Dance | Education & Youth | Music | Arts & Culture | Westville | Education | Davis Street School

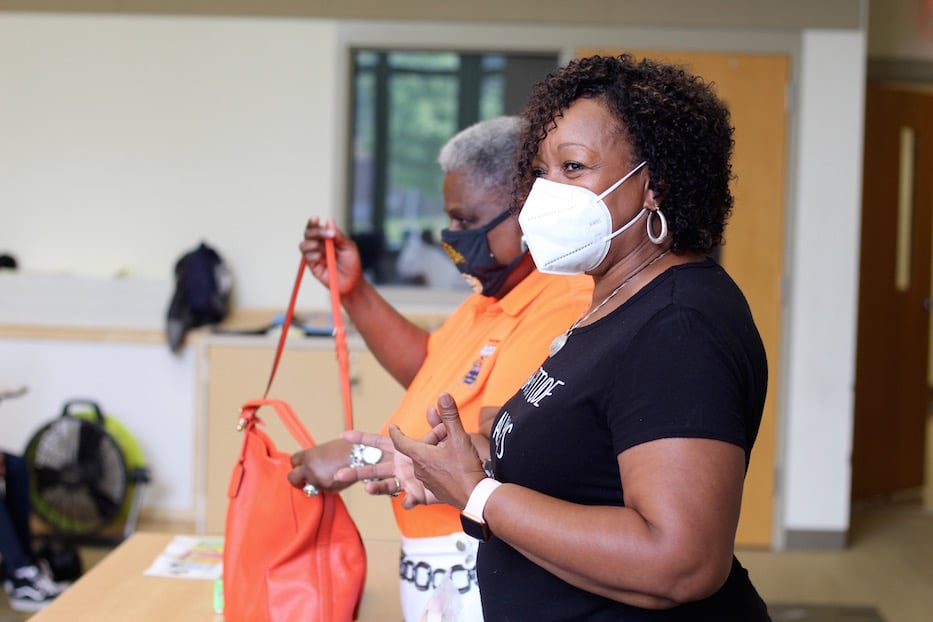

From left to right: Laila Williams, Brandy Cohens, and Zoe Smith. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Zoe Smith was halfway through designing a city when she realized she had forgotten the hospital. She picked up a piece of paper and moved it around, seeing if it would fit by the highway. Across from her, Laila Williams and Brandy Cohens debated whether it was okay to put a coffee shop next to a homeless shelter. Just when they thought they had figured it out, a palm-sized train station entered the mix.

That was a recent scene at Talented and Creative Youth Camp, run through the Monk Center for Academic Enrichment and Performing Arts at Davis Street School in upper Westville. This summer, the camp is bringing together law, chess, STEM (science,technology, engineering, math) education, and performing arts for in person learning after over a year of remote and hybrid school. It is helmed by Marcella Monk Flake, who founded the Monk Center in 2015.

“Starting the Monk Center enabled me to offer services like this,” said Monk Flake, who worked as a gifted and talented teacher for decades in the city’s public schools, and now holds programming at Augusta Lewis Troup and Edgewood Schools during the year. “We have been so blessed to have support.”

