Public art | Arts & Culture | Wooster Square | History | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism

Tai Olasanoye. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Dainty cups of tea were passed around in a mid-morning ritual. Ben E. King’s “Stand By Me" floated through the air, more voices joining in at the chorus. Nearby, a granite base sat without feet on its head for the second day in 128 years.

It was a gathering fit for a New Haven king—in a park that advocates hope will one day bear his name.

Friday morning, friends and members of The Lineage Group joined each other for a sit-in and history lesson honoring William Lanson, the formerly enslaved, self-emancipated, self-taught Black engineer responsible for Long Wharf, the now-razed New Guinea neighborhood, and sections of the Farmington Canal. The event was part of the group’s RevA.A.R.T.lution (Altruistic, Ancestral, Renderings Of Truth) initiative, run by Lineage Group co-founders Malcolm Welfare and Faith Lorde, as well as Ricquel Pratt and Steve Nardini.

It doubled as a chance to honor Nate Blair and Los Fidel, both of whom were physically attacked by pro-Columbus protesters on Wednesday morning, as the statue of Christopher Columbus came down after 128 years.

| Malcolm Welfare and Ricquel Pratt. |

Welfare organized the event after watching live streamed footage of the two being assaulted. He said he felt unease, and then deep fear and frustration, seeing racially-motivated violence unfold in his home city. An educator and artist—in addition to the Lineage Group, he is a teacher at King Robinson School—he wanted to take the opportunity to set the historical record straight.

"I was just floored and jarred with energy that reminded me of Civil Rights-era, Jim Crow-era terror and fears,” he said. “I was inspired to do something. I wanted to do something for my community to show how we can create a space of equity.”

The proposal to rename the park joins in-progress efforts of New Haven’s Amistad Committee and City Plan Commission to complete a sculpture and William Lanson Memorial Plaza closer to the Farmington Canal. Onyeka Oboicha, who lives nearby on Chapel Street, has also drafted a resolution and co-written an op-ed in favor of renaming the park.

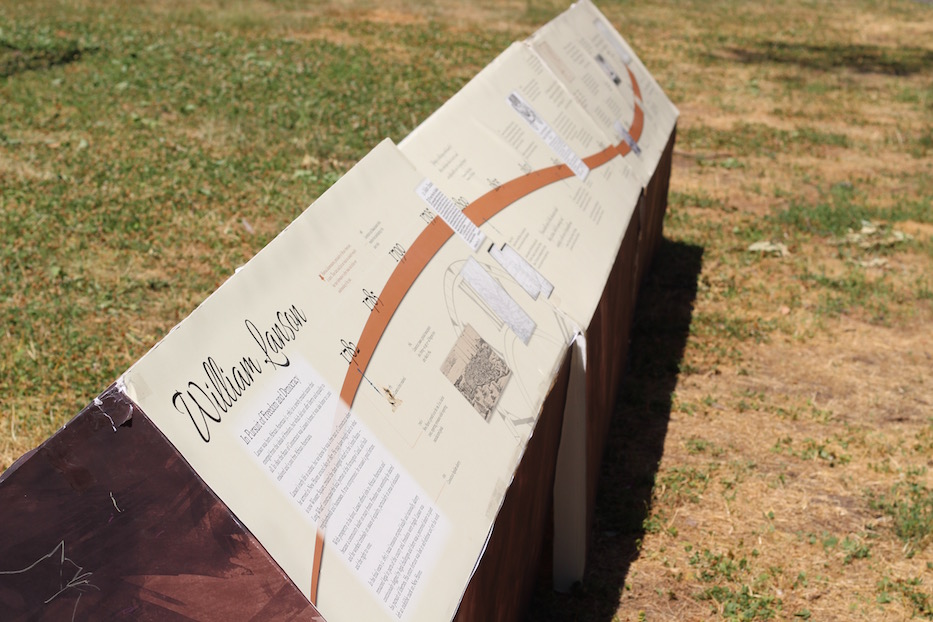

A little after 10 a.m., Welfare and Nardini set up a three-part timeline, panels fixed to a display that looked like a long line of miniature, brown-brick row homes. On the panels was a detailed history of Lanson’s life, work in engineering, and descent into poverty as white New Haven encroached on and bought his land. Welfare credited Stetson Branch Manager Diane Brown for loaning him the panels, which she uses as a teaching tool when the branch is open to the public (it has been closed due to COVID-19 since March).

