Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | New Haven Schools | History | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism | Metropolitan Business Academy

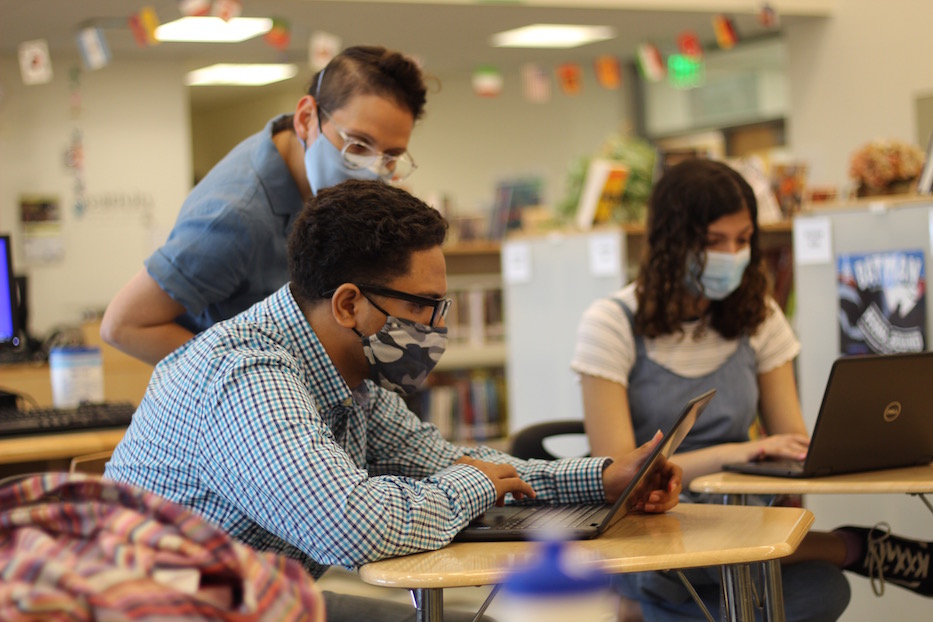

Metro High School Senior Derek Bedoya and Teacher Nataliya Braginsky. Lucy Gellman Photos.

When Derek Bedoya heard his hometown mentioned in the movie Judas and the Black Messiah, he was so surprised that he almost fell out of his chair. Four months and one research project later, he’s working to teach his peers about the Black Panthers’ footprint in New Haven—and to question what else might have been left out of their history books.

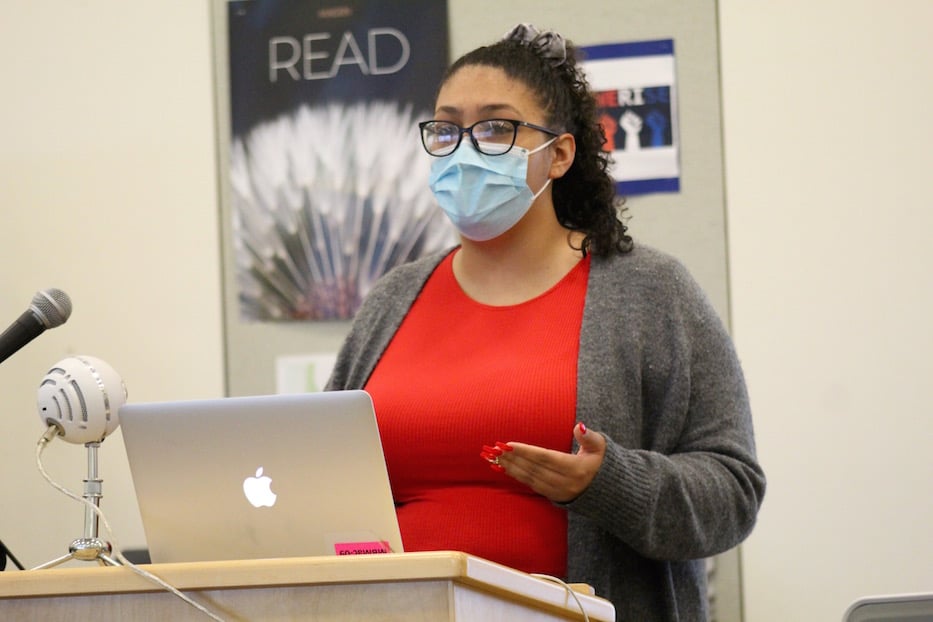

Bedoya is a senior at Metropolitan Business Academy, where students have been researching and mapping New Haven’s Black, Latinx and Indigenous history as part of Nataliya Braginsky’s African American and Latinx History Class. Friday morning, students gathered in the school’s library and on Google Meet for back-to-back presentations on their findings. Friends and community members attended in person and on Zoom, some building their own cheer section.