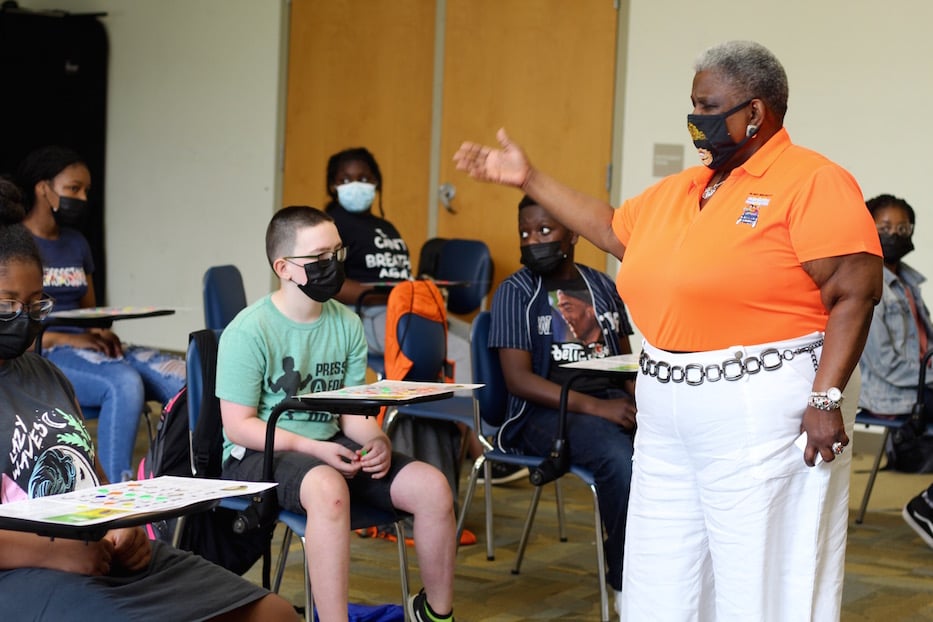

Marcella Monk Flake, who wore a shirt that read "#Gratitude is always on Trend." Dr. Dr. Beryl Irene Bailey is pictured in the background.

The program serves roughly 35 students over five weeks. It is part of the City of New Haven’s $6.1 million “Summer Reset,” which comes out of a $26.3 million tranche of American Rescue Plan funding that the city received earlier this year. On a recent Tuesday, students buzzed from a game of punctuation-themed bingo to an urban planning exercise to dance all before lunch.

Over the years, she has built partnerships that bring in chess coaches, members of the Connecticut Commission on Human Rights and Opportunities (CHRO), retired school teachers and administrators, and current members of the city’s Board of Education.

Last Tuesday, small groups of students spread out across the carpet of a classroom, chatting amongst the quiet hum of air filters. Sun-soaked games of chess unfolded in the adjoining room. At the front of the classroom, CHRO Deputy Director Cheryl Sharp held up a laminated sheet that caught in the light.

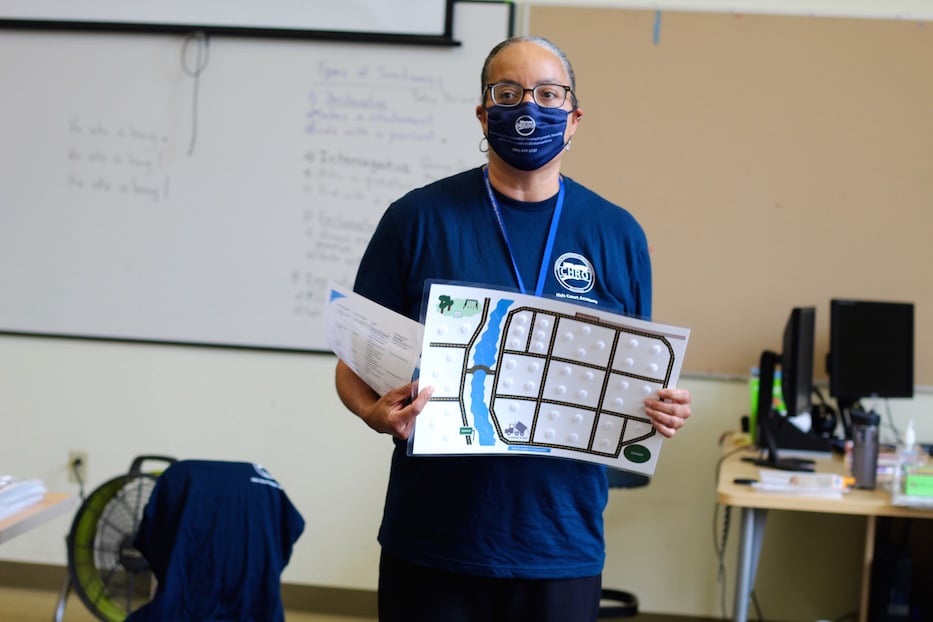

CHRO Deputy Director Cheryl Sharp.

On it, highways encircled a city covered in blank gridded squares, each with a tiny row of velcro dots inside. Sharp held up a baggie filled with small cutouts of houses, a hospital and church, fire and police stations and a trailer park. A rectangle with a peach-colored dust cloud and stairs to nowhere doubled as an abandoned lot. A green band ran through the cutout for a bank. She outlined the prompt: students had 25 minutes to build an equitable city.