“This is so that people can understand history,” Welfare said.

The history is one still not taught in New Haven classrooms. After escaping enslavement and arriving in New Haven, Lanson was hired as a project superintendent on the city’s then-nascent Long Wharf, a position through which he extended the wharf by almost 1,500 feet and thus solidified the city’s ability to smoothly do trade. He also built part of the retaining wall on the Farmington Canal Heritage Trail, which is still used today.

Lanson believed in integrated neighborhoods, at a time when New Haven was actively contributing to chattel slavery through both the sale of humans (the city’s last documented sale of Black people into slavery took place in March 1825, according to records kept by the New Haven Museum) and inventions like Eli Whitney’s cotton gin.

He bought land that became the city’s then-dubbed New Township neighborhood, located just to the east of what is now Wooster Square around Franklin Street. He sold to free and formerly enslaved Black Americans as well as white people. He also owned stables, operated the Liberian Hotel, and co-founded the Temple Street Church, now recognized as the Dixwell United Church of Christ.

| Fidel atop the former statue's base. |

In the 1830s, new racial tensions took hold of the neighborhoods Lanson had come to call home. The area was purchased by white New Havener Matthew Elliott, who built homes over what had been New Township. The great engineer, responsible for parts of the city’s literal foundation, died in poverty in 1851.

“As educators, it's our duty to keep the community knowledgeable about the different things that are going on,” said Pratt, who is a guidance counselor. “He [Lanson] started this. Why not educate the people that are around, and let them know that before it was Wooster Square, William Lanson was right there, building up this space.”

Around her, walkers, Wooster Square neighbors, and parents with young kids entered the park, spotted the display, and took a few minutes to read it. On a shaded patch nearby, Blair arrived, spread out a blanket and unpacked a tea set and several bags and containers of loose leaf tea. He began to steep and pour, talking about Wednesday’s events while performing alchemy.

| Blair. |

After five years living in the neighborhood, he said he finally feels safe and welcome walking around the park. He joked that he’s long been advocating for a stately statue of Frank Pepe, leaning down just a little over a perfectly cooked New Haven pie, instead of someone who raped, murdered and enslaved millions of Indigenous people. As if on cue, a 204 bus trundled up Chapel Street and let out a stream of honks in support of the group.

“The fact that people are coming to defend Columbus in my neighborhood means that they're defending white supremacy in my neighborhood,” he said of Wednesday. “And like, this isn’t New Haven. These aren’t the people of New Haven. New Haven has its problems, but not like that. I felt pretty safe coming down here [Wednesday], honestly. I had faith that people would show up and I wouldn’t be the only one there.”

Fidel, who was punched twice on Wednesday morning, arrived and took a seat next to Blair. He recalled that on Wednesday, he had joked with his dad that he might get jumped by a bunch of angry white people. He had been kidding. Then it happened.

| State Rep. Roland Lemar, who watched Wednesday's events for hours, with Fidel. |

“I tried to converse with them and I tried to educate them on how this statue makes me feel,” he said. “Now, I’m not about erasing their history. If that means a lot to you, that’s what’s up. Put that shit in your house and praise it. Put that shit in a museum and praise it. But I don’t want to see it.”

As more attendees took a seat in the circle, they dipped into a discussion in reeducating New Haveners on the history of race and racism, undoing white supremacy, and weaving the history of Lanson into the park. On the far side of the group, lifelong New Haveners Brandon Lawrence and Celina F.A. (she asked that her full last name not be used) said they are in full support of renaming the park.

