hip hop | Juneteenth | Music | Neighborhood Music School | History | Neighborhood Cultural Vitality Grant Program

Dancer Reina Pelle. Lucy Gellman Photos.

The theme from S.W.A.T. had already turned the air electric when Oni Davis half-leapt into the circle, knees bending instinctively to the beat. She lifted her arms and let the music do the rest. Bass and percussion thrummed through the room, joined by a chorus of Ayyy! Ohhh! Ayyy! Ohhh! that seemed like it had always been part of the track. To the side, DJ Tony Tone did alchemy on the turntables, reaching for another record.

In the center, Oni became a blur of blue and lilac, her sandals and sweatshirt moving with her as she danced. By the time she eased back out and Bobby “Pheenix” Stewart entered the space, each body in the room was a live wire, waiting for just the right moment to join in.

That infectious, explosive and often dance-worthy joy lived at the heart of the sixth New Haven Hip Hop Conference, held all day Monday at Neighborhood Music School on Audubon Street in New Haven. The culmination of a song- and dance-filled Juneteenth weekend, the conference received support from the Artsucation Academy Network, the Africana Studies Department at Southern Connecticut State University, and New Haven’s Department of Arts, Culture & Tourism. Earlier this year, it was also the recipient of a neighborhood cultural vitality grant from the city.

“Hip hop is something that you do,” said Dr. Hanan Hameen-Diop, who has organized the conference for over half a decade. “Hip hop is not an outfit you put on. And this is the hip hop I grew up with. You see this community right now? This is hip hop.”

Dr. Hanan Hameen-Diop and her father, the musician and educator Jesse "Cheese" Hameen.

Over eight hours, it became a chance to go deep on the history and evolution of hip hop, the Bronx-born genre that turns 50 years old this summer. In addition to graffiti tutorials, interactive music workshops, and presentations from the Cold Crush Brothers and Def Jam legend Nikki D., it included multiple panels on arts and education, film screenings and a drum and dance workshop that closed out the night.

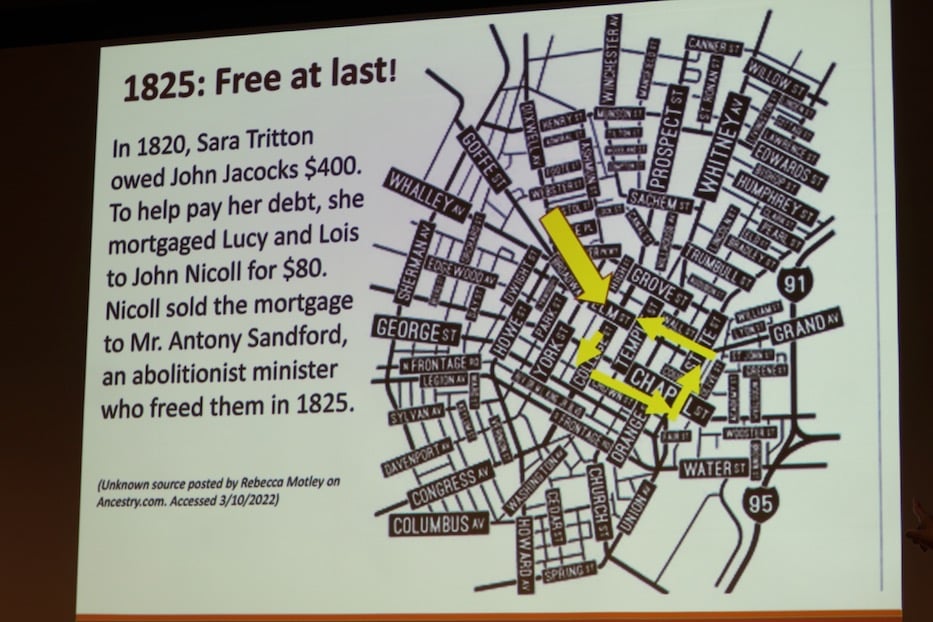

From its beginning, speakers focused on not just the importance of hip hop as a genre, but the way the Black diaspora has uniquely formed and shaped it. Early in the day, historian and author Jill Marie Snyder took the stage to tell the story of mother and daughter Lucy and Lois Tritton, the last known enslaved Black people to be sold as property in New Haven.