“You can create an inclusive community,” she said. “Remember, you’re deciding what your community looks like!”

Except, she said, there was also a swamp to look out for. And a highway. And a garbage dump. And a babbling brook beside a playground that only some people could access. And a $500,000 limit on discretionary spending, with items that ranged from an amusement park to a YMCA. A spray of heart-shaped cutouts, each printed with a letter representing race, stood in for people.

Students started to unpack their pieces and puzzle over the maps. Sharp looked to Brown v. Board of Education, one of several U.S. Supreme Court cases they have been studying for the past weeks. She jogged students’ minds about details of the case.

Dr. Edward Joyner, whose grandson Eddie is in the program, joined to talk about getting a doctorate in education. He shared with students that because of finances, he had to stop and start his undergraduate education several times before going on to graduate school.

“Is separate but equal good?” she asked. Hands shot up around the room.

“No!” Joey Sclafani cried from the middle of the classroom.

“No!” Sharp agreed, weaving between clusters of students. “It is inherently unequal! You are going to have to decide who is going to live near the swamp? Who is going to live near the highway? Who is going to live near the garbage dump? I want you to dig deep and think about who you are.”

At the far edge of the room, Smith, Williams and Cohens settled in a pool of sunlight and turned toward their maps. Williams held the hospital between her fingers, studying the road that wrapped around the city like a thick geometric snake. She moved it around to different locations, nixing the idea of putting it downtown almost as soon as she had tested it out.

“It’s gotta be on the highway, right? So it’s easy for people to get to?” she said. She smoothed it to a velcro circle and started looking at where to place the empty lot.

.jpg?width=933&name=Creative%20-%201%20(2).jpg)

Across from her, Smith asked if it seemed smart to put the courthouse next to the police station, and whether they could be on the outer ring of town. She wondered aloud if one coffee shop was enough for a small city, or if residents needed a second one. A small cutout of a rainbow flag, designating a pride center, sat untouched in the middle of her map.

Sharp walked around the room, watching as large houses landed in the center of town, with hearts printed “B” and “W” to show that it was an integrated neighborhood. She studied medium houses that popped up on the periphery. She looked over a group that had chosen to place the trailer park beside the swamp. Hearts for Indigenous and Asian people still sat to the side, waiting to be placed.

Every so often, she dropped a new piece into the mix. A homeless shelter. A towering red brick apartment complex. A train station. The last few—deemed “extras” to reflect a trend that Sharp sees in her work around the state—included youth programs and access to disability services.

Smith, Williams, and Cohens placed a YMCA as their final piece, a development that left them $300,000 in discretionary spending to work with. One group over, twins Joey and Miles Sclafani and their friend Ethan Works selected an amusement park. It would cost them the entire $500,000 budget.

Sharp called time.

