Poetry | Arts & Culture | COVID-19 | Elm City LIT Fest

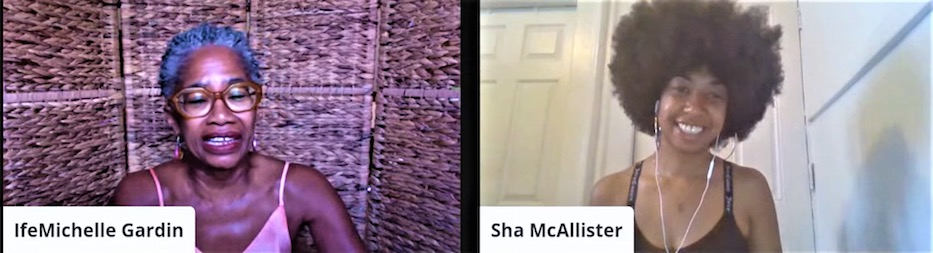

| Screenshots from Facebook Live. |

“In our culture, a dad can leave,” Shamain McAllister took a deep breath. “It’s only when a mother’s gone that reality sets in—we can create villages, yes, but being able to call your mom is priceless.”

Black representation, motherhood and resilience set the tone Sunday evening, as Elm City LIT Fest premiered its fifth podcast installment, “The Spirituality of Writing Poetry” with New York-based poet Keisha-Gaye Anderson and Connecticut-based poet Antoinette Brim-Bell. Festival founder IfeMichelle Gardin and Co-coordinator Shamain “Sha” McAllister moderated the event over YouTube and Facebook.

The duo manages the Elm City LIT Fest beside Co-coordinator Emilie Mayo. The program is produced with Baobab Tree Studios and multiple community partners. Sunday's discussion covered gender roles, racial relations, and mental health in the Black community.

“It’s a happy Sunday to celebrate the literature and literary artists of the African diaspora!” Gardin began. “We’re based in New Haven, Connecticut, but we’re global … as everybody else is in this time of pandemonium."

"I created this forum because it’s so important for our voices to be heard, so important for our continuation and inspiration—and ladies, we are so full tonight,” she later added.

Modeled in homage to both current Black authors and the Harlem Renaissance, the Elm City LIT Fest seeks to elevate Black voices across the African diaspora. In the future, the group aims to form an “African Diaspora Artists Collective” in the Greater New Haven region to keep that sentiment alive year-round. The podcast is part of a virtual shift Gardin has made in response to COVID-19.

Sunday, McAllister opened the discussion with a poem about motherhood.

“Miss Keisha, Miss Keisha, Miss Keisha—the poem ‘Stones!’” McAllister opened with a smile towards Anderson. “I can’t read every line on this, but I’ll just read a little bit."

shape thoughts / that forge a new world / from our burning hearts / destroy the illusion / custom fit for our vision / imitations of life / clowning at the risen / stand on the foundation / of my soul / my children / and make me molten / once more / so I can explode / into new worlds / paint colors / your eyes can’t see/set the captives free / set the captives free

“It took me back in time, and I just felt a beloved spirit wash over me!”

“Thank you! What a compliment!” Anderson replied. “For me, this really is talking about something big—women and their power of creation. Quite literally, we can create children, but I feel that in our role as mothers, we are inventive and creative in certain ways, sort of like making something out of nothing.”

Anderson recalled the matriarchal ingenuity in her own family. She’d learned from the best, she said: her mother wore a cool guise of blunt practicality throughout her life. It wasn’t insensitivity—the facade hid a deep desire for Anderson to adapt, persevere, and overcome. She’d need all those things as a Black woman in a white man’s world.

As Anderson reminisced, a lone figure filled her mind’s eye—her grandmother, who struggled with Alzheimer's later in life. Her mother told of her own mother’s ingenuity. She’d been barred from everything beyond a second-grade education. Her great grandmother spent her life as a domestic worker to feed her family, and her grandmother spent her life as a dressmaker and seamstress.

The household never wanted for anything. Anderson’s grandmother sewed her daughter’s wedding dress with no patterns. She’d sent an infant Anderson Raggedy Ann dolls and doll dresses, mailed from Jamaica to New York. She “made it work,” wanting nothing more than for Anderson and her mother to live a better life than she had.

That desire inspired Anderson’s book Gathering the Waters, published in 2014. The poetry collection is a current of generational struggle and trauma—the water, while cold and biting, still cleanses Anderson’s soul.