Prior to 1825, the two were traded as financial collateral—rather than people —in an $80 mortgage from Sarah Tritton to a man named John Nicoll. In March 1825, Nicholl sold the two at public auction on the New Haven Green. Abolitionist Anthony P. Sanford emancipated them immediately after completing the sale.

But New Haven rarely sits with that uneasy history. Back then, Snyder explained, “it was the custom to parade” enslaved people through downtown New Haven, where streets now bear the name of known slave owners, men who voted down a proposed Historically Black College in New Haven, and Eli Whitney, whose invention of the cotton gin helped extend chattel slavery in the American South by decades.

Pulling up a map, she traced a route that wove from Broadway Avenue down College Street, across Crown and Chapel Streets up State, and then back down Wall Street. In the room, attendees could hear a number of sighs, people drawing air through their teeth and noses.

While many things have changed for the better, Snyder said, some are surprisingly close to what they were at the turn of the 19th century. The city, where slavery was not formally abolished until 1848, still bears the scars of de facto segregation, redlining and urban renewal.

“The housing patterns that you see today, those housing patterns go back to the 1800s,” Snyder remarked. “Some things haven’t changed that much.”

When Snyder concluded, Hameen-Diop stressed the importance of understanding New Haven’s own Black history—the good, the bad, and the ugly—in understanding the full breadth of the diaspora, and the mark it left (and continues to leave) on cultural expression across the globe. As a kid growing up in the South Bronx, she learned about the depth of Black culture before she even had a name for it, she said.

In her childhood apartment building, for instance, she could go to one floor, and might smell arroz con gandules that Puerto Rican and Dominican families were making for dinner. One floor up, that same dish would be known as beans and rice, spiced differently depending on where in the country families had moved from. A few floors up, it was Caribbean-kissed rice and peas. All originate from the diaspora, she said.

“When we said Black people, we meant all of us,” she said. “We was together. We are all the descendants of those who were enslaved. It’s the drums. It’s the dance. It’s the storytelling. It’s the griot. We are all the same people.”

DJ Dooley-O Jackson with a blank canvas.

Opening a first-floor door, she guided participants outside into the bright morning, where the Park of the Arts was covered with wood chips that gave off the soft, sweet smell of cedar as feet padded across them. Beneath a large tent, DJ Dooley-O Jackson unzipped a duffel bag full of spray cans, and prepared to get to work on a live graffiti demo.

“Now,” he said, lifting a cool blue can of Montana spray paint as he mapped out the letters to Juneteenth on a rectangular white canvas. “Every spray can is not a good spray can.”

Talking attendees through his first outline, Jackson dipped into both his process and long history of graffiti, which became part of his life over four decades ago. When he was still in middle school, Jackson recalled, he would visit what was known colloquially as the “Graffiti Hall of Fame,” a sprawling, unauthorized canvas at the Jackie Robinson Educational Complex in Harlem.

It was there as just a teenager that he got his first taste of graffiti, and realized that he loved and respected the art form. As he spoke, listeners taking out their phones to record every word, he added purple and orange, until suddenly the canvas was slick and glistening, and popping with color. As she watched, dancer Reina Pelle and organizer Marcey Lynn Jones joked that he had chosen their favorite colors on purpose.

For Jackson, the art form was intoxicating. He loved music videos with sprawl of graffiti in the background and murals that burst into color with the whisper of an aerosol can. At home in New Haven, he started experimenting with artmaking himself. By 1989, he loved it so much that he had turned it into a show called GTV—Graffiti TV—on Public Access Television. He and others formed a crew called The Soul Brothers, with ground rules built on respect and a sort of code among artists.

