Dance | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | New Haven Public Schools | COVID-19

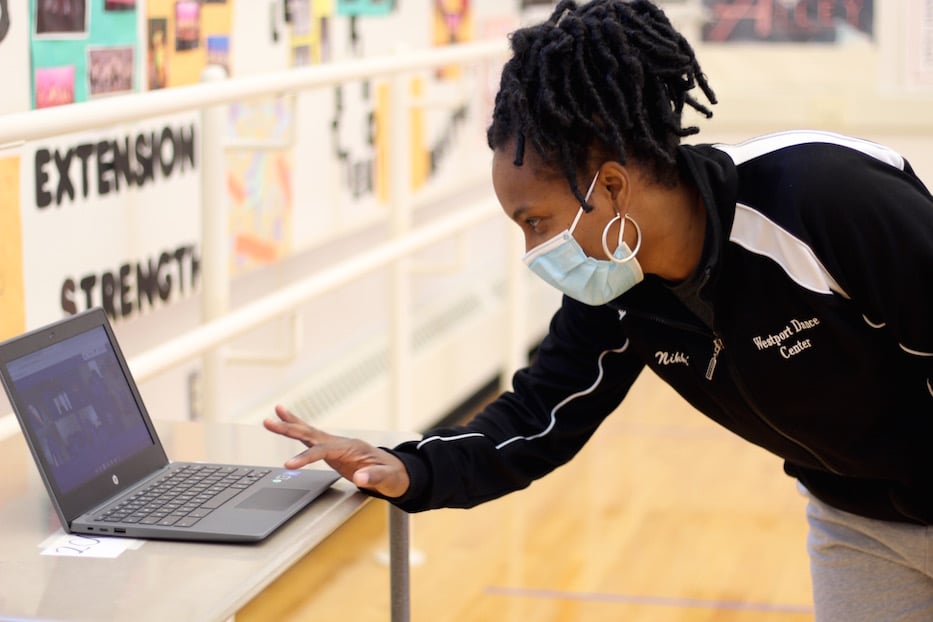

Bauer, who is also a co-founder of Elm City Dance Collective, in a recent Zoom call. Screenshot via Zoom.

Lindsey Bauer reached out to her right, a screen balanced in front of her. She reached out to her left, into feet of open space. On the other side of the screen, students looked back. She urged them to imagine that there were people—mothers, aunts, friends—holding out their hands in return. It became a meditation, bodies moving slowly into what looked like a hug.

Bauer is a dance instructor at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School in New Haven, where classes have been remote since March 13 of 2020. As the Covid-19 pandemic goes on a full year, she is one of dozens of dance instructors across the state who are using technology to redefine their pedagogy and connect with their students across the distance. She is also one of several doing it with young kids at home.

“It’s been really challenging,” she said in a recent interview over Zoom, holding her 2-year-old son Etienne as he fiddled with her headphones. “At the same time, it’s nice to be able to come face to face, to come together and try to create a virtual school, which we’ve done. And it’s been really nice to see the ways that we have been made to be more creative, because we’re online. The restrictions that we have, and how that can spur new ideas about the form.”

Last year, Bauer struggled to engage with her students during the spring semester, as a projected few weeks away from school turned into three months, and then a second academic year. Initially, she said, “nobody really knew what was going on.” In classes, cameras stayed off and left her feeling like she was speaking—or moving—to an empty room. The only students she saw in person were her graduating seniors, alongside whom she did improvisational dance during a socially distanced graduation ceremony at Lighthouse Point Park.

When the city’s Board of Education announced that classes would remain remote last fall, she worked to expand what dance could look like over a screen. Even before Covid-19, Bauer made a habit of checking in with her students before class. This year, she said, that practice has taken on an added weight. It often dictates the flow of the class, from warmups rooted in yoga and meditation to floor work that is done in living rooms, bedrooms, and kitchens.

“A lot of times, I’ll ask my dancers, like, ‘What do your bodies need?’ Or, ‘What does your soul need today?’” she said. “I’m in a discipline where our bodies speak. And we spend most of the class period speaking with our bodies, and not with our voices. Not with our hands, typing.”

In the before times: Bauer teaching Girls In Motion, an after-school collaboration between Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School and Connecticut Capoeira and Dance, in October 2019. Lucy Gellman Pre-Pandemic File Photo.