Although this is the class’s second year in existence, it marks the first time students are able to publicly present their work. Their new discoveries now live on an annotated map of New Haven. For the first time, students have also written works of speculative fiction; more on that below.

Michael Martinez does last-minute prep before he presents on the 1964 founding of the Helene Grant School. His story, "We Won’t Be Silenced," pushed back against a future of public services that are suddenly privatized. Braginsky (standing) and classmate Leilani Rivera are in the background.

“This class has evolved in lots of ways,” Braginsky said Friday in between class sections. “A lot had to change for so many reasons … students are at home, at their jobs, taking care of siblings. I’m trying to make sure that the curriculum that I’m teaching feels culturally relevant, but it also feels healing.”

Students’ findings come as high schools across the state prepare to offer an elective in Black and Latinx history by fall 2022. A curriculum for that course is set to become publicly available from the State Education Resource Center next month.

In the library, the air crackled with excitement and mid-morning jitters. Students slipped into a wide semicircle of desks as others signed in online with a doorbell sound. The bookshelves stood at attention, as if they were waiting with open ears. Leilani Rivera helped fellow student Michael Martinez fix the buttons on his shirt.

“Does everyone feel ready?” asked Braginsky as she checked to make sure the tech equipment was working. Two microphones—one for in-classroom amplification and one for students online—waited eagerly. A sign with multicolored fists and the words “Together We Rise” blinked out from a bulletin board against the wall.

From the moment senior Jyrese Cooper began to speak from his remote perch, it was as if the whole room leaned in to listen. For the past several months, Cooper has been researching the development of the city’s New Guinea neighborhood under Black engineer William Lanson. In 1820, Lanson began work on the neighborhood, close to what is now recognized as Wooster Square. Five years later, he was elected “the Black King” of New Haven, a sobriquet that has stuck for two centuries.

Stephanie Chapman, who researched Dr. Beatrix A. McCleary. In 1948, McCleary became the First Black Woman to Graduate from Yale School of Medicine. Chapman speculative fiction story, "Survivors and Suited," considered the possibility of increased, oppressive misogyny in the year 2321.

Cooper explained that Lanson made his mark with both housing and businesses that included “a slaughterhouse, a livery store, hotel, and a grocery store.” For a time, he was prosperous—and often found a way to share his wealth. He paid Black laborers and offered housing and work to formerly enslaved Black people. He helped found Temple Street Congregational Church, now recognized as the Dixwell Avenue Congregational Church. While the neighborhood sat beside a working-class Irish neighborhood known as Slineyville, it was not completely segregated.

But Lanson also struggled: his advocacy for voting rights and abolition made him a target. He ultimately faced harassment and violence from the state. He died in an almshouse in 1851, and much of the history temporarily died with him. A sculpture of the engineer by the artist Dana King now stands at the mouth of the Farmington Canal. Last year, activists also proposed renaming Wooster Square Park in his honor.

The class listened, the library quiet enough to hear the rustle of papers and footfalls of a late visitor. Cooper’s voice came through a speaker, clear as a bell. “I think this is important because he stimulated an economy,” he said.

The presentation opened the floor to joyous, sometimes painful findings that ranged from little-known Black graduates of the Yale School of Medicine to riots that shook the city over 50 years ago. In the space of two class sessions, long-dormant stories of Black ministers unfurled alongside the living leaders of Junta New Haven and Puerto Ricans United (PRU). A crash course in the city’s 19th century Sumner League lent new meaning to Indigenous leadership of New Haven’s 2012 Occupy movement.

Turning back the clock, Byron Hermosilla Reyes introduced his classmates to James Pennington, who emancipated himself in Maryland in 1827 and became the first Black person to take classes at the Yale Divinity School in 1834. Four years later, Pennington officiated the wedding of another formerly enslaved man—the orator and abolitionist Frederick Douglass. He went on to serve as a pastor at the Temple Street Congregational Church, where he and Lanson both advocated unsuccessfully for Black suffrage at a time when slavery was still legal in Connecticut.