“You get to the point where it’s an addiction,” he said. “Everybody had their own style. I started creating before YouTube, so it means a lot to have my own thing.”

During those years, stretches of Henry Street were “the graffiti playground,” he remembered with a smile, reaching for a can of black, and another of red. Years later, he would return to that site with artist Alberto Colon for an homage to the late Maya Angelou. With other artists and help from the neighborhood, the two memorialized her there nine years ago, just a week after she died in May 2014.

The spray cans hissed their assent as he chatted and worked. He remembered doing graffiti in the winter, when the weather was so cold that the can would stick to his hand. Attendees laughed as he told another wintertime tale, in which a police officer caught him in the midst of tagging, and his response was to run. As he and his friend tried to book it, the two were caught in a blizzard. In the intimate group, laughter bubbled up between two benches as he mimed running in slow motion.

“Being embraced by New Haven’s art community is really very important,” he said. “I’m still looking for something big to do.”

He added thick outlines in black, then searched through his bag until he’d found a can of white paint he was looking for. It fizzed and whistled as he added quick accents to the letters, and then two bright white starbursts. He jumped back to the present and backed away from the canvas for a moment, checking out the marbling of orange and purple paint.

“Okay,” he said. “Okay. I’m happy with how that turned out.”

You Don’t Stop

DJ Tony Tone of the Cold Crush Brothers.

Back inside, DJ Tony Tone walked the group through the history of hip hop, which was born in a rec room in the South Bronx in August 1973. As he introduced the elements of the genre—DJ, emcee, graffiti, break down, and knowledge of self—he gingerly lifted Manu Dibango’s “New Bell” from a crate of records he had brought from home, and introduced the concept of scratching.

“You see all that I’m doing?” he said as attendees came in close, some pulling their chairs in to the table until they could see the album covers. They looked over his hands as his fingers gingerly reached down, and stopped and started the record. “This is figuring out how to work the turntable while it’s still moving.”

He moved to the importance of the break, the shorthand for a song’s danceable and rhythmic core, while flipping through records with one hand. Starting with early Jackson Five, he mixed in The Temptations, showing in real time the way disco fed into hip hop. His hand fluttered over the turntables until exactly the right moment, and then it was all muscle memory.

Imagine it was the 1980s, he said. “Everybody’s dancing in circles and we’re just waiting for the break.” He smacked an invisible drum as the percussion came down.

As he pulled out new titles, bouncing to the sound himself, Tony Tone traced how hip hop as people know it today—maybe most immediately from The Sugarhill Gang’s 1980 “Rapper’s Delight”—does not always make room for the depth of disco-, Motown- and soul-drenched sound that all became early influences in the genre.

He cycled through The Jackson Five, Marvin Gaye, Cat Stevens—all people and groups that “you might not consider hip hop,” he said. Pulling Stevens from his record collection, he smiled a little to himself before laying down the vinyl.

“He was probably just vibing himself,” he said. “But we heard it and we accepted it as hip hop.”

He described how he and members of the Cool Crush Brothers would help a party wind down, setting the needle down on Heatwave’s “Always and Forever.” On one side of the room, a couple stood and slow danced to the sound.

“At any point in the party when it was really hype did you ever slow ‘em down?” Jackson asked from where he sat, listening intently, in the second row.

“Oh yeah,” Tony Tone said as he mixed in Big Daddy Kane and, minutes later, Cymande’s “Bra.” He brought the set to its end with Chic’s 1979 “Good Times,” which he recognized as unique not just for its appearance on “Rapper’s Delight,” but for its length. The full song is over eight minutes long, at a time when most records stayed closer to two.

“Now remember, you gotta cut it so that people can dance,” he said before turning things back over to the organizers.

Hameen-Diop stepped to the front of the room, cheering DJ Tony Tone on. She invited attendees to get out of their seats and come in closer, just as they had during the DJ’s demo.

