Co-Op High School | Education & Youth | Long Wharf Theatre | Arts & Culture | Theater | COVID-19

Screenshot from YouTube.

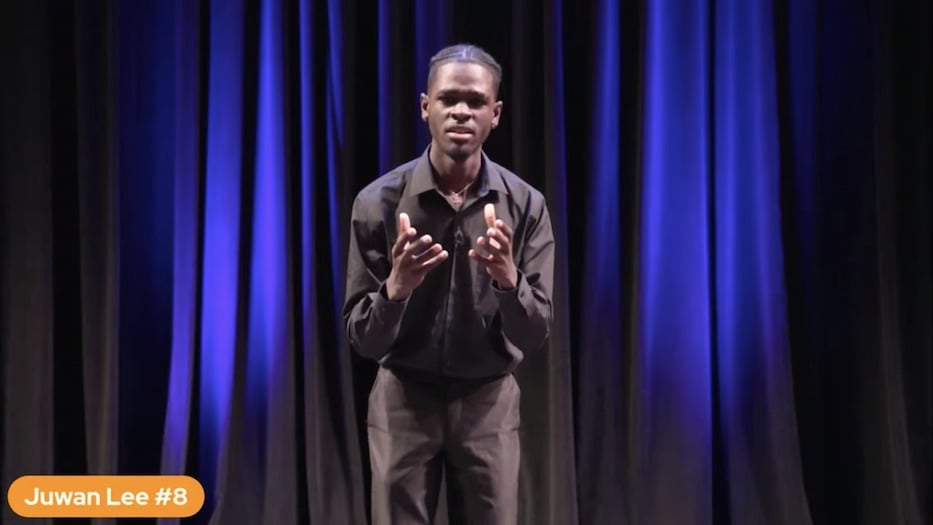

Juwan Lee stood with his hands out in front of him, catching in the blue light. He looked into the camera, then back down at his long, upturned fingers. As he spoke, he conjured a home in Pittsburgh, where an old, beloved piano could bring new wealth into the family. He conjured a home in New Haven, where a young man needed the funds to attend his dream college. By the second paragraph, he was both Juwan from New Haven and Boy Willie from The Piano Lesson.

“I ain’t got no advantages to offer nobody,’” he said, eyes locked on the camera. “Many is the time I looked at my daddy and seen him staring off at his hands. I got a little older I know what he was thinking. He sitting there saying, ‘I got these big old hands but what I’m gonna do with them?’”

Monday night, Lee joined 15 students from across the country in the 2021 August Wilson Monologue Competition (AWMC) finals, held online due to the Covid-19 pandemic. For four years, he has been part of the competition as a student at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School and Long Wharf Theatre, which is the competition’s regional partner. Monday marked the first time that he performed on the finals stage. This year, his performance crystallized the grief and exhaustion of the last year, which has thrown a city in contrasts into sharp relief.

While he did not win, he said the competition helped reignite a passion for theater that he very nearly lost this year. In the past 14 months, he has faced the grief of losing family members to Covid-19 while also holding down remote school and a part-time job.

“It was an honor to be on that stage,” he said Monday night after performing. “This year has been really, a very pulling year. It’s been really stressful. I’ve lost so many family members to the Covid virus. I’ve lost myself to this virus. I was going through a great deal of depression. Being able to perform again … I felt the warmth of that stage.”