Her 2018 publication Everything is Necessary has a cover adorned with Anderson’s childhood face; that face would overcome the trials and tribulations set upon it. Anderson’s victory and her family’s sacrifices gave her agency. She will publish another book, A Spell for Living, that explores that agency later this year.

“You know, that’s how Black women, we are naturally,” Anderson remarked. “A problem approaches us, and it’s, ‘Okay, well, how are we going to flip this, because this isn’t working, so we need to figure out how to make it work. Throughout time, our ancestors have made it work and have blossomed and excelled with little to nothing at times.”

McAllister launched from Anderson’s assertion onto the feminine virtues found in Brim-Bell’s own work. Brim-Bell began by breaking down These Women You Gave Me, her 2017 poetry collection set in the Garden of Eden. The title represents Adam’s cries to God and the only male voice found in the book. The narrative is an interplay between the perspectives of Eve, a personified Garden of Eden, and the controversial theological figure Lilith, or “first Eve.”

Brim-Bell said she was initially nervous about publishing the work due to its subject matter: she felt it would be far too easy for religious institutions to admonish a woman’s perceived heresy. But she believed in the collection, and pressed on.

“A lot of how women see themselves are because these iconic figures are in front of us. They have shaped the patriarchal perspective of what a woman is, and subsequently, we have to fit ourselves into that mold,” Brim-Bell said. “I grew up with this whole notion of how Eve caused The Fall of creation, and it was because she wasn’t submissive or obedient. I wondered what these literary women would say for themselves if they had an opportunity to tell their stories because, oftentimes, we don’t get a chance to tell our stories.”

Brim-Bell discussed her research writing the book. Both Lilith and Eve were cast in a negative light wherever she looked. Lilith’s sin had been her insistence that males and females were equal. After being cast from paradise, God created Eve in her stead. She was born with a childlike mind—and curiosity. Scholars claimed her inquisitiveness caused her to disobey Adam and God. Medieval and Renaissance painters depicted Eve as a foolish beauty. Lilith received worse—she was a demon with teats filled with acrid poison and a penchant for killing young children.

“It’s interesting because when Lilith left Adam, he says to God, ‘That woman you gave me ran away.’ When God asked him, ‘Why did you partake of the fruit?,' Adam said, ‘That woman you gave me gave it to me.’ Both times for both wives, we have Adam pointing the finger. I wanted to give the two the space of a global conversation, what it truly meant to be a woman at that particular time in those particular positions with the Garden as an objective observer.”

Brim-Bell’s other publications have continued to examine female psychologies. Her earlier 2013 Icarus and Love was an exercise in caution—love’s dopamine means nothing after it melts your feathers. Brim-Bell learned the hard way that flying too close to the sun burns—her 2009 Psalm of the Sunflower stemmed from her divorce.

The idea of a sunflower came to Brim-Bell after listening to an episode of Science Friday on National Public Radio (NPR). She learned that a dying sunflower is “so intent on living” that it faces it’s buds toward the sun and buries its roots eight feet underground, searching for water. Eventually, pain becomes a tale of a woman’s slow resilience and growth. It was Anderson’s matriarchal tenacity. It was the new tattoo on Brim-Bell’s foot.

A question from the livestream’s chat turned the conversation away from literary analysis and metaphor towards philosophy. A viewer asked: “This event is called the ‘Spirituality of Writing Poetry.’ Does spirituality refer less to religion and more to faith in general?”

Brim-Bell jumped in, noting that the four needed to separate spirituality from religiosity. For her, institutionalized religion is a place to take and share personal beliefs or spirituality. She acknowledged that the concept of free sharing was rather idealistic, citing her own unorthodox views on the book of Genesis.

McAllister nodded, voicing similar concerns. Hearing Brim-Bell speak on Adam, Eve, and Lilith brought back her own insecurities sitting in church, feeling responsible for man’s fall because she was born a woman.

Brim-Bell reminded her not to let religiosity taint her spirituality, noting that original sin was theologically the catalyst for human salvation and redemption. Soon, Anderson spoke, using the analogy of music to reaffirm the group’s points for viewers; she had turned from her Catholic upbringing to African traditional religions more than twenty years prior.

“Everybody on earth can appreciate music,” she said. “To me, that is akin to spirituality—the spirits move through people. You don’t need to know anything to connect with nature or energy. Everybody reacts the same way when a baby is born, the wonder of it all. Religion is like learning to write music. There are rules, and you’re learning to do a specific thing and speak a shared language. At the same time, it’s not realistic for everyone to do the same thing. If you look around the world, everybody does things differently.”

