Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | WNHH | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism | Metropolitan Business Academy

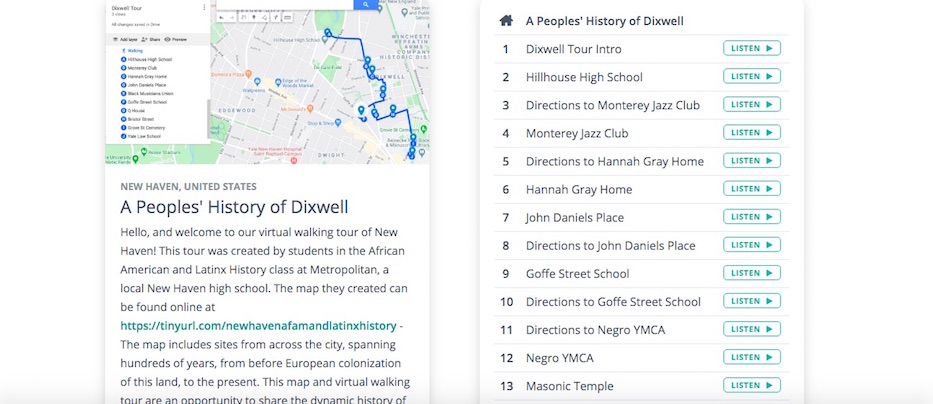

| Screenshots from A Peoples' History Of Dixwell. |

Just past the intersection of Goffe and Crescent Streets sits James Hillhouse High School, a large brick building with an attached athletic complex. Even after months of distance learning, the building is full of recent memories: cacophonous sporting events that are now missed and mourned, a production of The Wiz that was cut short by a global pandemic, a socially distanced graduation that still had students cheering.

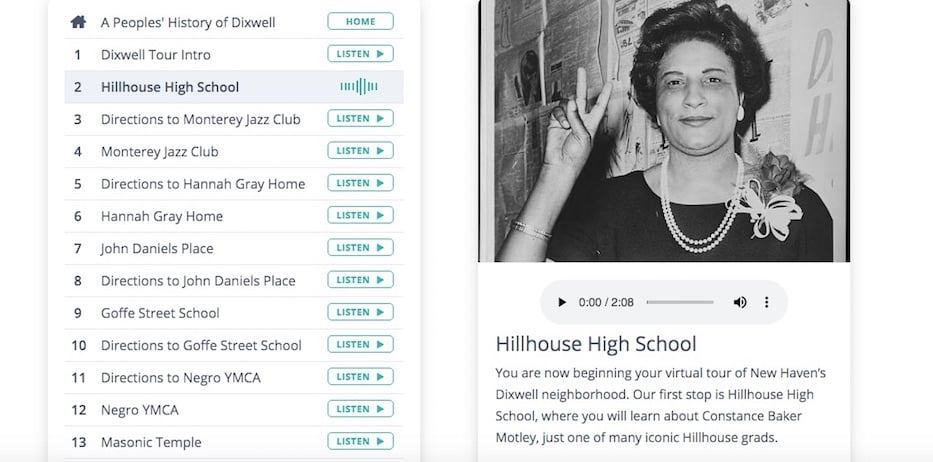

But how many New Haveners know that it also graduated Civil Rights icon Constance Baker Motley, the first Black woman to serve as a federal judge? That long before working with Thurgood Marshall on Brown v. Board of Education, long before representing Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1963, she travelled the 19 minutes from her home on Garden Street to the school each day?

Students are filling in those gaps on A Peoples' History of Dixwell, one of two new virtual walking tours from an African-American & Latinx History class at Metropolitan Business Academy. Another, A Peoples' History of the Hill, is also available online. The two were produced with help from Tiffany Stewart and Donnell Durden of Aligning and Metropolitan Business Academy teacher Nataliya Braginsky.

“People who may have thought they would be forgotten throughout history … I’m glad we are bringing them back to the surface and showing what they have done,” said Metropolitan grad Dameon Dillard, who worked on the project, in a recent interview on WNHH Community Radio’s “Arts Respond” program. “I think it’s great exposure to people.”

