Education & Youth | Long Wharf Theatre | Arts & Culture | Theater | Yale Rep Theatre

| Koda Blue performs as Ma Rainey from Ma Rainey's Black Bottom (1982). Chloé Lomax-Blackwell, who took second place last year, performed the same monologue with a simmering, cutting anger and knowledge beyond her years. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

Koda Blue was fully herself and also fully Ma Rainey, her body a lightning bolt ready to strike. The year was somewhere between 1920 and 2020, in a recording studio somewhere between Chicago and New Haven's Dixwell Avenue. She felt out the air—combustible and tight—and exploded into sound. In the span of two arms and two legs, Ma Rainey was reborn, balletic and enraged with the weight of every single word.

It paid off. She’s now headed to New York to perform that monologue on a national stage in May.

That kind of risk taking defined New Haven’s fourth year participating in the August Wilson Monologue Competition, the regional finals of which were held Monday night at Long Wharf Theatre. Of over 100 students who trained and auditioned for the regional competition, 15 finalists competed for two slots to go to New York City in May. The finals will be held May 4 at the August Wilson Theatre in Manhattan.

The competition was founded in 2007 by Kenny Leon and Todd Kreidler at the True Colors Theatre Company in Atlanta. Students choose monologues from Wilson’s heralded American Century Cycle (also referred to as the Pittsburgh Cycle), a series of ten plays chronicling ten decades of working-class, African-American life in 20th century Pittsburgh and Chicago.

The city’s chapter of the August Wilson Monologue Competition is a collaboration among Long Wharf Theatre, the Yale Repertory Theatre, and multiple high schools in New Haven, Hartford, Fairfield, and Trumbull. This year, judges included New Haven playwright Sharece Sellem, NXTHVN Executive Director Nico Wheadon, and Yale School of Drama MFA students Dani Barlow, Laurie Ortega-Murphy, and Chris Audley Puglisi.

The competition has specific resonance in New Haven, where six of the cycle’s works premiered at the Yale Rep. The city is currently among 14 cities in the competition, including Atlanta, Chicago, Greensboro, Los Angeles, New York, Pittsburgh, and Seattle among others. In New Haven, it is run by Long Wharf Education Programs Coordinator Jacque Brown and teaching artists Cecilia Kurachi Ubé and Justin Pesce.

| “The sheer talent I had the pleasure to witness in our workshops warmed my heart." |

“The sheer talent I had the pleasure to witness in our workshops warmed my heart,” said Jacque Brown, education programs coordinator at the theater.

Monday, Yale School of Drama Dean James Bundy recalled welcoming Wilson’s Radio Golf to New Haven in 2005, when it premiered at the Yale Rep as the final play in the Pittsburgh Cycle (at the time, it was directed by Timothy Douglas). Fifteen years later—and with Wilson’s reading of structural racism still pulsing and raw—Bundy suggested that Wilson would have delighted in knowing that so much of his language was living on in young people.

“I know nothing would give him greater pleasure than to see these young people up on this stage,” he said.

Monday, all 15 finalists brought fierce, explosive, quiet, and deeply personal interpretations of Wilson to the competition. Framed by Britton Mauk’s set for I Am My Own Wife, students walked onto the stage as themselves, then seemed to transform as they took their moment in the spotlight.

Some, like Blue, plunged their hands into words written in the 1980s and pulled out something new and just as hard-hitting, more akin to a piece one might hear at a city-wide poetry slam than on a dramatically lit stage. Drawing on Wilson’s work—the play is modeled on the real-life jazz colossus of the same name—Blue stepped into a Ma Rainey that was also her own.

As she introduced herself and launched into the monologue, Blue seemed aware of how much space was around her body. The actors behind her, each waiting for their turn to perform, faded into the background. Her back hunched and unhunched. Her arms sliced through the air. It crackled in return.

In the play’s world, Ma Rainey is ready to trash talk her manager Irvin, a white man whose refusal to cover her five cent coca-cola speaks volumes about the economic exploitation of Black labor. She is in a recording studio, surrounded by some of her band members. But Monday, the play’s world was also Long Wharf, almost a century later. And Blue was having none of it.

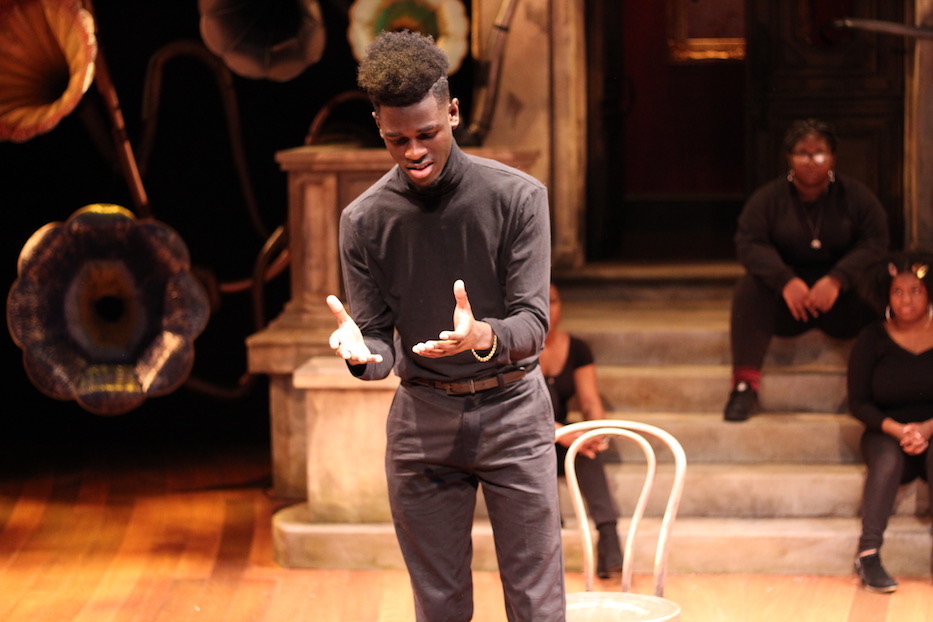

| Emmanuel Gonzalez, who performed Levee from Ma Rainey's Black Bottom. |

As she spoke, she put her whole body into becoming not the Ma Rainey that Wilson wrote in the 1980s, but the Ma Rainey that could exist within her own lived experience. She summoned the number of Black and Brown New Haven artists in the city who are still exploited for their labor, and asked to work for free.