“So what do you think comes next?” she asked aloud. “We got the graffiti. We got the music. Where do we go now?”

“Dancing!” somebody shouted from the third row.

“Dance!” she replied, a smile bursting across her face. “People came to the party for the dancers.”

Hanan Hameen-Diop.

She drew people into a wide circle, ushering in the elements of breakdancing. From the side of the room, Pheenix emerged, thick beads swinging around his neck. He slid onto the stage, making it his own as he dropped into a windmill, kicked his legs into the air, and sprang back up onto his feet. Time seemed to freeze and unfreeze around him.

The night before, Hameen-Diop explained, he’d been dancing on Temple Street, beneath the lamplight when she heard his music and stuck around to dance with him. When she invited him to Monday’s conference, it seemed like a no-brainer.

Back in the circle, Hameen-Diop invited attendees to join in. At first, there was silence, people shoulder-shaking, bouncing, and bending instinctively to the music on the periphery. Hameen-Diop encouraged them with more history of the form. Rather than biting—dancers copying each other—she just wanted to see people move in a way that made them feel good and honored the genre.

“Everybody looked different,” she said, adding that she’s not down with new forms of social media focused on copying the same dance trends over and over again. “Everybody had their own style. It’s about doing your own thing.”

“When we were growing up, that’s what made you a rapper,” said Dr. Siobhan Carter-David, a founding member of the Africana Studies Department at SCSU. When she listened to early hip hop as a kid in New York, artists wrote their own music. There weren’t layers of writers, followed by layers of aggressive autotune.

The nerves lifted. Dancers eased into the circle one by one, each with their own personal choreography. When it was Oni’s turn, she rocked it out, letting her shoulders and toes lead the way. “Ayyyy!” the room exploded around her. She stepped back and Pheenix, who later said he’s been dancing since he was a kid, cycled in, dipping low to the ground before

“Who’s next, let's go!” Hameen-Diop exclaimed, never breaking with the beat. Funky bass rolled beneath her. Carter-David answered the call, and the circle kept going, the rhythm and dance unbroken.

Bars Not Bullets

Nikki D., the first female emcee signed to Def Jam.

It flowed right into a keynote from emcee Nichelle Strong—more widely known as Nikki D., the first female emcee signed to Def Jam—and subsequent youth panel, focused on the reclamation of hip-hop culture and the need for more music that unites people and community, rather than divides them.

Born in New Jersey and raised in New Jersey and later Los Angeles, the artist remembered finding her musical footing at an early age, somewhere between services at Newark’s New Hope Baptist Church and Kool Moe Dee’s “How You Like Me Now.” When she was 12, she started writing rhymes and learning to freestyle, a skill that has served her as an artist for decades.

I’m young and I’m sweet and I’m fresh as could be and not a female in the place can get with me, she rapped a cappella with a smile, and the room moved and clapped to the sound. Because I dress to impress, always look my best, if you think I’m lyin’ ask the IRS …

To be an artist then, she said, a person had to listen to other artists and respect the genre. For her, that meant Kool Moe Dee, Pumkin and the Allstars, the Cool Crush Brothers and emcee Sha-Rock, who was just a teenager when she kicked off her ceiling-shattering career in the South Bronx. It was through Sha-Rock that she grew to appreciate the art of emceeing.

“We’re talking about the master of ceremonies,” she said. “He’s at the DJ booth, and everybody was chillin’ in the club, and they keepin the party going. Alright? This is our first version of somebody really speaking into the mic and giving us that energy.”

Nikki D. Dr. Hanan Hameen-Diop, and Professor Siobhan Carter-David reading from two proclamations, one from the city of New Haven and one from the Connecticut General Assembly, made to Nikki D.

She was still a teenager, and lived for that energy. From learning to emcee, she dipped into the culture of battle rap, in which artists could challenge each other to show off their craft in real time. For her, she said, that contest of skill, quick-thinking and originality remains much more involved than the disputes she sees between rappers in the current music landscape.