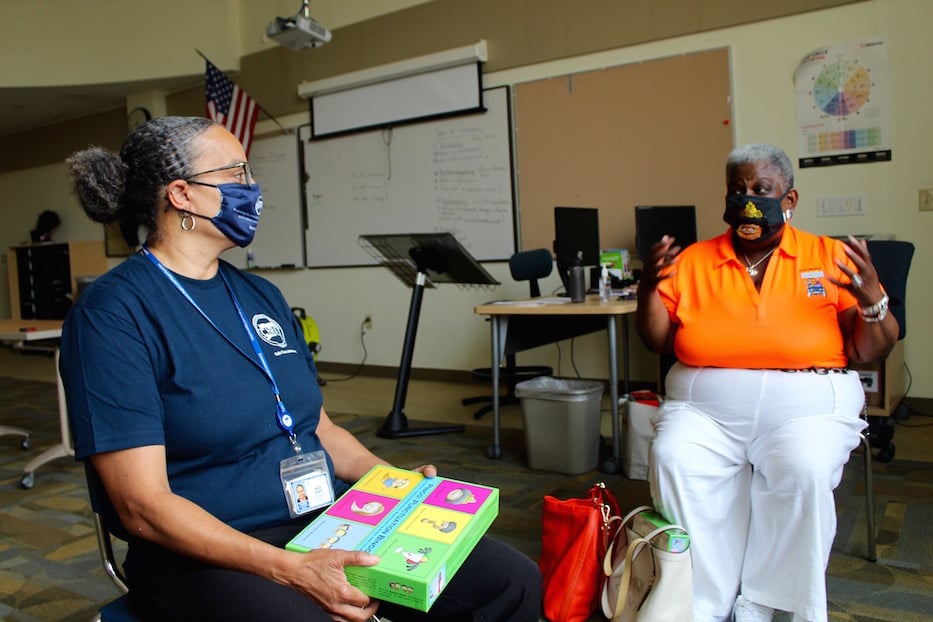

CHRO Deputy Director Cheryl Sharp with Dr. Beryl Bailey before class started.

She studied different designs that bloomed across the room. One group had placed an apartment building beside the garbage dump, with the assumption that residents would create a lot of trash. She chewed on the debate over whether to build a YMCA or an amusement park.

“Raise your hand if you think it’s better to have a YMCA or an amusement park,” she said. Almost no hands went up for the YMCA. Williams bravely lifted her arm into the air.

“Because people should be able to go to camp,” she ventured. Sharp nodded. She told the class that amusement parks are fun—but they also assume that the people who use them have money to spend. What about houses, she asked.

“We put Black and white people together in medium homes because we think that everyone is equal,” Williams said.

“Did you hear that?” Sharp said. “We have some of the most segregated cities in America right here in Connecticut. They made a choice to be inclusive.”

In between civil rights trivia questions and factoids around New Haven figures like Constance Baker Motley, she later told students that the work is personal to her. Born and raised in Hartford, Sharp was bussed out of the city to a suburban school district as a kid, and saw the state’s segregated school system in real time. After graduating from the University of Connecticut’s School of Law, she started as a law clerk with the CHRO in the 1990s.

She recalled entering a courtroom with two fellow attorneys, ready to discuss a case on which she had written the brief and taken the lead. The other two attorneys were both white. Sharp is Black. The judge turned to her and asked if she was there to carry the bags.

“It’s my case!” she said as students listened, hanging onto each word. “And it’s my brief! And he said ‘Are you here to carry the bags?’”

She now runs CT Kids Court Academy, a weekly program that teaches young people about equal rights through legal precedent. When she told students that she had struck a deal with Monk Flake—any camper could automatically enter the Court Academy if they applied—small hands pressed to flushed, masked cheeks in delight.

“Sometimes I think the expectations for kids of color are really low,” Sharp said before she left for a day of back-to-back meetings. “They shouldn’t feel limited to a specific profession. When you realize that you can do anything, there’s a bell that goes off.”

“Pingo!”

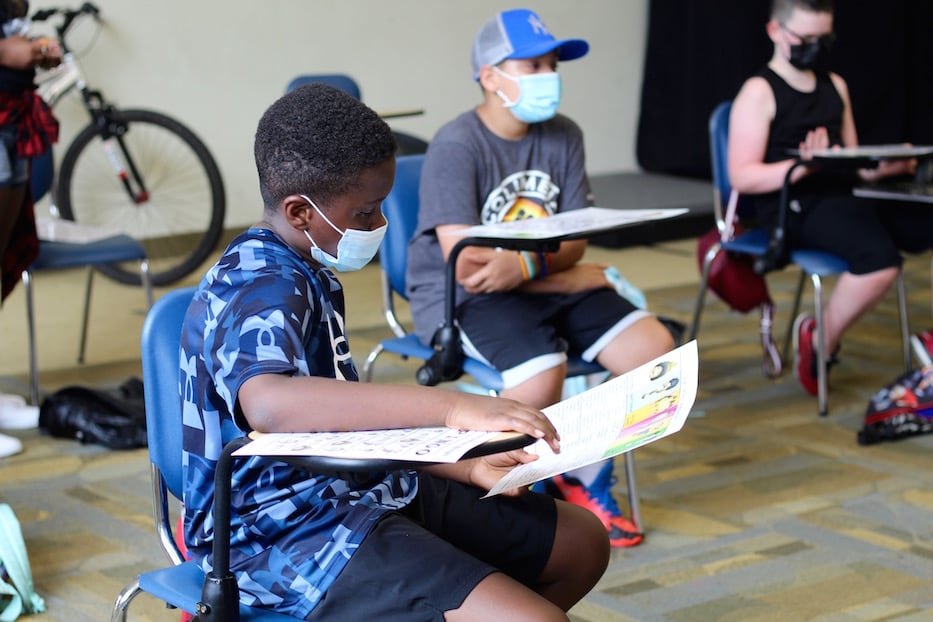

Dr. Beryl Irene Bailey with Miles Sclafani.