McAllister pivoted her focus to Brim-Bell’s salvation, asking what role redemption could play in postlapsarian living. After some deep thought, Brim-Bell spoke. She split McAllister’s prompt into two questions— “Is redemption possible?” and “Can it happen now?”

Fixing her eyes on racial relations, Brim-Bell explained pertinent definitions of “redemption” and “repentance.”

“For redemption to come, there’s got to be some real repentance,” she said. “Repentance means that we have to own up to what we’ve done, decide not to do it again, and make restitution. If we’re thinking reconciliation between the races, there has to be some owning up to some ugly truths some steps forward.”

“We’ve got a lot of institutionalized obstacles that keep people from being everything that they can be, and what we have to realize is that the country is not going to be everything it can be until everybody within the country has the opportunity to be their very best,” she continued.

“Nobody can sit on the sidelines with their arms crossed—everybody’s got to get in there and find out what their places and in the reconciliation and then and only then are we going to see any true redemption.”

Brim-Bell scorned America’s “rugged individualism,” calling for a collective change towards social good. Still, McAllister acknowledged just how difficult attaining Brim-Bell’s brand of redemption would be.

“We must sit in that uncomfortableness and understanding of those ugly truths” McAllister said. “It has to be seen how it happened—they can’t be sugarcoated ’cause it hasn’t been a sugarcoated experience for us. We can’t just move on from those problems. They’re not in the past. They’ve transformed into something else, transformed into mass incarceration, economic disparity, voter suppression, and has transformed us into people who are forever changed by this trauma and pain.”

“I do think that we’ve always been resilient and forgiving people,” she added. “Black people, folks can do anything to us, but we always find a way to smile and a way to turn around—we can tell a joke out of the most horrible situation, and it still be funny because there’s always light in that darkness.”

After a pause, Brim-Bell sighed. Though she agreed that the Black community was resilient, she knew that its pain had become “all too buoyant.” She recalled how she worries when she lets her son—a figure about whom she also writes—borrow her car. She always points out where the registration is in the back of the glovebox. Sometimes, she wants him to lay it on the seat, so that he doesn’t risk sticking his hand into a space hidden from the driver’s side window. She does it as a Black female educator, a role model for her non-white and white students alike.

“When you try to hold a beach ball underwater, you can only do it for so long before it just breaks through and pops up,” she said. “That’s where we—that’s why the people are in the street. The pain just can’t be held down any longer. We need to start to heal these wounds once and for all. This COVID stuff, the economy, and race are a perfect storm—it’ll either make us or break us.”

Anderson looked to Black pain and societal reconciliation under the frame of privilege in the United States. She pointed out that Black people have been historically short-changed and disenfranchised in a game of “who gets what” based on race and identity. She praised this “perfect storm” of COVID-19 and violent, structural racism for allowing homebound citizens to reflect.

In the information age, no one can feign ignorance about systemic injustices or police brutality, she added. No one is unaware of the names George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. She channels that by writing about her forgotten Black sisters, the ancestors she does not know by name. She said she basks in their traditions and unearths what enslavement took from them. She approaches life from the eyes of a student. She makes sure her children do too.

“The country is poised to not be a white country in the next 50 to 100 years, so there’s things we need to like look at,” she said. “These are bigger conversations about economics and identity, but what I will say is that our suffering is required for our present structure to function.”

McAllister explained that she lost her mother in 2016. She’s been building a “village of mothers” ever since. Gardin was recently added. Brim-Bell smiled at this; Anderson noted that McAllister follows a doctrine their African ancestors taught long ago. It takes a village to raise a child.

We carry our dead with us, Brim-Bell read as the event reached its conclusion. Rain will not stop because we will it / A dead messenger does not change the truth / the truth instead settles itself inside us / there is no antidote for the grief that ails / no song drowns out a mother’s wail / no force can pull up mothers’ fists from the Sky / We bear the sudden sandstorm / Grit our teeth

I hear you mom, Anderson later read. I love you for what you endured to bring me here / But I create words / it is my job to dream / imagine for those bred to be blind / love is my palette / I fear no man / I use this body like a chisel/ a shovel / a machete / and I will never stop until I am the biggest dream I can imagine / because the prescience wasn’t beat out of me / and I’ve had enough food and books and the anonymity of a big city to remember what you have been forced to forget.

Watch more discussions from Elm City LIT Fest here.