Voices on the virtual tour include Dillard, Angel Rovira, Darlaney Chanthinith, E’moni Cotten, Flor Jimenez, and Kaleeah Ramos. But the group effort is much larger, born out of months of work mapping the city’s history, learning about redlining, borders, migration, revisionist histories, and creating a virtual, interactive walking tour earlier this year.

The project began in earnest last year, after students across the state traveled to Hartford to testify on behalf of H.B. 7082 and H.B. 7083. The two bills, backed by Bloomfield and Windsor Rep. Bobby Gibson, called for the addition of African-American and Puerto Rican history courses in Connecticut public high schools. Advocates included New Haven-based Students for Educational Justice and Citywide Youth Coalition, as well as Hearing Youth Voices and CT Students for a Dream.

By the time the legislation was passed, it included Black, Puerto Rican, and Latino history more broadly under its umbrella. As recently as June, the New Haven Educators’ Collective called for that teaching to extend to all K-12 schools in the state.

In her classroom, Braginsky began teaching the state’s first course on African-American and Latinx history in fall 2019, sourcing student input on everything from the course’s language to pieces of its curriculum. Cotten recalled students telling her that “we want to be taught the victories, the good things that we did” after years of education in which Black history began with enslavement.

The class began with intellectual and cultural history of the African continent before ever discussing enslavement. It traveled to the Americas before talking about European colonization. Then it reached American and local history, pushing back against the white lens with which it is often taught. Braginsky said that beyond a non-racist educational lens, it was important for her to use a collaborative, anti-racist educational lens.

“We do a lot of talking about dominant narrative versus counter narrative,” she said Friday, as a pattern of red-orange fish swam across her shirt. “Students can analyze what’s being presented to them and what has been taught to them in those terms.”

“We live in a racist society, right,” she later added. “Racism is embedded in all of our institutions, including education. And if we say, ‘Oh, I’m not racist,’ it’s like we disavow that, as if we have no role in it. As if we don’t benefit from it and aren’t oppressed by it. And we are all affected by it in different ways. And we have to admit it exists before we can do any of the work to dismantle it.”

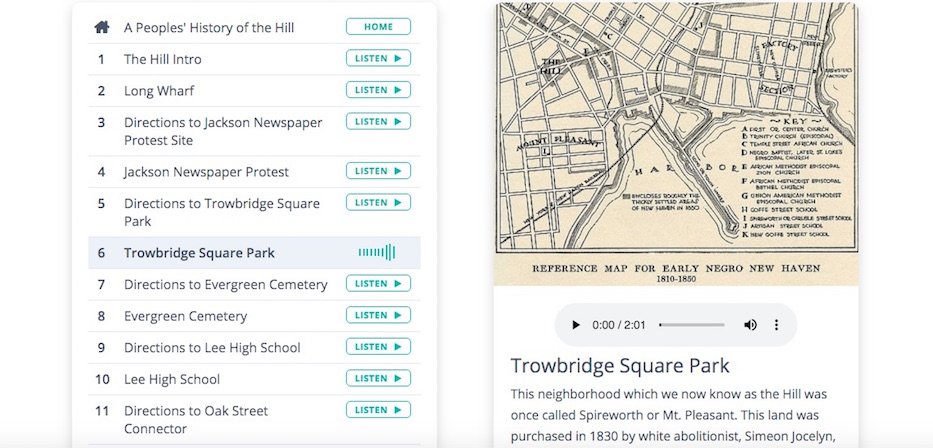

In the late fall the class started building a map of the city’s Black, Latinx and Indigenous history, with sites that dated back to New Haven’s pre-colonial roots and paid homage to Quinnipiac land. Braginsky urged students to identify places that were both personally and historically significant to them, from the Amistad Memorial downtown to the Monterey Jazz Club on Dixwell Avenue to the New Haven Green, where Connecticut Students for A Dream held a summit in 2017.