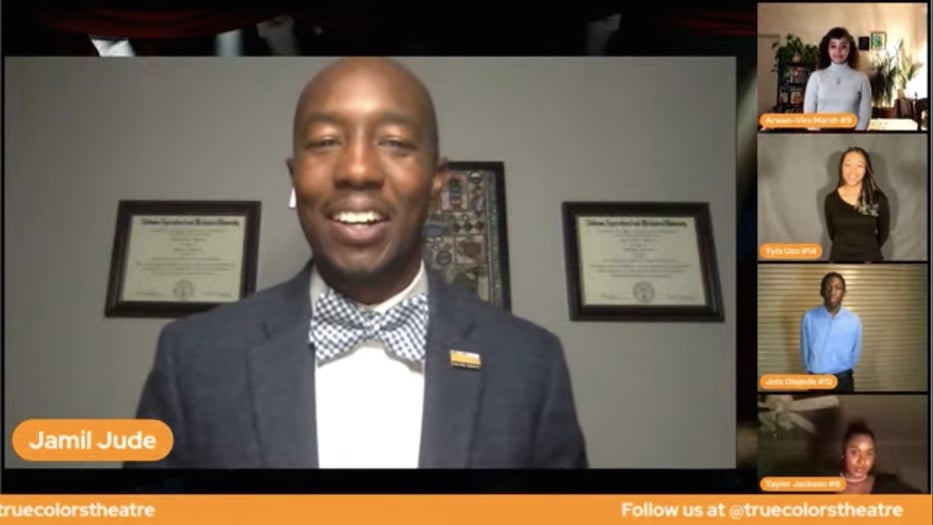

For Lee, the annual performance has become something of a holy rite. Fourteen years ago—when the actor was still in nursery school—Kenny Leon and Todd Kreidler founded the competition at the True Colors Theatre Company in Atlanta. In its current format, students choose and perform monologues from Wilson’s heralded American Century Cycle, a series of ten plays chronicling ten decades of working-class, Black American life in 20th century Pittsburgh and Chicago. Monday, True Colors Artistic Director Jamil Jude announced that it will be going on hiatus next year.

The city’s chapter is a collaboration among Long Wharf, Yale Repertory Theatre, and multiple high schools across the region. This year, teaching artists included Jacqueline Brown and Julius Stone. Lee, who performed the same monologue last year, was forwarded to regionals and then finals when last year’s competition became a casualty of the Covid-19 pandemic. Students Tiana Bailey and Isabella Seery, who both study at the Greater Hartford Academy of Arts, also progressed to regionals but did not perform in finals.

Monday, students dipped their hands into Wilson’s words and mined them for their history, lyricism and stinging relevance. As actors waited in the digital wings, a parade of professional actors, directors, coaches and mentors wished them luck. Joaquina Kalukango, who won the inaugural competition in 2007 and is now on Broadway, encouraged actors to channel all of the emotional exhaustion of this year into their three or four minutes on stage.

“I know this has been an incredibly hard and trying year and a half for so many of you,” she said. “So for you to be here, in this moment, sharing the work that you’re gonna share, is going to be incredibly profound, and moving, and also healing. That’s our power as storytellers, right? And so, I want you all to understand as artists, you were made for that moment.”

For over an hour, they did. Through screens set up across the country, students harnessed the toll of the pandemic and pushed through it, with performances so intimate they felt immediate and three dimensional. As the first performer of the evening, DRW College Prep senior Dalencia Brown drew audience members into Wilson’s world as King Hedley II, the room around her suddenly an entire world.

She transported the audience back to 1980s Pittsburgh, where the formerly incarcerated Hedley II is trying to put his life together, one refrigerator sale at a time. In the monologue, King Hedley II is on his way to buy potatoes when he gets into a fight. While Hedley II initially tries not to fight, his anger rises when a character cuts him across the cheek.

“I didn’t know what happened,” she said, rage and fear duking it out at the edges of her voice. “It was like somebody turned on a light and it seem like everything stood still and I could see him smiling.”

She pulled something dark and pained straight from her ribcage. King Hedley jumped into a scuffle, and she made him move with pith and empathy. Her body rippled and shuddered with the words. She hurled racial epithets with a precision that could nearly slice skin. By the time she had finished, she had given a stunning rebuke of the carceral state without ever saying the word “abolition.”

A parade of Veras, Hedleys and King Hedley IIs, Molly Cunninghams, Bernices and Memphises followed, each pulling their characters through the thick muck of a year that has seen deep racial unrest, uprising, surging white violence and nationalism, and twin pandemics of Covid-19 and white supremacy.

Arwen-Vira Marsh played Wilson’s Vera for the quiet, simmering pain baked into Seven Guitars. Taloria Merricks let the same character’s red-hot rage take over, her voice hard. Pittsburgh-based student Shakyna Golphin stopped space and time when her Hedley announced that “The black man is not a dog! He is the Lion of Judah!” and audience members could see, in a flash, a summer of protests against police brutality. As Bernice, Grand Prairie High School Junior Jayla Gossett made her uncle’s piano so real one could see its polished keys catching the sunlight as she read.