She recalled a recent class, during which she could feel the energy shifting and crackling even behind the screen. Students were quieter than usual. When she asked what was going on, students hesitated, then explained that someone in the school had used a racial slur on social media. It had rippled through the school community. Because of the pandemic, there was no way to come together and address it in physical space.

In an instant, Bauer knew that her whole lesson plan had been upended. She pulled out paper and began to take notes about what happened and how it was sitting in students’ bodies. She made plans to talk to school administrators, which she did later in the day. Then she focused squarely on her students. She had them reach out their arms, as if they were reaching to touch the hands of their loved ones. Right hands extended. Then left. She let students take time to connect with their bodies.

During the Zoom call, she recreated the movement with her right arm, suddenly extended to its full wingspan.

“I was hoping that would feel like a hug,” she said. “Or feel like shared kindness and shared experience. And that we create a community together, even though we’re through a screen. And reminding them of this goodness, because there’s so much to sift through.”

It has also translated to site-specific work from her students, who are still dancing in their homes. In the fall, Bauer watched as students adapted their home spaces to fit their physical needs. One moved furniture out of the way, transforming her living room into a makeshift studio. Because students can’t do projects in a physical room together, they’ve pivoted to work in class and dance videos to document progress.

It’s not what she was expecting, Bauer said. Instead of a stage, she and students share a Google Classroom and digital interface. While some students still don’t turn their cameras on, Bauer said that most of them are learning and “still creating in different ways.” She added that students experiment at home differently than they might in a new pandemic-era studio, with masks, new social distancing measures, and six-foot markers on the floor. As of last wee, the city's Board of Education announced that high schoolers would have the option of returning on April 5.

Meanwhile, she’s done it with the backdrop of two kids at home. Last year, she and her spouse started homeschooling their oldest, a 7-year-old who attends Nathan Hale School, after they realized that back-to-back hours of screen time and an antsy little brother didn’t make learning tenable. In the fall, their youngest son was only 18 months and “tearing apart the house,” she said.

Now, there’s a steady routine, in which they teach life skills alongside school. Their oldest does laundry. Their youngest helps Bauer cook—"kind of," she laughed. At home, their schedules have become a clockwork: Bauer works from early morning through 2:15 p.m., when school lets out. Her spouse, NLTN Holistic Personal Training Founder Marannie Rawls-Philippe, works from the afternoon until 8:30 or 9 p.m. The boys get half an hour to watch television while Bauer cooks dinner. Then the day repeats, again and again.

“We sort of high-five and give a status update at 2:20, and we’re making it work,” Bauer said. “It’s not easy. I feel this … there’s this endurance that I’ve developed. I never thought I could spend so much time with my children.”

“Everybody's hard is hard,” she added. “No doubt. But we’re okay.”

“They’re Stronger Than We Know”