As the project developed, sites multiplied across the city. Downtown, walkers can now acquaint themselves with the old bones of The Artisan Street Colored School, built as New Haven’s first Black school in 1811. At City Hall, they can check the map to learn about the Elm City ID Card instituted under Mayor John DeStefano.

They might stop at the former home of the Temple Street Congregational Church, where a hot pot restaurant and parking garage have erased a history of abolitionist thinking. Or make it to Grove Street Cemetery, where William Grimes, Mary A. Goodman, and abolitionist Ebenezer Bassett are all buried, along with Black veterans of the Civil War.

If they venture into the Hill, they can walk along the headstones in Evergreen Cemetery to find the graves of physicist Edward A. Bouchet, the first Black person in the U.S. to earn a Ph.D., and Lt. Augustus Rodriguez, a Puerto Rican who fought in the American Civil War. Or, nearby, the former grounds of Lee High School, where freedom rider Lula Mae White taught for almost three decades after graduating from the school herself.

“I’ve for a long time had a dream of creating a space where young people can actually be the experts of their own cities and their own histories, and actually can be paid to be tour guides,”Braginsky said. “People come and visit, New Haven has a lot of tourism. I think that young people should get to be the ones who tell the story of New Haven. And I think that, that can be a really radical act in the way that education can. Especially when young people, especially when youth of color, are the voice of that.”

For many of the students, it was a revelation. Dillard moved to New Haven when he was just a kid, after his family was displaced from Louisiana by Hurricane Katrina. He’s spent most of his life in the city’s Hill neighborhood, where the history of Black labor, the Great Migration, and integrated neighborhoods runs deep. But the Black history in his classes was lacking: before getting to Metro, he learned about Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Rosa Parks, and very little else.

“Every Black history month, we learned about the same three people,” he said. “And it got kind of frustrating, because there’s way more people who’ve done just as important things in history, and we don’t know nothing about them. I just feel like that’s kind of sad.”

Dillard gravitated toward the city’s music history, which pumps through its 18.7 square miles still today. He recalled his excitement when he learned that The Five Satins recorded their hit, “In The Still of the Night,” in a church basement on Townsend Avenue in 1956.

Cotten, who is headed to Howard University this month, said she was also excited by what she and her classmates uncovered. A resident of the city’s Fair Haven neighborhood, Cotten grew up learning “that Yale is what made New Haven, not the other way around.” The project reframed the way she thinks about the city, she said.

Initially, she chose to research Bregamos Community Theater after three years of working with its founder, Rafael Ramos. She praised the class for helping her learn about not just the recent history of social justice theater, but also jazz clubs, schools, and historic homes that are no longer standing, and the Indigenous land on which New Haven is built.

“A lot of people didn’t even know that certain things existed before slavery, but there was so much to us before that,” she said. “There was so much to the Native Americans before Columbus came, or before anything. So just to learn about that side was really nice.”

In March, in-classroom mapping was cut short when schools closed due to COVID-19. But Braginsky and students kept the project going: research continued at kitchen tables, desks, and laptops. After connecting with Aligning, six members of the class recorded tour stops in their bedrooms and closets, often beneath blankets and layers of clothing.