Other students jumped from the 1850s to the present, filling the space in between. Jhonathan Uribe traveled to 1924, when Black musicians formed a chapter of the American Federation of Musicians to protect themselves from anti-Black racism and bias at the city’s thriving jazz clubs.

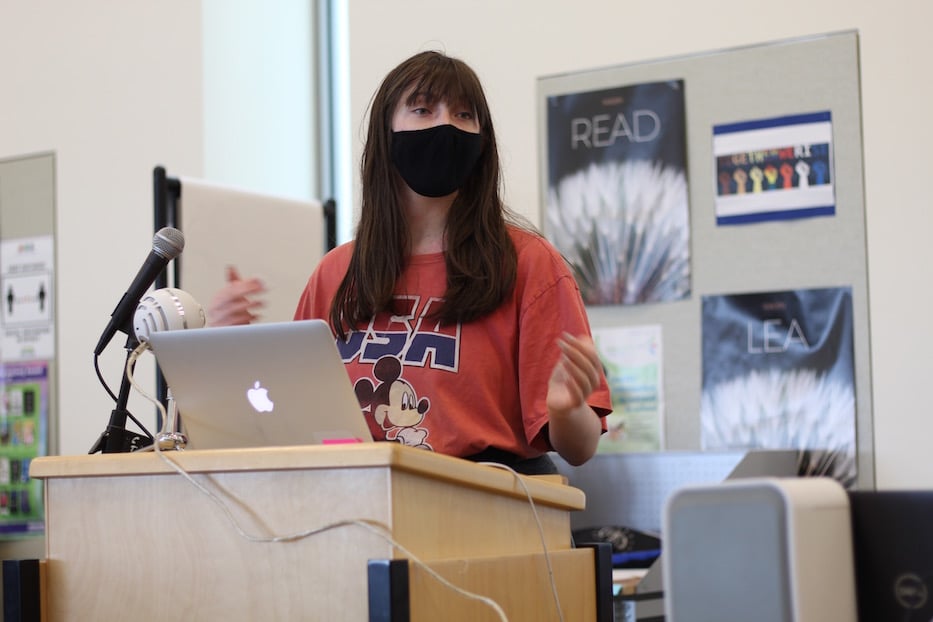

Lilly Centeno, who presented on the 1967 riots that broke out in the city's Hill neighborhood after a white restaurant owner shot and killed a Puerto Rican man on Congress. Her work of speculative fiction, "Breaking The Barriers," explored what would happen if families continued speaking their native languages in a country that made it illegal to do so.

Using an article from the New Haven Register, Lilly Centeno fast-forwarded to 1967, when a white restaurant owner shot and killed a Puerto Rican man on Congress Avenue. It set off four days of rioting in the city, during which Mayor Richard C. Lee imposed harsh curfews, and allowed police to arrest over 500 people. As Centeno spoke, it was hard not to think about hundreds of protesters gathered last year, pepper sprayed by police as they mourned the state-sanctioned murder of George Floyd.

Fifty-one years after the Black Panther trials first rocked New Haven, both Bedoya and fellow senior Davon Blackwell returned to those histories, unearthing a story of mutual aid and community care that is often wiped from history books.

Bedoya, who lives in New Haven, found archival photographs of the Panthers’ Sylvan Avenue headquarters, which opened in 1969. In one, a young Bobby Seale raises a microphone to his mouth under the word “Kidnapped.” Another exclaims: “Free Ericka Huggins!” in bolded print.

Bedoya said he became interested in the Panthers’ New Haven history after watching Judas and the Black Messiah earlier this year. When the character George Sams (played by Terayle Hill) mentioned New Haven, Bedoya “was astounded by it,” he said. He felt like he had to learn more. It led him to research the 1969 murder of suspected FBI Informant Alex Rackley and the Panther Trials of 1970.

