Culture & Community | Education & Youth | Immigration | Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services (IRIS) | Refugees | Arts & Culture | Wilbur Cross High School | Arts & Anti-racism

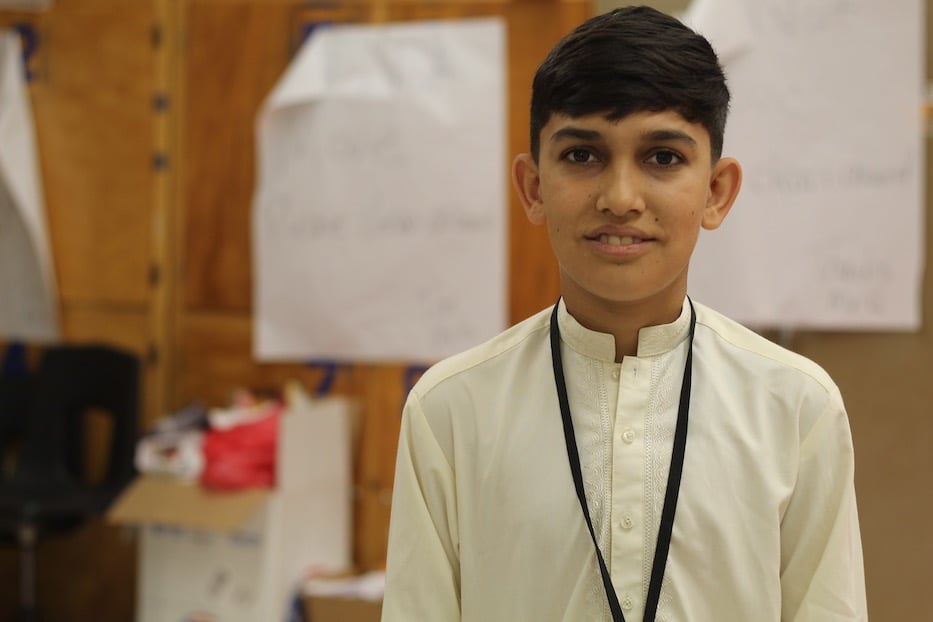

Abdul Wahab. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Thirteen-year-old Abdul Wahab stood in front of a table covered in ceramics, taking in each piece one by one. A green bird perched on a branch, looking out into the classroom. A cat curled its thick tail toward the ceiling, a patch of white fur running along its neck. A lemon-yellow chair stood sturdily on its four legs. He reached his own, a miniature water jug in bright orange glaze, and let him transport it back to a more peaceful time in Logar Province, Afghanistan.

This year, Abdul is one of over 140 students in Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services’ (IRIS) Summer Learning Program (SLP), an extension of the school year meant to teach English and grow social and emotional skills for young immigrants and refugees. For six weeks, it has also worked to teach tolerance among both students and staff alike with a new focus on Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI).

As in years past, it takes place at Wilbur Cross High School, which is close to IRIS’ New Haven offices on Nicoll Street.

Together, it combats what is commonly called the “summer slide,” or the learning loss students experience when they are out of school between June and August. In the classrooms, that has looked like everything from mapping New Haven to the universal language of Uno. Last week, it included close looking sessions in a student art gallery, a celebration with Syrian food and flag-topped cupcakes, and a multicultural dance and music program that helped bring the summer to a close.

A display that IRIS After School Coordinator Gladys Mwilelo called "A Gift From Home"

“This year, we really worked to incorporate a curriculum for English language learning and more social and emotional learning with getting to know the different cultures [represented],” said Imani Jean-Gilles, education programs coordinator at IRIS. “Students are learning more about each other’s experiences. We are really trying to build respect.”

Started in the early 2000s to accommodate a growing number of young arrivals, SLP has since become a trademark of the work IRIS does, which ranges from statewide refugee resettlement, education and job training to advocacy on the state and national level. Many of the teachers, two of whom are placed in each classroom, are SLP alumni, who bring their own stories of migration with them each time they teach. Students, meanwhile, range from preschool to high school, with some who have only been in the U.S. for a number of months.

