Culture & Community | Arts & Culture | Elicker Administration | Arts & Anti-racism

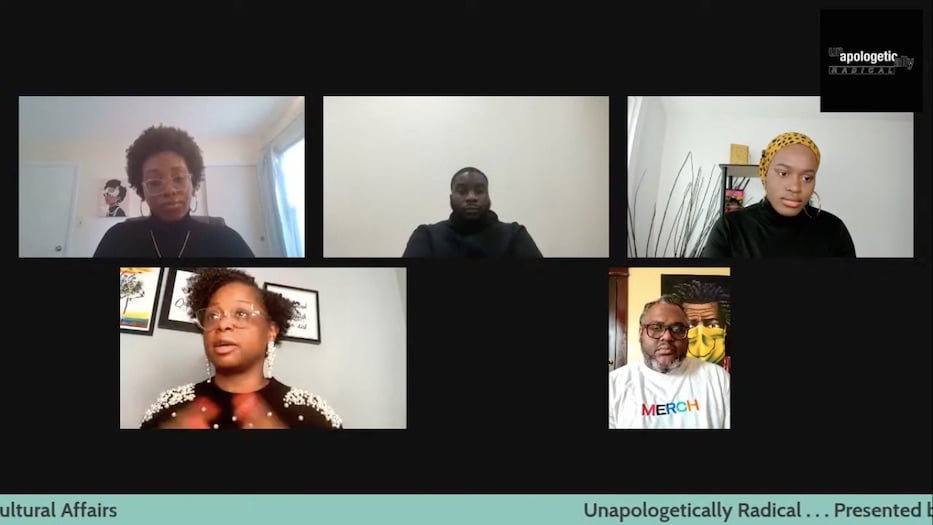

Screenshot from YouTube.

When Aaron Rogers saw a resource gap in his city, he turned to arts and culture to fill it. Now, he's using that model to empower young people growing up in the place that raised him.

Saturday, Rogers was one of five participants in “Street Civics,” one of three panels at the city’s second annual Unapologetically Radical conference. During the 40-minute discussion, panelists took on meeting the demand for Black-centered mental health care in New Haven, creating safe spaces for Black youth and using culture as a bridge to greater opportunity. The panelists included Rogers, founder of The Breed Academy; Black Haven Founder and Executive Director Salwa Abdussabur; artist and curator Andre Rochester; and trauma therapist and Stop Solitary CT board member Kevnesha Boyd. School Social Work Solutions Founder Jocelyn Sailor moderated the discussion.

The conference, held online due to Covid-19, is the work of the city’s Department of Arts, Culture, & Tourism. In addition to “Street Civics,” panels included discussions on building community safety and generational wealth, the critical race theory debate, and a keynote address from activist Tamika D. Mallory. The archived livestream is available here.

“As an artist, when you see your peers, the artists that you love and care about, the stories that activate you—we saw that during the pandemic,” Abdussabur said. “Art became our lifeline.”

To participate in “street civics” is to take direct action in one’s community, either through “grassroots activism, community organizing, or civic engagement,” Sailor said.

Through their respective grassroots organizing, all four panelists pointed to arts, culture, and creative storytelling—as well as affinity spaces and trauma-informed healing—as a way to bridge a historic resource gap in the city. In New Haven, where Yale University alone owns $4.23 billion in tax-exempt properties, Black and Latinx city residents have taken the hardest, and longest, economic hit—from stable access to food and healthcare, to jobs and affordable education.

Early in the conversation, Abdussabur noted a sense of neglect among city residents, particularly young ones, who feel that the city has not shown up for them. She spoke about the birth and growth of Black Haven as a way to activate community during the ongoing pandemic. More recently, she was also able to do that as a member of the collaborative team that worked on New Haven’s inaugural cultural equity plan.

“I want to see the city of New Haven commit to showing young people in their streets, in their neighborhood—visually telling them—that we gotchu, we got your back.” she said. She proposed creating paid positions for the Black arts organizers for the work they are already doing.

The arts, the panelists agreed, can be a catalyst for providing these resources. Rochester, a working artist and teacher in greater Hartford, has centered emotional honesty and vulnerability in his practice for the past 25 years. Many of his works are based on his own emotional experiences with police brutality and the long legacy of slavery in the United States. It’s this kind of openness that he hopes will facilitate increased dialogue about Black male emotion.

“I’ve shared my own vulnerability with you,” Rochester said, referring to the paintings he shows in galleries. “I’m making it safe for you to do the same.”

He pointed to his own experience as proof that the arts can be a tool for mental health, education and increased communication. Several weeks ago, Rochester was teaching at a primary school. A teacher had labeled a certain boy with “behavioral issues.” The boy’s behavior during the lesson was far from that label, he said.

“Every time he does something artistic, he’s locked in,” Rochester said. “There’s no problems, no nothing.”

Multiple panelists spoke on the importance of mental health, painting their own portrait of street civics in the process. Boyd, who grew up in New Haven and now lives in Hamden, noted how generational trauma can leave its imprint on a community for hundreds of years. In particular, she said, that means the often-unspoken trauma that springs from the forced migration and enslavement of Black people and the centuries of torture, family separation, and economic depravation that followed.

Her private practice, called Quality Counseling, grew out of a belief in intergenerational healing. She estimated that “I get about 10 referrals per week for people looking for a Black therapist,” she said.

Through her own work, she’s seen firsthand that there are more Black people, as well as other people with historically marginalized identities, in need of professional care than there are adequately trained, culturally responsive professionals. In addition, access to quality mental health care is still often perceived as a luxury good, when in reality, it’s a necessity. That’s led to people dropping out of therapy because they can’t afford it.

“We really have to advocate for better laws, in terms of health care, so people can afford it,” she said.

“The fact that we have excelled, and the fact that we come together, and the fact that we thrive and we love and we have not sought revenge after the harm that has been done to us, I think, has to be a testament to the fact that … we’ve always been healing,” she said. “We’ve always been doing the work.”

All four panelists also agreed that the arts can be an educational tool. As a young person in New Haven, Rogers said he considers himself fortunate to have been a musician. Playing at church every Sunday exposed him to gigging as a source of income. Before he learned to gig, the need to provide for his family was high, and out of necessity he resorted to gathering the basic living essentials by “dabbl[ing] in the streets,” he said.

Now a multi-platinum producer who has worked with artists such as P Diddy and Jennifer Lopez, Rogers is adamant that professionals like himself return to the community and use their success to lift up its members. In 2009, he co-founded Breed Entertainment with Rashad Johnson. In 2019, he used a grant from the Connecticut Office of the Arts to grow the Breed Academy’s music production and music business programs, teaching students the skills that he had to learn on his own.

“People think they have to make it out first and then come back and help,” he said. “ I think that’s the worst idea ever.” It’s possible to still be building one’s career and simultaneously passing down wisdom to others.

The Breed Academy’s mission is to teach young people business and entrepreneurship through music. “A lot of children and artists from our community get taken advantage of because of a lack of knowledge,” he said. Through education, they can provide for themselves in a system that has failed to give them the resources to do so.

“We cannot as Black people expect the oppressor to be our savior,” Boyd contended. “That means we’ve got to save ourselves and that means we’ve got to create the spaces ourselves to save our people.”

And there’s also a surge of momentum.

“We’re in the middle of a black Renaissance,” Abdussabur proclaimed. “This work’s gotta get done.”