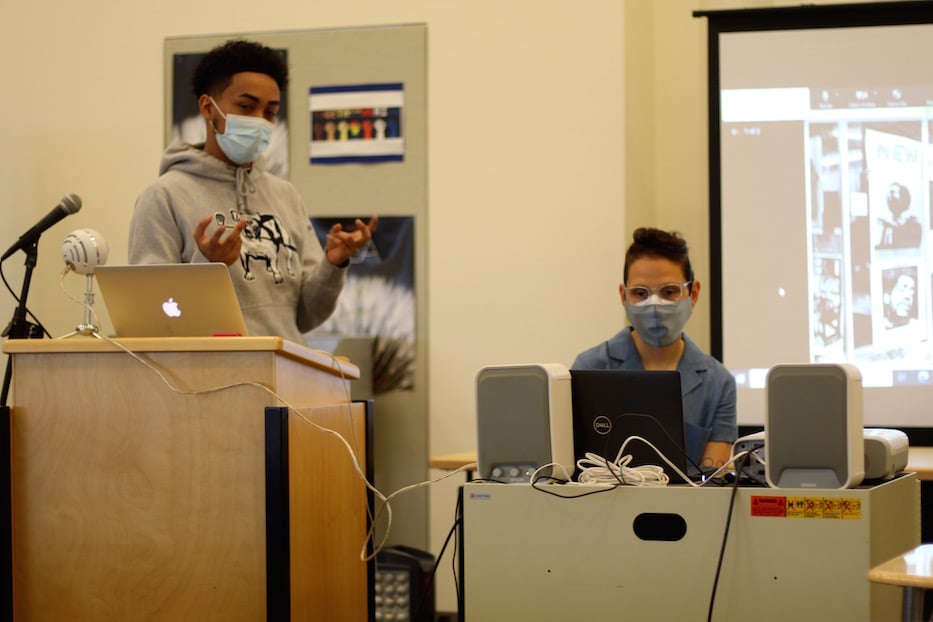

Davon Blackwell presents as Braginsky helps with tech.

Presenting during Braginsky’s second period class, Blackwell spoke on the Panthers’ free breakfast program in Newhallville. The more digging he did, the more he realized that the initiative hadn’t just happened in New Haven—it unfolded on Dixwell Avenue, just blocks from where he grew up and still lives. His grandmother participated in the program as a child. He plans on interviewing her this month.

“I was excited, but I was like—why are we not learning this in school?” he said after class. “It seems like something that is really important that happened in our history that we should know. There’s more stuff that we need to know about our history. There’s a bunch of stuff that’s hidden away that we all need to know.”

Braginsky often learns alongside the students. This year, Blackwell taught her that the federal government was so intimidated by the Panthers that it sent police to patrol the area, which deterred families from coming for free food.

