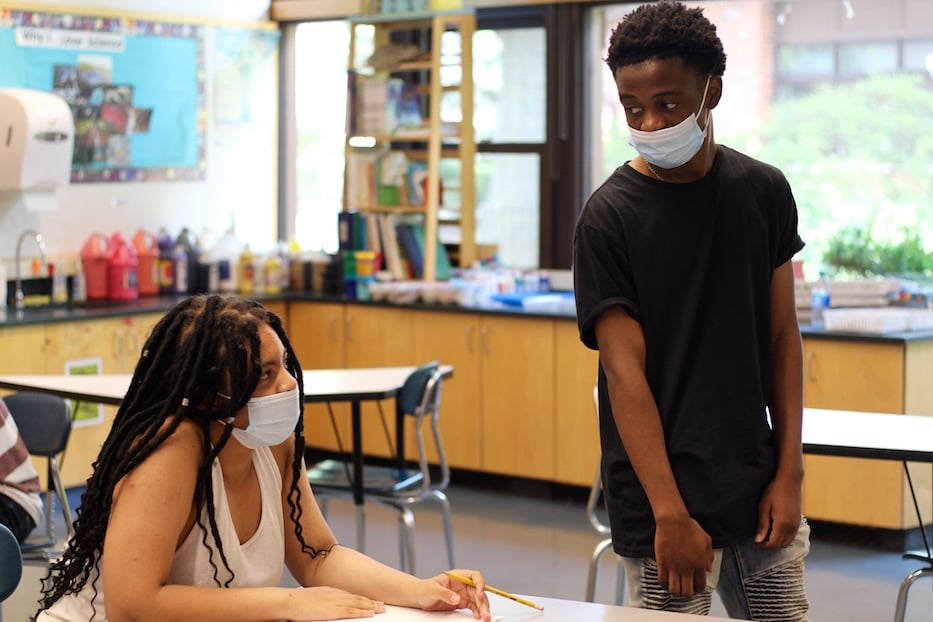

Drawings that Mulungula worked on during the pandemic. Several are currently up at NXTHVN. Aime Mulungula Photos and artwork.

Then Covid-19 hit the city. Mulungula, who was working alongside the artist Jeffrey Meris, got a sketchbook and a directive: work at home on something you care about.

“I wanted to show the diversity of Africans,” he said. He started drawing images of “what I saw growing up,” then dipped into the histories of Tanzania, Nigeria, Kenya, Benin, Ethiopia, Mali and Burundi. His original focus on East Africa grew to encompass points on the entire continent, as well as the histories of colonialism, enslavement, forced migration and extraction of natural resources. Several of the works are now on view at NXTHVN, an arts incubator in the city’s Dixwell neighborhood.

On screen, an angular rendering of a Maasai warrior appeared, red cloth flapping out to one side as a figure leaned in on a tall, pointed spear. The fabric twisted and unfurled in an invisible breeze. Across from him, three men in bright, tapered suits posed as if they were in the glossy pages of a fashion magazine. Mulungula said it was particularly important for him to show fashion, because depictions so often lean on images of poverty.