Neither of them were able to make it on Wednesday, and arrived Friday to reclaim the space with peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and ziplock bags of pistachios and fresh strawberries. They said they wanted to get a crash course in Lanson, whose name had never come up in their time as students in the city’s public schools.

“Rename it please,” Lawrence said. “I support the renaming wholeheartedly.”

| Brandon Lawrence and Celina F.A. |

F.A., who is preparing to start graduate courses in social work, said she also wanted to celebrate: she’d watched Wednesday’s events on WTNH’s website and still felt overcome by emotion two days later.

“I pass white, but I’m half Mexican on my dad’s side and Puerto Rican on my mom’s side,” she said. “I told Brandon, ‘get the tequila, get the rum.’ We took shots. It was honestly very joyous and honestly, for me, a very emotional moment.”

F.A. grew up in New Haven and attended Worthington Hooker School as a kid. When her dad saw how little of her own history she was getting, he gave her a copy of Carlos Fuentes’ The Buried Mirror, through which she learned about the rape and genocide that accompanied colonization. She later learned about the history of Italians too, including the fact that the Columbus mythology was part of their assimilation to whiteness in America.

“This is a way for us to really come together, and say, look: we’ve been oppressed not in the same ways but in different ways, and we can find these moments to grow together and heal together,” she said. “As a community.”

Winter Carson and her 4-year-old son Logan L.

Back at the display, Brett Hoover leaned over the history, reading it paragraph by paragraph. A digital strategist for New Haven Promise, Hoover lives on one side of the park, and walks there multiple times a day for exercise. He said he doesn't know much about Lanson—but would like to see him getting his due around town.

“I don’t want to see anything done that people would think is disrespectful or anything, but right now it’s just Wooster Square Park, in Wooster Square,” he said. “Might as well be Lanson Park in Wooster Square, and let people know who he is. That’d be wonderful.”

Further down the display, Winter Carson and her 4-year-old son Logan L. looked over the history. Welfare stepped in as their guide. He leaned down to Logan to talk about a picture of the Schooner Amistad, in which he had taken a particular interest. On the timeline, it sat squarely in a small circle, bouncing on foamy blue waves.

“What’s the name again?” he asked. “A-mi-stad. Say it one more time.”

| Jensen Davila and Pratt. |

Jensen Davila, who grew up in the Church Street South apartments, said he was excited at the prospect of Lanson Park. As both a dad and a Puerto Rican, he wants his kids to grow up knowing a complete history of New Haven and the United States, including the people of color who built its foundations and then were erased from the historical record.

“I always try to tell people, like, racism is something that, it’s kind of like anger toward somebody, or maybe you’re scared of that person,” he said. “But it’s not, something real. You’re just scared of somebody else.”

Nearby, educator Tai Olasanoye had taken out his guitar and started to play Green Day’s “Boulevard Of Broken Dreams” and Ben E. King’s “Stand By Me.” Earlier in the day, he had joked that Rocky Balboa would make a more fitting presence than Christopher Columbus. Now, he strummed softly. When he realized he didn’t have the lyrics to the second tune, he asked other attendees to join in.

Phones came out. Voices rose, carrying the lyrics—So darlin', darlin', stand by me!—across the space. For Olasanoye, it was also a reclamation: he had come Wednesday after seeing Blair and Fidel get beaten up. Moments after he played for the group, Fidel climbed onto the statue’s base, which is now empty.

“I think the community can come up with something that’s a way better representative of what America should be,” Olasanoye said.

Back at the display, Welfare said that he plans to keep going with the proposal to rename the park. He said that he will be talking to both the Amistad Committee and Board of Alders in the weeks to come.

“That’s what I want to see,” he said. “Conte School. Wooster Street. And Lanson Park.”