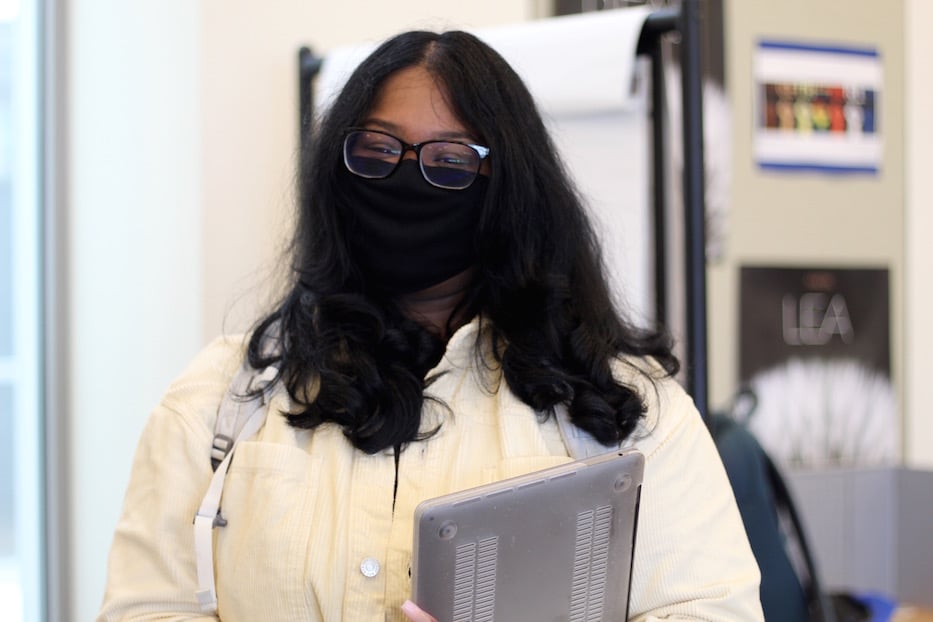

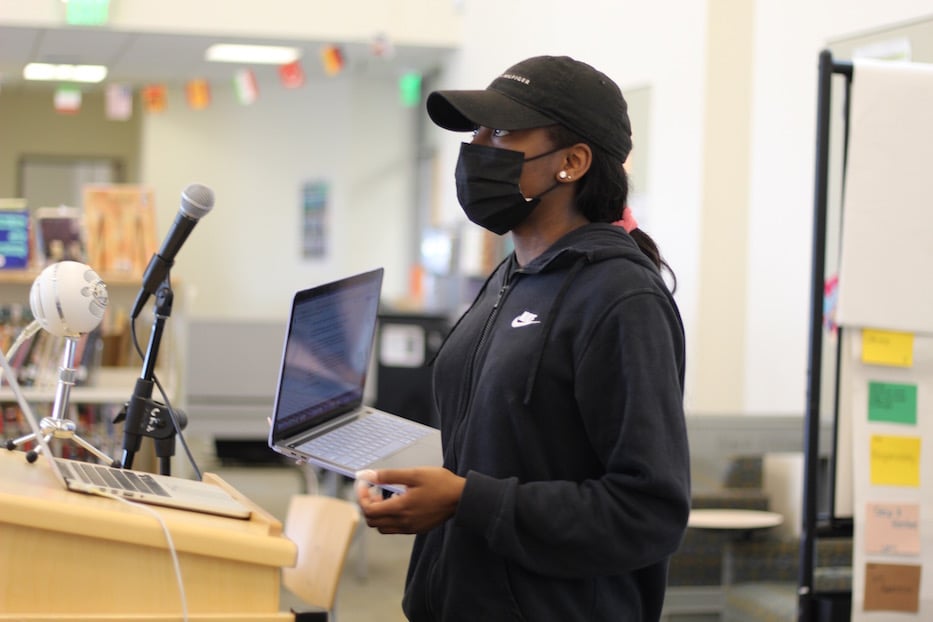

Jarelis Serra.

Students have also added events from the recent present, in a reminder that the map—and its history—is a living document. Jarelis Serra researched the labor strike at the Winchester Repeating Arms Factory that lasted from 1979 to 1980. A lifelong New Havener, Serra chose to take the class because it presented a different version of history than what she’d been taught over and over again in school. When she learned about Winchester in another history class, its history of racism hadn’t been part of the lesson plan.

“I’ve learned about Columbus so many times, and it’s like—it’s just boring,” she said. “I really want to know about my culture. I liked this class. I’ve always hated history, but this class, it made me change my mind on it. It made me understand my culture better … there was a lot of things I didn’t know about. I got to research a new history that’s not about white people.”

Chelsea Singh. Her work of speculative fiction, set in the year 2121, looked at what it would mean for skin color to no longer exist.

Closing the second section of the class, Chelsea Singh looked to the passage of a Civilian Review Board in January 2019, decades after police shot and killed Malik Jones in 1997. She focused on the longtime work of activists including Kerry Ellington and Ms. Emma Jones, Malik's mother.

Singh said she chose the topic because police brutality is not yet a vestige of the past—it pervades her present. One year after the legislation first passed, police shot and killed Fair Haven teen Mubarak Soulemane in West Haven. She said she still feels like people don’t know that the Civilian Review Board exists—which means they can’t advocate for its use.

“When it comes to the city of New Haven and the state of Connecticut, not everybody thinks that it happens here,” she said. “I think that that’s the case everywhere. Nobody thinks that it happens in their town, in their neighborhood … they kind of feel like it happens everywhere else. Especially in the inner-city towns, I feel it’s important to know that there will be a chance to have that kind of balance.”

Visioning New Haven’s Future

Bianca Osorio, who spoke on the history of Junta for Progressive Action. As a kid, she and her brother attended the organization's after-school programs. It was where she learned most of her Spanish, she said.

The histories are only part of Braginsky’s class. This year, students also wrote their own works of speculative fiction based on the novels of Octavia Butler, Daniel José Older, and Cherie Dimaline. Braginsky added the component when it became clear that “this school year would be unlike any other before.” In part, she credits writer-activist-dreamers Adrienne Maree Brown and Walidah Imarisha with the framing of the project.

Friday, students cracked open a series of worlds, all on the precipice of change. In her piece “Project Faded Planet,” senior Bianca Osorio envisioned a world not too different from her own, where a U.S. government-funded program looked for life on other planets. Earth, she explained, was no longer habitable because of climate change and human-made environmental degradation. So the government ran an exploratory program, preying on some of the country’s most vulnerable in its vision of intergalactic manifest destiny.