When Lee was up, he steadied himself with a single, deep breath. Behind him, the curtains on Long Wharf’s Stage glowed in anticipation. He looked right into the camera, drew in his cheeks, and lifted his hands. It wasn’t a gesture of supplication, but a sign that he was ready to verbally spar. His voice was a rising tide.

“What I want to bring a child into this world for?,” he began. The words crackled with electricity. “Why I wanna bring somebody else into all this for?”

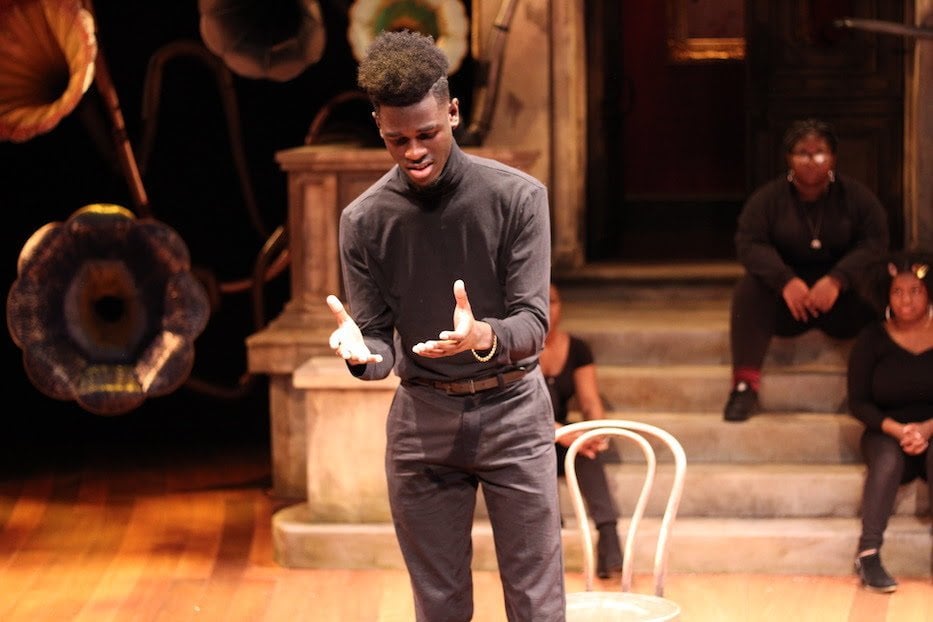

Lee performing the same monologue at Long Wharf Theatre in February 2020. Lucy Gellman Pre-Pandemic File Photo.

In the play, set in 1930s Pittsburgh, Boy Willie is trying to convince his sister Bernice to sell their uncle’s piano. In the “piece of wood,” as Wilson calls it, Willie sees untapped economic potential, and a step to a better life. Bernice, meanwhile, sees a family heirloom full of sentiment and memory. Between them, Wilson unpacks not just a family dispute, but a pattern of economic disenfranchisement and land theft that is centuries old. It feels deeply, unsettlingly current in a year when high Covid-19 infections and deaths can be mapped onto chronically underfunded neighborhoods and redlining maps from the twentieth century.

As Lee unspooled the monologue, he told the story of not just Boy Willie, but of how the last 14 months have transformed his own life. Lee, who is the youngest of four children, lives in the city’s Newhallville neighborhood with his aunt. When he isn’t in school, he’s a church musician and freelance actor. His mom is a flight attendant, which means that “I’ve really been more independent than anything for most of my life,” he said. At Co-Op, he’s been a part of the August Wilson Monologue Competition since his freshman year.

In 2018, Lee chose a monologue from King Hedley II, making the words his own as he proclaimed “My fifth grade teacher told me I was gonna make a good janitor” and charged forward. When he didn’t place, he dug deeper into both Wilson’s repertoire and his own dramatic work. He rehearsed for weeks, then months. From Fences’ Troy Maxon his sophomore year, he worked his way to Boy Willie in 2020.