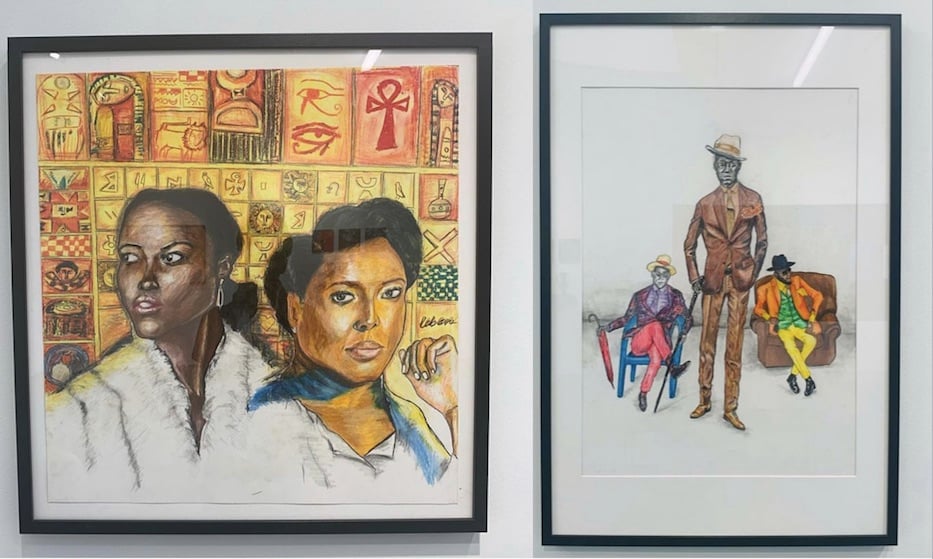

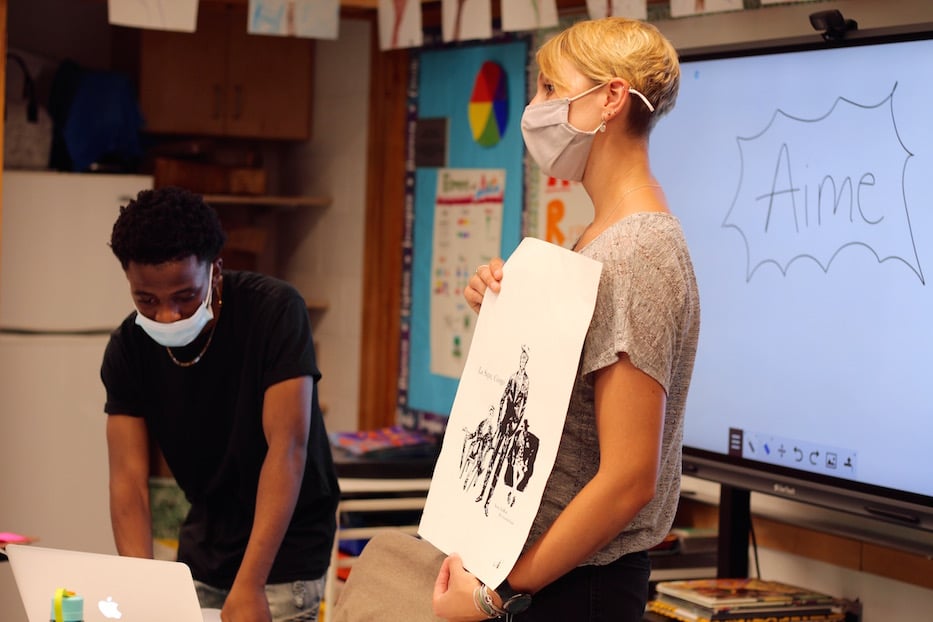

Top: Images of Haile Selassie, Mansa Musa, and Burundian writers that Mulungula worked on during the pandemic. Several are currently up at NXTHVN. Aime Mulungula Photos and artwork.. Bottom: Mulungula and teacher Rachel Peet, holding one of the artist's prints. Lucy Gellman Photo.

He changed the slide, with students wide-eyed and watching the screen. Suddenly, three drummers lifted their arms above their heads and spread their feet wide, joyous before the heartbeat of percussion filled the air. These, he explained to students, were the Royal Drummers of Burundi, draped in the vibrant red, white and green of the country’s flag. On the opposite side of the screen, he had drawn some of his favorite artists and writers from the country in blue pen. They covered the page, some locking eyes with the students as others looked off into the distance.

He switched the slide again, showing students a portrait of Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie. The contemporary urban skyline of Addis Ababa glimmered behind him. Selassie stood upright, a turquoise sash running down the front of his jacket.

“It’s not people living in huts,” Mulungula said. “It’s not people living in the forest. It [Ethiopia] was never colonized, and that’s why it is so developed.”

Mulungula and student Luis Cuapio. Cuapio will be a freshman at Achievement First Amistad High School.

While working on the project, Mulungula spent hours doing historical research. He said it became his refuge during the height of the pandemic, when the world ground to a halt and art museums and galleries closed their doors for months. It has also pushed him to think about the sheer amount of damage that colonialism has wrought on the continent. He moved on to a delicate rendering of Mansa Musa, who ruled the Mali Empire in the fourteenth century.

“I don’t really believe in God or anything, but he kind of looks like a Black Jesus,” ventured Thomas, a rising freshman at Metropolitan Business Academy.

“It makes me think of power,” chimed in Luis Cuapio, who is headed into ninth grade at Amistad Academy.

“Yes!” Mulungula said. “People forget about how rich Africa really is. The history … how powerful Africa was before slavery and colonization. It is shown often as poor, but we forget how degrading colonialism was. All this is not spoken about in the media.”