“It was all lyrics back then—we’d moved away from the idea of it being entertainment,” she said. “So if somebody said, I got 16 in the clip, that doesn’t mean 16 bullets. I got 16 bars. Do you know what bars are? If anybody is not familiar with bars, it is the count when you hear a beat.”

She teased out the difference between a pre-written song and freestyle, pulling in audience members to do four bars a piece off the top of their head. Back then, she said, battles were how rappers worked their differences out, selling sharp and airtight lyricism instead of the death she hears on airwaves today. She watched as people like Doug E. Fresh and Salt-N-Pepa entered the scene and made history.

Fast forward to the present, she said, and it pains her to see that “there is no more message in our music.” When she walks into a recording studio with her son, who is now himself an artist, she has to advocate for a stripped-down recording, where she’s only as good as her lyrics and her own voice.

“We never talked about killing nobody, we talked about killing you as an emcee,” she later added. “We never talked about doing nothing to your family, we talked about doing it as an emcee. Your boy, your homeboy, your girlfriend. Everything was done because we’re battling. It’s not because we actually want to hurt you.”

In part, she said, she blames the commercialization of hip hop, which happened when people realized they could capitalize on the music. But that time was also one of exponential growth. From mixtapes that got the music out, records started to enter the mainstream. While “Rapper’s Delight” may be the most prominent example—with a smile and a laugh, Nikki D. remembered buying her own copy—she said, it certainly wasn’t the only one.

Def Jam, which became her door to stardom, entered the fray. She remembered having to work harder than any of her male peers to “kick the door open” and prove herself, which she did in the mainstream with her 1991 “Daddy’s Little Girl.” The piece, which samples Suzanne Vega but is all Nikki D., put her on the sonic map.

“Here’s the thing,” she said of those early releases, dropping the first bars of “Rapper’s Delight” from memory. “You will remember this until you die, because it is our soul music.”

Members of Ice The Beef. Eliza Vargas and Manny Camacho are in the yellow and the suit respectively.

Because of the work that she and her peers put in for years—like fully cooking a recipe—she said, she struggles with the “microwave rap” that she hears today. When she turns on the radio, she hears aggressive autotune, polished takes, and musicians who don’t even know their whole pieces by heart.

She worries that contemporary rappers, who often aren’t writing their own lyrics, are selling violence and capitalism instead of tight lyricism and a celebration of culture that was rooted in community.

“I’m not mad at evolution,” she said. “I just have a problem when you remove the essence.”

She wasn’t alone in her frustration. During a panel with youth from Ice The Beef, who Tuesday night returned to the stage with their performance of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, recent James Hillhouse High School graduate Manny Camacho said he worries about some of the music coming out.

Manny Camacho, Antwain Johnson, Eliza Vargas, Nikki D., Dr. Hanan Hameen-Diop, Chaz Carmon, and Catherine Wicks (at the front).

Recently, he overheard a new track that his 13-year-old brother was listening to, that espoused gun violence. For Camacho, who has buried multiple peers and spoken at more than one vigil this year, it begets a cycle of “anger, vengeance, and violence.”

“Yes, music can be helpful, but some of the music coming out can have a negative influence,” Camacho said.

“It’s brainwashing,” chimed in 22-year-old Eliza Vargas, a graduate of Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School who has remained in New Haven as an educator. “It becomes hysterical at a point. You want to be 27 with seven homies in the grave? You want to put money on the books for your bros? But you won’t pay for school books for … your bros?”

From the back of the room, Nikki D. began applauding. “Y’all are the new leaders,” she said.

This article is a collaboration with the City of New Haven's Department of Arts, Culture & Tourism, which is supporting young writers who cover recipients of the 2023 Neighborhood Cultural Vitality Grants.

This article is a collaboration with the City of New Haven's Department of Arts, Culture & Tourism, which is supporting young writers who cover recipients of the 2023 Neighborhood Cultural Vitality Grants.