“The people who the government chooses are people of color and poor people because the government views them as expendable,” she read to knowing murmurs and echoes of U.S. Army recruitment pamphlets. “They don’t know what they’re getting into. They just know that the government is telling them that they’re going to be heroes.”

Until, that is, her protagonists Rosalie, Luciana, and Nathaniel started digging into the program’s true intentions.

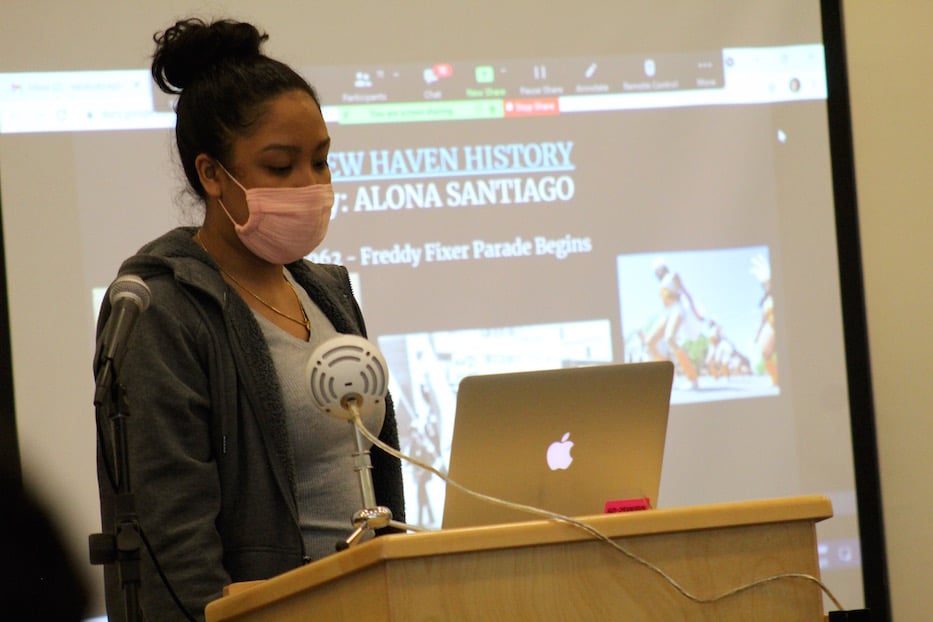

Alona Santiago traced the Freddy Fixer Parade from its beginnings as a neighborhood clean up in 1962 to today.

In a series of worlds that seemed not-too-far removed—robot police infected with malware, ongoing state-sanctioned violence, Gilead-like conditions for women, the suppression and policing of magic among girls and the echoes of the current Black Lives Matter movement—youth prevailed as problem solvers, time travelers, and alchemists.

Some, like Serra, saw a universe ready to reclaim itself from environmental degradation. Others, like Arella James, fight white supremacy with the power of mind-reading youth.

In her story “Assimilation,” Alona Santiago painted a chilling version of New Haven circa 2040. Imagine, she said: a New Haven scrubbed violently, strangely of Black families. Patrols of up to six police at a time watch each block. The Thompsons, who are Black, must stay in hiding to remain safe at all times.

When a Black man runs into the street “screaming for help,” matriarch Grace Thompson begins to uncover a history of state violence and disappearance that goes far deeper than she could have ever imagined.

Santiago said she came up with the idea while watching the rapid gentrification of the city’s Newhallville neighborhood, which threatens to displace families who have lived there for generations. “There are still Black people who live in the neighborhood, but a lot of Yale people are moving in,” she said.

Taliah Jennette, who spoke about the formation of the Native American Inter-Tribal Urban Council in 2010. It owes its foundations to former Connecticut NAACP President James Rawlings, who is both Black and an elder of the Wampanoag Nation.

As she spoke, her classmate Taliah Jennette said the word “Tulsa” audibly from where she sat in the library. Jennette later imagined a thriving New Haven in her story “Yale Goes Down!,” set just seven years from the present in 2028. In that world, a coalition of activists and city residents compel Yale University to pay taxes on its property, allowing for a city with vibrant, fully funded schools. It felt big, and possible.

“Watching students build these worlds against the backdrop of surviving senior year has been humbling and inspiring,” Braginsky said. “And a much-needed reminder that another world is possible, and young people will be the ones to build it.”

To view the map, click here.