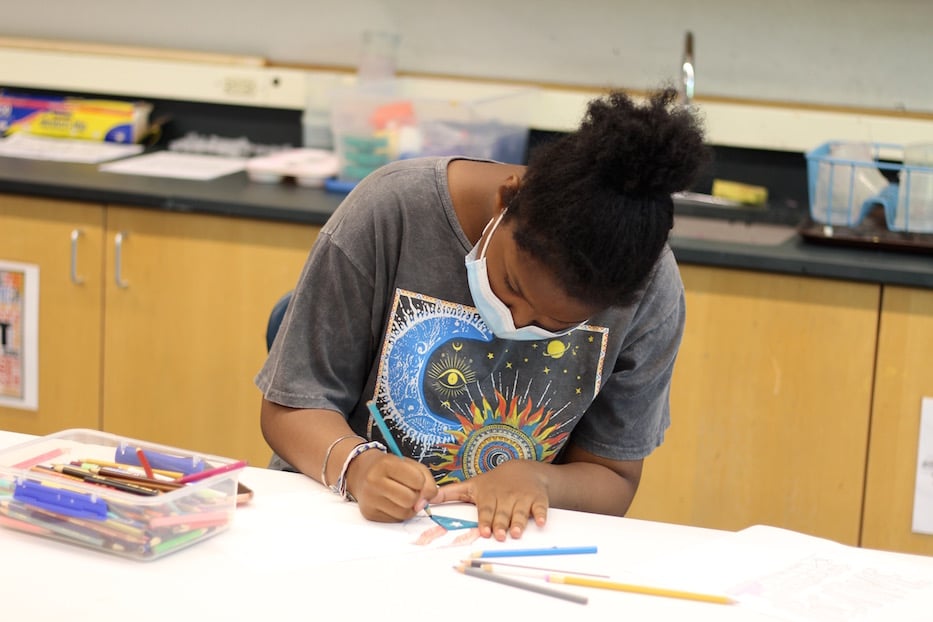

Student Elissa Matthews.

As Peet and several counselors passed out blank sheets of printed paper, Mulungula challenged students to think of “what you would like to highlight” in their own struggles for accurate representation. Neat cardboard packets and plastic tubs of colored pencils made the rounds. Mulungula walked around the classroom, stopping at desks to study students’ handiwork. Chatter rose and fell, quiet alongside the whisper of pencils on paper.

Elissa Matthews, a rising freshman at Hopkins School, carefully sketched out the first lines of a Puerto Rican flag, its stripes undulating. A hand took shape, waving it gently. Matthews said the work is an homage to her mom, who grew up in Puerto Rico and moved to New Haven when she was a young adult. With the family now in Westville, she has taught her daughter the history of that blue, red and white flag—including the gag law that made it illegal to display the Puerto Rican flag from 1948 to 1957.

“I feel a sense of pride” when she sees the flag, Matthews said.

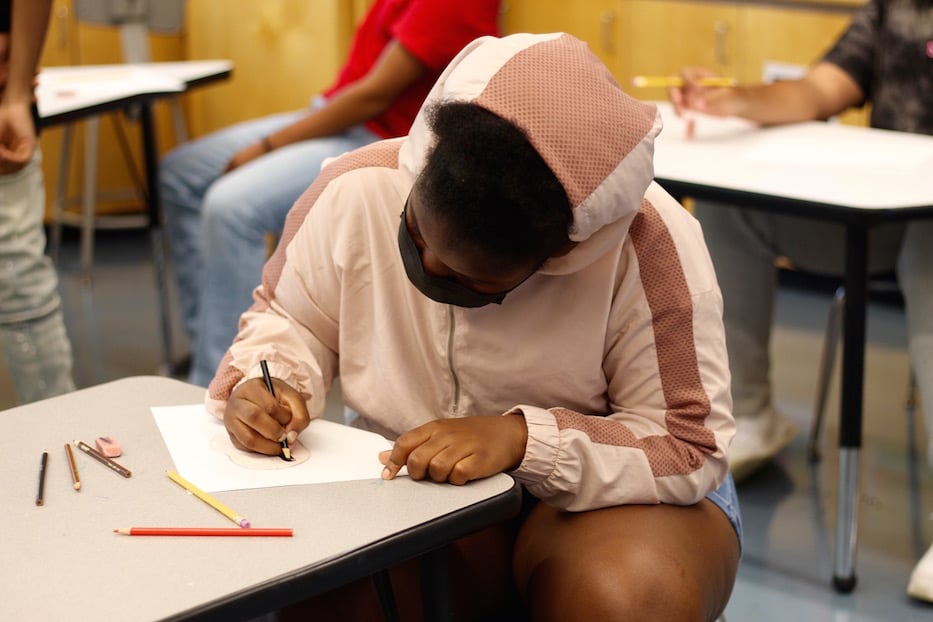

Jayana Salmone, who will be going into ninth grade at James Hillhouse High School.

At a nearby cluster of desks, Thomas drew an eye that took up nearly the entire page. She said that it represents the inner turmoil and trauma she is experiencing in her own life, particularly when thinking about gender and sexuality. At home and at school, she’s tired of hearing that her preferences “are just a phase,” she said. In the upper left, a gun with a slash through it represented an end to police brutality.

Across from her, Jayana Salmone drew a line down a long, ovular face and shaded it the color of caramel. One side was reserved for how the mainstream media perceived her: as a young Black woman who was more likely to be racially profiled and stereotyped than her white peers. On the other side, viewers got a glimpse of how she perceived herself.

Mulungula studied Thomas’ work, listening as she described each detail. For him, it was the distillation of the exercise. He praised the depth of the work, looking over its details after students had left the room, and gone on to their next activity.

“Art doesn’t have a language,” he said. “It translates to more than one person.”