This year, new and returning students represent over a dozen countries, telling a story of migration and conflict that has criss-crossed the globe. In addition to Afghanistan, which accounts for 60 percent of young arrivals in the program, students hail from Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Venezuela, Syria, Senegal, Sri Lanka, Ukraine, Colombia, Angola, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

On a given day, it’s not uncommon to hear Farsi, Spanish and Kiswahili mingling in the hallways, or strains of Arabic flying from one classroom door to another.

IRIS After School Coordinator Gladys Mwilelo, who came to New Haven as a refugee.

On a recent Wednesday, the first floor of the building filled with chatter as students and teachers buzzed from classroom to classroom to view each other’s final projects. At the end of one hallway, IRIS After School Coordinator Gladys Mwilelo welcomed them to an “Art Gallery,” her smile bright as she raised both hands, stretched her fingers all the way out, and started with a speech she’d already done four times that morning.

“Listen!” she said, students falling to a hush each time. “Before you go to each table, there is one rule. No …”

“Touching!” a young student cried back from a kindergarten-aged class.

“Touching!” she answered back. She gestured to tables across the room, where students had created sculptures, drawings, and paintings that reminded them of home. In every creation, she could see something of her own New Haven story, which is still evolving.

A refugee from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mwilelo came to New Haven with her family in 2013, after years in a refugee camp in Burundi. With IRIS’ help, she learned English, started her high school studies at Wilbur Cross, and went on to study communications at Central Connecticut State University. When she graduated, her work ultimately led her back to IRIS.

It’s a full-circle sort of moment: SLP and IRIS' Young Leaders Program is one of the places her life in New Haven began. Now she works closely with students in whom she can see her younger self.

That includes relatively new arrivals to the U.S., who are still navigating a new home as they try to stay connected to the customs and traditions of their first one. Watching as Abdul glided over to his inches-high water pot, Mwilelo offered up the title “A Gift From Home.”

For Abdul, now a rising eighth grader at Harry M. Bailey Middle School in West Haven, the suggestion fit. Born and raised in Logar Province, Afghanistan, his family fled the country in 2022, and spent nine months in Dubai before coming to the U.S.

Beyond his parents and siblings, many of his family members are still in Afghanistan. In the midst of a completely new normal, art making helps him relax.

“I like it here but miss it,” he said of Afghanistan. When given a prompt and some clay in SLP, he immediately thought of the pots that his family used to collect and store water.

Ahmad Al-Zouabi (with flag around his neck).

Nearby, lead teacher Ahmad Al-Zouabi looked over a table of paintings, studying a pair of ripe cherries on a polka-dotted pink background. A rising sophomore at the University of Connecticut, Al-Zouabi came to the U.S. from Syria with his family in 2016, and found a community among other young refugees at IRIS as well as the students he met in the New Haven Public Schools.

While he is studying chemical engineering in college, “I wanted to give back” during the summers, he said. SLP, which helped him adjust to life in New Haven, was like coming home.

“I just felt like, through IRIS, I can help someone who is in my place now,” he said. Hours later, an audience member could see him dancing out that mission as he led students in Dabke, a form of Levantine folk dancing that helps him keep his ties to Syrian culture alive.