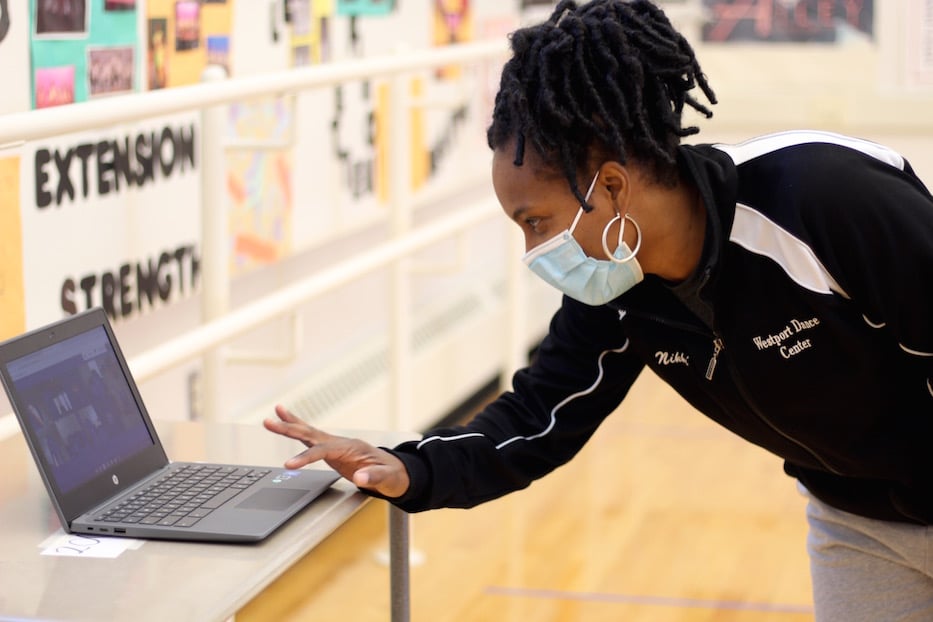

Across the district, teachers are working with their students to make the most of online learning, which has continued for some families even as elementary and middle school students head back into their classrooms. As a teacher at Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School (BRAMS), Nikki Claxton has learned to split her time between home, where her son has been learning remotely, and a mostly empty studio at the school. As of this month, both fifth graders and some middle schoolers are back in the building.

Three days per week, she heads into school, where a large, mirrored studio waits for her to turn on the lights and set up a laptop and a speaker. Long before it was announced that students would return to middle school, BRAMS staff prepared their classrooms for social distancing. Lines of tape mark the floor of her studio, so dancers can socially distance if they return.

Like Bauer, Claxton tries to make time for the social interaction students are missing. On “Wellness Wednesdays,” she has given dancers the option to learn extra choreography for special performances at the school, including most recently Black History Month. On Fridays, she teaches from home and opens the class up to discussion and dance history.

“If it’s a day where they want to talk about just life or just want to talk to each other, I allow for that as well,” she said. “I know that part of school is missing, so I allow time to just, talk to each other and have a normal day as we would at school as well.”

She said that she’s struggled most with the lack of physical contact with her students. Prior to last March, her classes meant being together in a room and on a stage, and working through choreography that told a story. On a screen, that work is arduous and sometimes confusing. Claxton can’t correct her students’ positions with a quick touch. Some of them struggle with verbal commands, especially when they include right-left directions.

Dancers at BRAMS during a special Black History Month performance that streamed live Feb. 25. Screenshot via Vimeo.

After almost a year, she’s noticed that almost none of her dancers have enough space to do a full dance. She still finds the school eerily quiet, although less than it was before the fifth graders returned.

“I’m a very hands on person, and children are too,” she said. “I’m used to the noise in the hallways, and the chatter. And I know if I’m missing that, the kids are too. It’s so much easier to help a student that’s right next to you—especially one that’s new to dance. You can touch the foot. Place the hand. Turn the head. On the computer, direction is hard. For children to dance inside for performance, it’s hard.”

Her son, a seventh grader at BRAMS studying visual art, has been learning remotely since last March. Claxton said she feels lucky: he’s old enough to learn independently, and has met hours of remote school ready to tackle his classes. With attentive teachers, he’s been able to stay on top of classwork and earn high honors with distinction. He works in a separate room, with a study station set up for classes.

“They’re teaching and I’m so appreciative of them,” she said. “I know everyone doesn’t have the same experience as I do, but it’s going well as a parent. Every household and every child I know differs.”

During the days she’s teaching at BRAMS, she checks in with him by text, and then helps with homework when she gets home. On the days she’s teaching from home, they’ve set up a system. When he has a question, he’ll come in with a hand at his ear, as if to ask if her students can hear him. If she’s teaching, she’ll tell her students to hold on, answer his question on mute, and then hop back into class.

As schools reopen gradually, she’s still experimenting with new techniques that keep her students safe. For Black History Month, several of her students learned choreography that they recorded in masked, socially distanced shifts at the school. Both she and fellow dance teacher Hannah Healey explored the possibilities of video, including montages of Barack Obama and Kamala Harris that appeared after a cover of Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come," performed by Healey's students.

In a video for “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” a handful of Claxton's students appear on the stage, masked and kneeling with their heads down. Each wears a shirt emblazoned with a raised fist that has now become synonymous with the Black Lives Matter movement. As vocals rise in harmony, students lift their bodies skyward, arms leading the way. There are only four of them present—but it’s the first time they’ve danced together in a year.

Claxton added that she feels fortunate—her family is healthy. Her students are healthy. In honor of her current students and the eighth graders who never got a final performance last year, she’s trying to plan an outdoor piece for later this spring, set to the song “A Brand New Day” from The Wiz.