Tuesday morning also included a visit from Dr. Beryl Irene Bailey, director of literacy for the Bloomfield Public Schools and the creator of the Punctuation Posse Patrol and From Pages to Pedagogy LLC. The project, which includes a punctuation-themed bingo game called Pingo, gamifies literacy learning.

For Bailey, it’s part of a mission to spread the gospel of language and of grammar. Growing up in New Haven, she and Monk Flake both competed in oratorical contests and became students in Yale’s now-defunct Upward Bound program, often cheering each other on if one surged ahead. The two have been friends since meeting at Thomas Chapel Church of Christ in the city’s Hill neighborhood five decades ago. Monk Flake introduced her to students as “not just my friend, she’s also my sister.”

“We were given the message that you could be anything that you want to be,” Bailey said before class, her mask emblazoned with a crowned, curly-haired character named Patsy Period. “I noticed that in literature, language is a code. It carries meaning. In giving students standards around punctuation, it helps them. It helps me too!”

Edward Joyner III, who goes by Eddie.

As she passed out pingo boards, characters greeted students with wide eyes and big smiles. There was Patsy Period, with whom students were already acquainted, as well as Eric Exclamation Point, pink-lipped Courtney Comma, the Quotation Quartet in red and white pinstripes. For Bailey, good punctuation is like a system of synchronized traffic signals. She sees beauty in its precision.

She lifted an index card as students watched, all eyes on her. In preparation for her visit, they had learned a rap about punctuation that Bailey wrote and produced with her son. They braced for the first question, clear pingo chips in hand.

“Could the crippled spaceship make it to the moon?” she asked. At the far left of the classroom, Edward Joyner III raised his hand.

“Quincy Question Mark!” he answered. Bailey lifted another card.

Student Kadasia Foreman with Bailey.

“His sister asked, ‘Calvin, can you fly?’” she asked.

A few hands went up. Students teased out Courtney Comma and the Quotation Quartet. Quincy Question mark returned at the end of the sentence. Bailey walked around the front of the classroom, then headed toward the quiet back row. She called on students who hadn’t yet answered, leaning in for murmurs from the back of the classroom.

“You are a very perspicacious group!” she said.

“Trust Yourself”