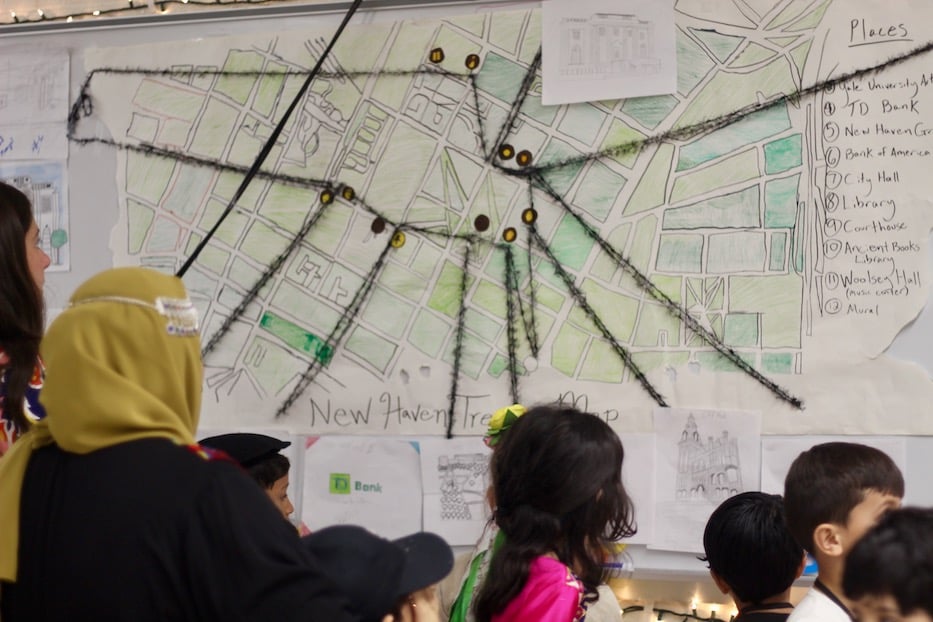

Down the hall, a burst of laughter escaped from a classroom where high school students were showing off an illustrated map of downtown New Haven. Inside, friends Zahid Mangal and Olfat Ibrahim pointed out each location to their peers, tracing a path from the New Haven Green and U.S. District Courthouse to a mural of Sun Ra in the Ninth Square.

Both recent arrivals from Afghanistan—the two are now classmates at James Hillhouse High School—they said they enjoyed getting to know the heart of the city, with favorite stops inside the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library and City Hall. Beneath the map, hand-drawn renderings included definitions written in both English and Pashto. A courthouse is an institution that the government sets up to settle disputes through a legal process, read one.

Nearby, student Muslima Mangal (who asked not to be photographed) said that she loved the program’s field trips, which took students downtown to orient them with City Hall, the New Haven Free Public Library, U.S. District Courthouse, and Yale Art Gallery among other buildings. On the map, she and her peers displayed how major arteries snake out from downtown to the city’s different neighborhoods, the roads displayed in wiry black yarn.

A student at James Hillhouse High School, she said that art is her favorite class, because it helps her relax. Mapmaking felt like an extension of that work—with a side of civic engagement folded right in. “It lets me express myself,” she said, speaking in Pashto as her friend Hkula translated.

As they studied their handiwork, another group trickled into the room, and came in close to the map. A classmate wrapped in the Guatemalan flag looked up and smiled. Downtown New Haven had never looked so good.

“I Feel Confident. I Feel Strong”

Imani Jean-Gilles and Hancy Michaud.

Back in a classroom that IRIS has snagged as its de facto office and “Debrief Room,” Jean-Gilles unveiled hundreds of cupcakes that she had baked the night before, sending the smell of spun sugar and vanilla beans into the air. Atop each, tiny toothpick flags turned them into a miniature United Nations, with bright bands of color that stretched across each container. A few feet from where she worked, students and teachers played a game of Uno, cards furtively fanned behind their palms.

For Jean-Gilles, the child of Haitian immigrants, the program is a natural extension of work she’s been doing for decades. Growing up in Bridgeport, her parents were “very, very proud to be Haitian,” and made sure they passed it down to their daughter. From an early age, she knew to correct people if they mispronounced her last name, or didn’t bother to learn it in the first place.

“They taught me never to acquiesce to what people think you should be,” she said. It instilled in her a mission to advocate for and champion the rights of those coming from similar backgrounds.

When she started her studies at UConn, Jean-Gilles started volunteering at the Bridgeport-based Connecticut Institute for Refugees and Immigrants (CIRI) and found that she loved the work. After graduating, she worked with the organization Seeds of Peace, doing conflict resolution with students from the Middle East, and as an Americorps member with Catholic Charities.

She started running the Summer Learning Program three years ago, when students were still masking up and trying to social distance as they navigated life in a new country. There’s a sort of mirror there, she said: Haitians live with a history of displacement, colonization, and diaspora that is also true for so many students who come through the program. It’s also why she implemented a DEI practice this year, after noticing that students sometimes judged each other—and their new classmates—based on where they were from.