By then his faith in theater, which he hoped to study at Morehouse College in Atlanta, was strong. Last year, the young actor scored a spot in regionals in late February. He was in the early stages of a table read for Allan Appel’s My Liberia, a play about free Black architect and engineer William Lanson, at Bregamos Community Theater. He had just finished a short run of Matthew Rising, by local playwright Sharece Sellem.

Merricks, who ultimately took first place for her portrayal of Vera from Wilson's Seven Guitars.

Then the pandemic hit New Haven. It shut down the regional competition. Table reads at Bregamos screeched to a halt. Schools announced that they were going remote. Lee, who had played Boy Willie with a quiet, understated sort of fury in 2020, felt suddenly unmoored. As Covid-19 ravaged New Haven, he lost multiple members of his family to the virus.

“It was like, okay, stuff is being snatched away—what do I do?” he said. “Do I just sit and rehearse my monologues for the year, or do I think about life? I lacked the will to perform during the pandemic. I was like, acting is stressful. You’re in your house. You’re by yourself all the time, and you’re trying to figure out what you’re going to do with life. It was very, very very depressing for me to be in my house. It has been very pulling on the heart.”

He trudged through because he had to, he said. He applied to colleges. Like many students this year, he learned to juggle school and a part-time job, during which time he’s maintained a 4.1 grade point average. He thought seriously about quitting theater. And then the competition popped back onto his radar. He learned that he would have the chance to repeat the Boy Willie monologue on Long Wharf’s stage. This time, instead of a live audience, he would have a video camera.

“We were so happy that Juwan was able to jump back in there,” said Azaria Samuels, audience development and corporate partnerships coordinator at the theater. “He wanted to make sure that he did this and represented for males in New Haven, but he also wanted his fellow sisters and brothers in New Haven to know that they can do this.”

Lee said that when he returned to the script, he related to Boy Willie’s pursuit of economic opportunity. Lee was admitted to Morehouse earlier this spring—but he is unable to attend due to funding. Instead, he’ll be at the University of Connecticut, which offered him a full scholarship. Morehouse, which is a Historically Black College, had been his dream school since he was eight years old. His older brother is an alum. He recalled feeling devastated.

“At an HBCU, I’d be able to connect with many Black individuals,” he said in a phone call. “I love the brotherhood aspect of it—I love to be able to talk to my brothers and negotiate any life problems. I don’t feel that I can do that at any PWI [primarily white institution].”

Performing the monologue helped him sort through those feelings in real time. Lee said he often thinks about the fact that Wilson based his characters on people he saw and overheard in coffee shops, spinning them into a portrait of working-class Black America that is still relevant today. When he reads Wilson, he sees characters who could be his siblings or his relatives. He loves slipping into those roles and trying them on for size, he said. Returning to Boy Willie in the midst of a pandemic, when funding was the one thing between him and his dream school, felt right on time.

“There are so many things that stand in our way as young people, and one of them is money,” he said. “That’s how I was able to understand Boy Willie. Money can really stand in the way, for greater and for worse.”

Co-Op drama teacher Robert Esposito—or as students prefer, simply “Espo”—has been working with Lee on the competition since his freshman year. He recalled watching Lee walk into the practice room in 2018 and realizing that there was a well of talent waiting to burst free.

“He just had this wonderful sense about him that went beyond what anyone his age should be able to access,” Esposito said in a phone call Wednesday night. “Usually, when you come from middle school, you’re just not emotionally ready. But there's a handful and Juwan was one of them. He was able to really do really good advanced work, even at that freshman year. It was almost like I was coaching my seniors.”

Since, the two have worked together on the competition and in the classroom. Esposito was also part of the table read for My Liberia in February, which he now worries could have been a spreader event. He said that he’s hopeful for Lee’s future at the University of Connecticut, and glad he was able to close out his senior year on stage. While he will be sad to see him go, he is immensely proud of the work he has done during his time at the school.

“He’s not the loud boisterous boy,” he said. “He’s the quiet kid who sits in the back of the room, gets lost in his thoughts. When I see a kid like that, he’s thinking thoughts that 30 year olds are thinking. He’s thinking thoughts and having emotions that are really mature, because he’s an artist.”