A cool, steely edge of something worked its way around the corners of her voice. Her body moved in time with the words.

“They don’t care nothing about me,” she said. “All they want is my voice. Well, I done learned that, and they gonna treat me like I want to be treated no matter how much it hurt them. They back there now calling me all kinds of names … calling me everything but a child of God. But they can’t do nothing else. They ain’t got what they wanted yet.”

As she performed, she spoke directly to the poetry, cadence, and aching permanence of Wilson’s work. In the play, Ma Rainey never has to name structural racism and the legacy of slavery, because she speaks them both into being. On stage, Blue seized on the humor, self-possession and self-sufficiency that so define the character, showing how an old legend can speak new truth to power.

She opened a door through which other actors strode, tiptoed, and all but galloped over the next 90 minutes. Ivan Lazaro, a student at Educational Center for the Arts who trained with Pesce, tempered his anger as Levee from Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, so that a simmer grew into a full-lunged, rounded rage. Serenity Lawrence played Black Mary for her quiet moments, her words heart-rending even at a near-whisper.

Juwan Lee, a junior at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School who took home second place, brought a kind of quiet fire to Boy Willie from Wilson’s 1987 The Piano Lesson. From the moment Lee’s body was on stage, he let the words roll off of him with a simmering, muted sort of anger.

| Juwan Lee. |

Then suddenly, something boiled over. Lee’s shoulders and extended palms held Depression-era policies, but also the legacy of redlining, mid-century urban renewal, and deliberate economic deprivation that plagued Black and Brown families in the years that followed. The character’s case for owning land may have been set in depression-era Pittsburgh, but it felt like it was pulled from Ta-Nehisi Coates' 2014 essay The Case for Reparations.

“If he had something under his feet that belonged to him he could stand up taller,” he said, stomping his right foot with a sudden, sharp crack that reverberated through the theater. “That’s what I’m talking about. Hell, the land is there for everybody. All you got to do is figure out how to get you a piece.”

In a show stopping performance as King Hedley II, Wilbur Cross High School student Brandon Oliveras mined Wilson’s language for sharp, bitter humor. From a chair, he sprang up arms and core first, criss-crossing the front of the stage. He took Hedley’s story—about a teacher who told him he would be a good janitor, because he was so good at cleaning the blackboard—and turned it into entirely his own.

“I come home and told mama Louise I wanted to be a janitor,” he recited, turning the theater into an intimate conversation. She told me I could be anything I wanted. I say, ‘Okay, I’ll be a janitor.’”

He paused, and let the line hang in the air. A few attendees shifted in their seats. Others laughed, the low, gurgling kind of that comes out of knowing something isn’t right. As he continued, it was hard not to think of a Hamden teacher who last month had a young Black student play an unnamed enslaved African in a class play. Oliveras let the line fall and pressed on, kinetic.

| Brandon Oliveras as King Hedley II. |

Others probed the unchanging weight of Wilson’s text. For a second year in a row, students stunned with monologues from Gem Of The Ocean (just as there were multiple Veras in 2018, there were five Black Marys this year) and King Hedley II, each of them stinging because they could have been written this year.

As she took the stage, alternate Soleil Wolcott stepped into the role of Tonya, balancing past and present with every sentence. In the play, the character has told King Hedley II that she is pregnant with his child, and that she plans to have an abortion. While King Hedley II was written in 2001 and is set in the 1980s, her words rang out like a long, hard slap.

She conjured a family down the road, a home materializing around her. Hedley stood somewhere close to the front row, where her gaze stayed fixed.

“She don’t know Junior don’t need no more clothes,” she said. “She look in the closet. Junior ain’t got no suit. She got to go buy him a suit. He can’t try it on. She got to guess the size. Somebody come up and tell her, ‘Miss So-and-So, your boy got shot.’ She know before they say it. Her knees start to get weak. She shaking her head. She don’t want to hear it. Somebody call the police. They come and pick him up off the sidewalk.”

In them, it was hard not to think about the epidemic of violence, some state-sanctioned, against Black and Brown bodies that is still raging across the country. It was hard not to think of Demethra Telford’s grief that her son Tyrick Keyes, who was killed in Newhallville in 2017, was never coming home. And concurrently, of the fact that Black women are often denied the prenatal care they need, and still three to four times more likely than their white counterparts to die in or following childbirth.

By the end of the night, 15 students had arrived on the stage as themselves, bright eyed and coordinated in their black-on-black outfits, and left as truth tellers.

In a theater that LWT Artistic Director Jacob Padrón christened “of, by, and for the community" at the beginning of the night, Wilson’s spirit seemed to vibrate through the seats, wedge its way in between eager family members (“hey that’s my cousin!” one excited voice yelled out during a smattering of applause), stick around for an interlude from the artist Thabisa and for the results.

Peers embraced each other as the winners were announced. Blue covered her mouth with one hand and started to cry after accepting first place. Cake and cider waited for a party in the lobby.

But those young voices, strong enough to raise the rafters, also left a question hanging in the air.

Wilson’s work is timeless. Does it have to be?

To watch the beginning and the entirety of Monday night's competition, click on the videos below.