None of it happens in a silo, she was quick to add: many of the program’s teachers are fluent in multiple languages, and have a mix of foreign teaching experience and lived experience as a refugee. “To me, it’s important to have that diversity” in the classroom, she said. While over 140 students registered for the program, roughly 100 are in the building each day.

As if on cue, she paused to pick up her cell phone, and flowed easily between English and Haitian Creole as she tried to arrange an Uber for Hancy Michaud, a Brooklyn-based Haitian drummer who was coming that afternoon. For a moment, teacher Fatima Momand poked her head in to see what time lunch was set to arrive, and found at least three different conversations all going on at once.

Now a student of health and science at the University of New Haven, Momand grew up in Kabul, then came to Maryland with her family in 2014. For a time, she said, it was safe enough to return to Afghanistan—and her family often did. Then in 2017, they came to New Haven for good.

One of six siblings, she came back to IRIS to nurture students who remind her of where she’s been, Momand said. By the time she entered Hill Regional Career High School, women and girls in Afghanistan were struggling to get the educational resources they needed. When she headed to college, women were barred from schools and universities. In Connecticut, she said, she has the academic freedom to pursue her dream of becoming a doctor.

“I do miss home but I don't miss the situation going on,” she said. “I feel free—independent. I feel confident. I feel strong. I can do what I want for work.”

Like many of her peers Wednesday, she took the time to pay homage to home with her outfit, a Cerise-colored, silky pink and blue dress that matched her hijab, and came with sequins and rich embroidery. Her beaded slippers, the color of coffee with cream, were a find from the internet.

Around the hallways, she was in good company: students came wearing flags like superhero capes, with wreaths of dried flowers perched atop their heads, and in traditional vests and dresses from Syria, Afghanistan, and Egypt. As they trickled into the auditorium for a final performance of the day, the outfits created a rainbow of color, students bouncing with as excitement as they found their seats.

“I Hope You Are Proud Of Where You Come From”

Students dance.

They didn’t have long to wait. On stage, Michaud welcomed them with the drums, the sound ringing across the auditorium. Born in Haiti and now a sound technician and working musician in Brooklyn, he eased into a heartbeat-like rhythm, the whole room falling to a hush around him. Even in their seats, students moved along, their heads and shoulders rocking with each touch of palm to drum skim.

He rose to flip on Eddy François’ “Moise Dezo,” and began drumming over the recording of handheld shakers and François’ steady voice. In the audience, some students clapped along; others watched, simply spellbound. When she rejoined him onstage, Jean-Gilles was beaming.

“You guys are so beautiful in your outfits,” Jean-Gilles said as she looked out over the auditorium, and nine dozen faces looked back. “I hope you are proud of where you come from.”

And for the rest of the performance, they were. As dancers linked hands and took the stage for the Dabke, they were jubilant, gathering height as the music swelled around them and they leapt up. When several returned for the Attan, a traditional dance of Afghanistan, they channeled a history that was thousands of years old.

Nowhere may it have been as fresh as in a performance from Anna Yuziuk, who arrived recently from Ukraine, took the stage. As she began to sing “Oi u luzi chervona kalyna,” she shifted nervously in place, moving from one foot to the other. The music, flowing from a nearby speaker, threatened to swallow her voice. Watching from the audience, proud dad Ihgor Yuziuk, knew exactly what to do.

Yuziuk bounded up the steps to the stage, wrapping his arms around Anna. He joined in the lyrics as if they were second nature: Ой у лузі червона калина похилилася/Чогось наша славна Україна зажурилася (“In the meadow, there a red kalyna, has bent down low,/For some reason, our glorious Ukraine, has been worried so.”)

Beneath his outstretched arm, Anna’s voice rang through the mic, clear as a bell. А ми тую червону калину підіймемо,/А ми нашу славну Україну, гей-гей, розвеселимо! (“And we'll take that red kalyna and we will raise it up,/And we, our glorious Ukraine, shall, hey - hey, cheer up - and rejoice!”)

They finished in an embrace. The crowd burst into applause, and the show went on.