“The joys are being able to get up every day and still do what I do,” she said. “Because I love it. I still love teaching. And I’m blessed that I’m able to go into my classroom and see the kids come online—the girls in their leotards and tights and the boys in their sweatpants—and they’re ready for class. Every day. They’re getting up and coming to class. When you’re home and you can be in your bed … But they’re up. We’re laughing, and we’re smiling, and enjoying the art of dance together. We’re creating together, and that’s one of the biggest joys.”

“The joy is that I have life,” she added. “The kids are okay. They’re stronger than we know. And even despite that, they’re working towards school. And they’re gonna be better for it. I tell them ‘Look at this. You’re going to be able to get through anything.’”

“I Just Have To Keep Pushing”

.jpg?width=933&name=CT_Capoeira%20-%2012%20(1).jpg)

Julien Kanor on the New Haven Green in May 2019. Lucy Gellman Pre-Pandemic File Photo.

Outside the district, freelance dancers and dance instructors have also been scrambling to push the boundaries of the medium while staying financially afloat. In Branford, Julien Kanor has spent the last year cobbling work together between Guilford, New London and the digital realm. Like Bauer, he and his partner are doing it with two young kids at home.

Prior to March 2020, Kanor was teaching modern and contemporary dance for Elm City Dance Collective, a New Haven based company of which Bauer is a co-founder. He and his wife, the dancer Erin Von Hofe Kanor, were also scheduled to teach classes in nearby Orange. When Covid-19 hit the state, those classes were cancelled. Like thousands of artists across the country, they watched months of work disappear overnight.

Von Hofe Kanor looked to her translation work, which has continued during the pandemic. Kanor began sending out resumes and scouring the landscape for digital classes. They also turned their attention to their two young children, an eight and three year old who were suddenly at home all the time. While their youngest had not yet started nursery school, their oldest was not used to being remote.

“I try as much as possible to find other things,” he said. “To try to find a way to make it work. I just keep pushing and sending resumes. Sometimes I get really lucky and sometimes I get something good. I just have to keep pushing.”

Early in the pandemic, Kanor started teaching a playful movement class on Instagram and Facebook Live. At breakfast and lunchtime, his son would often join him, and transform into his young, unexpected assistant. At times, Kanor said, the setup seemed hectic—he tried using his daughter’s room for privacy, because the family’s living room is in between bedrooms, bathrooms, and the kitchen. Sometimes he rolled with the kids joining in.

As weeks turned into months, he also picked up a fall semester class at Connecticut College in New London. Because the class was in person, Kanor said he immediately began thinking about how forms of contemporary movement—contact improvisation, for instance—worked with social distancing.

The semester was one steeped in twin pandemics: classes were temporarily disrupted by a scholar strike prompted by ongoing police violence. In the class, masked students were cautious not to get too close to each other. Then there were weekly Covid-19 tests, which meant Kanor arrived home late one day each week. The final weeks of the semester were remote. On the days that he was teaching on site, he recalled scrambling to prepare breakfast and have an easy lunch set up for his kids as his wife juggled work and childcare.

“It can be challenging sometimes, but I’m always open for challenge,” he said. “And so, it’s a good challenge. It’s an art to find something for the class to do together, and an art to keep them motivated through the screen.”

Like many artists in the pandemic—and many before it too—he has become a master cobbler. He recently picked up work teaching in-person acro-dance to preschoolers at a spot in Guilford. He’s offering remote French lessons through the New Haven based language school Aux Trois Pommes. Still the year feels precarious: he and Von Hofe Kanor are constantly looking to see what new relief is available to them.

He added that he’s struggled with the social isolation of the pandemic. Kanor grew up in Guadeloupe, to which he returns every few years to see his parents and relatives. He has a large family, with cousins and siblings whose kids are now the same age as his son and daughter. After securing his Green Card last year, he had a trip planned—but it was scheduled for spring 2020. He hasn’t been back for almost four years, in which he said his son’s French has grown by leaps and bounds. His mother last visited Connecticut two years ago.

“That’s one of the things that’s really kind of sad,” he said. “I really want my kids to be able to experience Guadeloupe … we’re really hoping for them to be able to play together [with their cousins]. They’ve never been able to experience that. I’m really wishing that all the family could have this. But hopefully soon.”