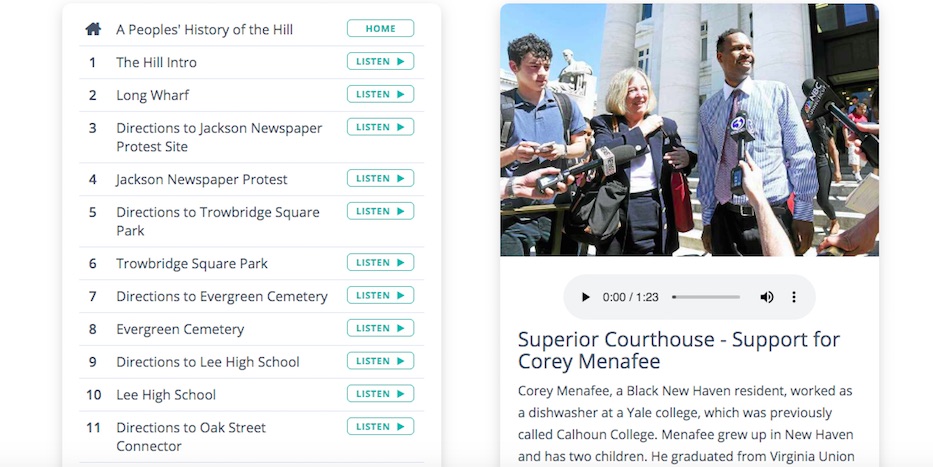

Cotten laughed remembering the feeling of putting a blanket over her head and recording multiple takes. For the tour of Dixwell, she added research on a second site: Grace Hopper College, which was renamed after Yale dishwasher Corey Menafee smashed a panel depicting enslaved people holding baskets of cotton on their heads. Menafee's action led to months of protests and community organizing before the Yale Corporation agreed to change the name.

The college was previously named after John C. Calhoun, a graduate of the university and ardent defender of slavery for whom Yale named a college in 1930 in an attempt to draw Southern students. In working on that history, Cotten and her classmates also learned that New Haven was home to a might-have-been HBCU, which was largely blocked by the university to effectively protect slavery and segregation in the 1830s.

“I bet a lot of people didn’t even know that Calhoun was racist, or that the name was changed to Grace Hopper,” she said, later adding that there’s a good chance she’d be staying in New Haven if it had an HBCU. “But now, if you listen to the podcast, now you know.”

Dillard, who will be attending Alabama A&M University in the fall, added a stop at the New Haven Superior Courthouse, where the murder trial for Black Panther members Bobby Seale and Ericka Huggins was held in May 1970. Seale and Huggins were ultimately acquitted of the charges, which included conspiring to kill Black Panther member Alex Rackley, who was a suspected FBI informant.

“I’m really interested in learning a lot about my own peoples’ history and all that,” he said. “It was good to see that New Haven actually had a good, like, a good stand for rights. And not just people in New Haven. I’ve seen that Yale students actually helped the Panthers, that they came over and gave them food, shelter and all that. It’s good to see that New Haven—even though now they’re doing the protests and all that, they’ve always been helping out in the political struggle.”

Going forward, Dillard and Cotten said they hope students keep adding to the map, with current events including the removal of the Christopher Columbus statue in Wooster Square in late June. There are new pieces of Black and Latinx history coming into the city: in September, sculptor Dana King is set to unveil a larger-than-life statue of William Lanson on the Farmington Canal.

A new skate park, spearheaded by two young Black skateboarders and Dixwell Alder Jeanette Morrison, is almost finished at the northeast edge of Scantlebury Park. The new Q House, with a renovated Stetson Library, is poised to open in March 2021. Just a few blocks away in Newhallville, new, bright murals sit on the Learning Corridor and a garden blooms across the street. On Goffe Street, not far from the Hillhouse High School, Love Fed Initiative has started a movement to end food apartheid in New Haven, directed especially towards the city’s Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) residents.

Braginsky added that she’d like to see an addition of oral history, from many of the city’s elders whose stories may not yet be written down or recorded anywhere.

“Outside of myself and the people that I know, I’m just happy that these historic people are getting put on the pedestal that they deserve,” Cotten said. “Their history should have been taught to us a long time ago. Especially growing up in New Haven. I have been in New Haven Public Schools since I was in third grade, and it didn’t [have to] take until high school to learn about these people.”

“Even though it happened late, better late than never,” she added. “Now I get to help other people get exposed to the same history—to the important history. To the history that made our city what it is today.”

Listen to A Peoples' History Of Dixwell here. Listen to A Peoples' History of the Hill here. To listen to or download the full interview, click on the Soundcloud link above. "Arts Respond" is a collaboration of WNHH Community Radio and the Arts Paper.