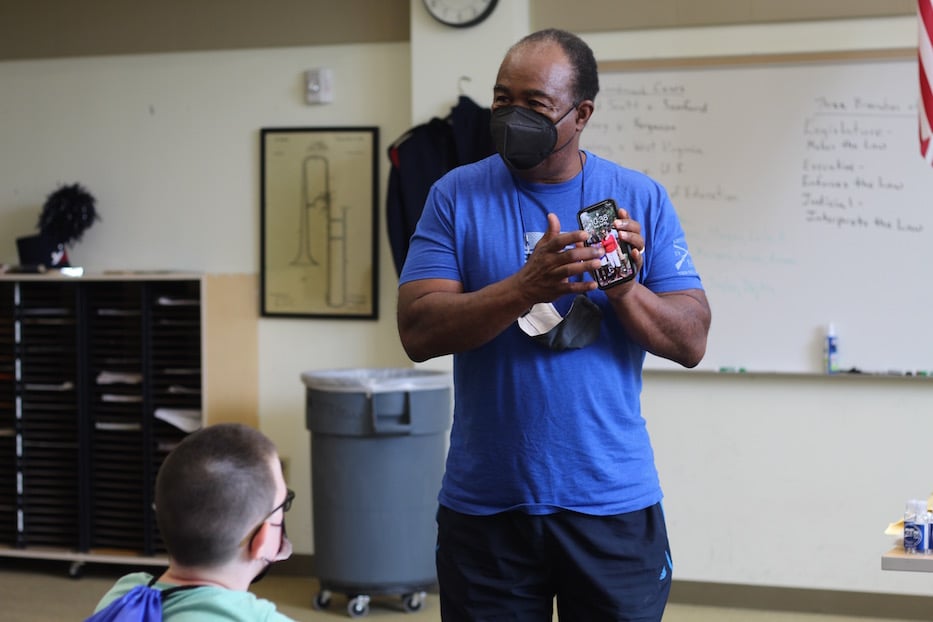

Bruce Trammell: "I want them to have that kind of fun.”

One room over from the unfolding game of pingo, fatherhood coach and chess pro Bruce Trammell was tidying up after a morning session of chess. The words “Trust Yourself” were written across the board. He said that his goal in teaching the game “basically from zero” is to build decision making skills that students can take with them wherever they go.

His own father started teaching him to play when he was nine, in what became tournaments across the Northeast Corridor. He hasn’t stopped playing since. He wants students to have the same interest in and respect for the game that he does. He currently teaches about 22 students.

“It’s been fun for me,” he said, recalling how his father would start tournaments in Burger King and McDonalds. “And I want them to have that kind of fun.”

.jpg?width=933&name=Creative%20-%201%20(1).jpg)

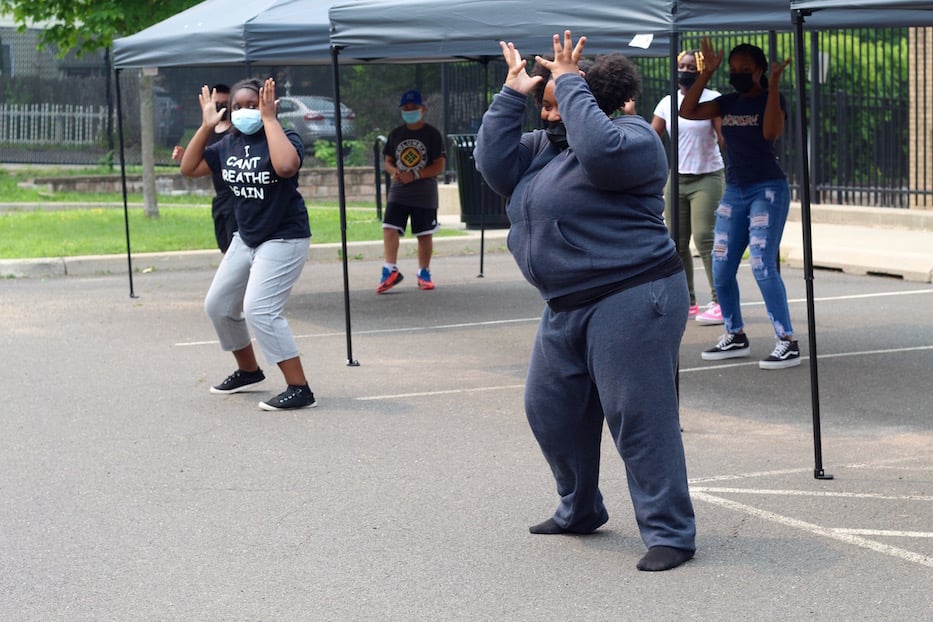

Top: Laila Williams. Bottom: Flake (in foreground) and Naima Jahad.

Outside, campers spread out under tents, cool in the shade. Alisha Flake, who is Monk Flake’s 21-year-old daughter, cued up Beyoncé’s “Already.” The words pulsed and seethed through a speaker. Students, heads still buzzing with the urban planning exercise, lowered their heads and extended their hands. Then the beat dropped.

Naima Jahad, a rising seventh grader at Mauro Sheridan, snapped from stillness to movement as if someone had flipped a switch. The group moved in a wave, arms lifting in time with the beat. Monk Flake watched from the side, eyes fixed on each dancer. Jahad later said that she likes the camp’s ability to weave singing and dancing with Black history.

“I just like to move,” she said.

Follow the Monk Center for Academic Enrichment and the Performing Arts here.