Black History Month | Arts & Culture | Quinnipiac University | Hamden Department of Arts & Culture | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism

Hip hop helped a group of Wilbur Cross High School seniors get to graduation. When Professor Don Sawyer III looks at their flowing caps and gowns, he thinks about how many more students could heal with access to the poetry, philosophy, and lyrical swerve that defines the genre.

Sawyer is an associate professor of sociology and vice president for equity and inclusion at Quinnipiac University. Thursday night, he gathered with fellow educators, scholars, poets, and musicians on Zoom to discuss the intersection of hip hop, education, and activism through the arts. The talk coincided with the publication of Hip-Hop and Dismantling the School-to-Prison Pipeline (Hip Hop Studies and Activism), which Sawyer co-edited with Daniel White Hodge, Ahmad R. Washington and Anthony J. Nocella.

The discussion was co-sponsored by the film series Ignite the Light, Elm City Lit Fest, Best Video Film and Cultural Center, the Theta Epsilon Omega Chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc., Spring Glen Church, and the Hamden Department of Arts and Culture.

“I was born and raised in Harlem, New York City, and so hip hop has been a part of my life since I can remember, and I often say that hip hop saved my life,” Sawyer said. “And so, in the work that I do with youth on campus and off campus, hip hop is the language and the culture that we exist in and that’s what we use to connect.”

Panelists included Rutgers University Professor Lauren Kelly; New Haven educator and former Future Project Dream Director Frank E. Brady; Hip Hop Association of Advancement and Education President and Co-Founder Dr. Tasha Iglesias; “The Sonnet Man” Devon Glover; and Three Rivers Community College professor and Hartford Poet Laureate Frederick Douglass-Knowles II. Sawyer likened them to the Avengers, “a super team of people who are doing beautiful work.”

In just over an hour together, each made the case for why hip hop can be a transformative tool for both education and liberation. Iglesias noted that it begins and ends with the genre itself: hip hop was born through collaboration, experiment, and explosive joy during a sweltering summer in the Bronx. It’s official birthday is August 11, 1973—just months before some of Thursday’s panelists came into the world. When she came to the medium, it was through breakdancing in college. She was moved by the community that she saw at jams.

“I realized that we were hugging, there were different generations, there was a lot of love,” she said. “It was a very different perception of hip hop than I had been taught through commercialism. So I used that energy and that passion of this culture to bring people together as an activist.”

Hip hop became a launchpad into her activism. She harnessed its power for voter registration drives. She kept going to jams. While pursuing her doctorate years later, she used hip hop as a tool for community building, working with 60 foster youth on campus. In her work with them, her research explored how hip hop’s history, lessons and practical applications translated to mitigating stress and building confidence. She found that the more she shared about the history of hip hop culture, the more students saw themselves reflected in its rich legacy.

“They felt seen, they felt heard, and not only that—they were able to think beyond what people were telling them in the institution,” she said. “Most of them were saying ‘hey, you’re a foster youth, you should be happy you’re getting a bachelor’s degree. That’s just great in and of itself.’ And I’m like: Think about graduate school! Think about the next step! What’s next? You have so much potential.”

Other panelists marvelled at hip hop’s ability to speak to the current moment across media and discipline. Brady, who worked at Wilbur Cross for eight years, said that he thinks of hip hop as a door to anthropology, sociology, and psychology, as well as to finance, literature, and poetry.

He recalled working with a student several years ago who “was called the n word through a racist encounter” with another student. It came around the same time that Cross students were planning Black History Month programming at the school. The student wrote a rap that used the word, and proposed presenting it at an all-school assembly.

Initially, the school administration said it wasn’t possible to do the full rap. The student returned to them with a PowerPoint presentation and made his case a second time. He worked with leadership to figure out a way to introduce the piece as it had been written. When it came time for the assembly, the principal introduced the piece.

“[He] did this amazing rap that really shifted the culture of the building for a little bit, because so many of the young people were listening to him," Brady said. "And I really think him taking ownership as an MC and as an educator … it really empowered his peers.”

Kelly, who is an assistant professor of urban social justice teacher education at Rutgers, pointed to the Hip Hop Youth Research and Activism (HHYRA) Conference that she and students have been organizing since 2019. When Covid-19 forced the conference online this year, students turned the space into a bi-monthly discussion series. She focused on a recent session led by students Semaj Skillings and Naomi Filipiak. The two talked about what it means to experience romantic and platonic love after almost 12 months of isolation.

She listened as students, some as young as high school, took a Saturday night on Zoom to talk to each other about the love that they had in their own lives—with friends, partners, families. They talked about couples they admired, including cousins, parents, and family members. They let themselves be vulnerable. They connected across the distance. Kelly saw the culture of hip hop working through the space.

“This work, it’s about what hip hop does to galvanize people and sort of bring us together,” she said. “And the work in the end isn’t about developing lyrics. It isn’t about rapping, necessarily. It’s about the community that we form through this sort of shared love and identity.”

Douglass-Knowles, who described himself as a “hip-hop baby” because he was born in Connecticut just weeks after DJ Kool Herc first created magic in the Bronx, has been using hip hop as a teaching tool for decades. Growing up in Norwich, Douglass-Knowles immersed himself in hip hop, thrilled every time he heard a new beat, saw a new video, or discovered a new artist.

“Just like—who are these cats and what are they doing?” he recalled. “And they look like me, and they talk like me, and they dress like me. When Run-DMC flipped the game—Grandmaster Flash and them, they was all dressing up like Bootsy Collins and so forth, Rick James style. And Run-DMC came through with the Adidas no shoelaces and … it became an anthem for me, growing up and so forth.”

His love for hip hop ultimately fed his interest in poetry, which led to an unexpected career in academia. Thursday, he took listeners back a few years to his courses at the Corrigan/Radgowski Correctional Center in Montville, where he was able to teach through a Second Chance Pell Grant. He had just performed his poem “HIP/HIV,” which ties tight bars with HIV and AIDS awareness, when he felt a thick, palpable sense of kinship in the room. By the time he finished, he could feel energy crackling through the space. He started a chant.

“When I tell you, we were just rocking,” he said. “You could just feel it resounding out the gymnasium and so forth. You could see the CO's getting nervous—they were nervous, one was on his radio and so forth—and I kind of took advantage of that and took it to another level. And it just felt really, really good. And it felt, it was bittersweet, because it was so hard to leave those brothers after. It was so difficult. And it always stood out to me. I always carry that with me. And if it wasn’t for hip hop, that moment would have never occurred.”

Sawyer, who was born on hip hop’s third birthday, recalled growing up in Harlem soaked in the sound. At the time, “we didn’t even know what it was,” but he knew there was something singular about it. Years later, the practical applications of hip hop became part of his work as a sociologist. The culture was his springboard for Hip Hop Heals, during which he worked with musician Clarens Descorias to use hip hop as a cultural bridge between Haitians and Dominicans. It’s also been an educational tool for him in New Haven, where much of his work happens outside of Quinnipiac’s quiet suburban campus.

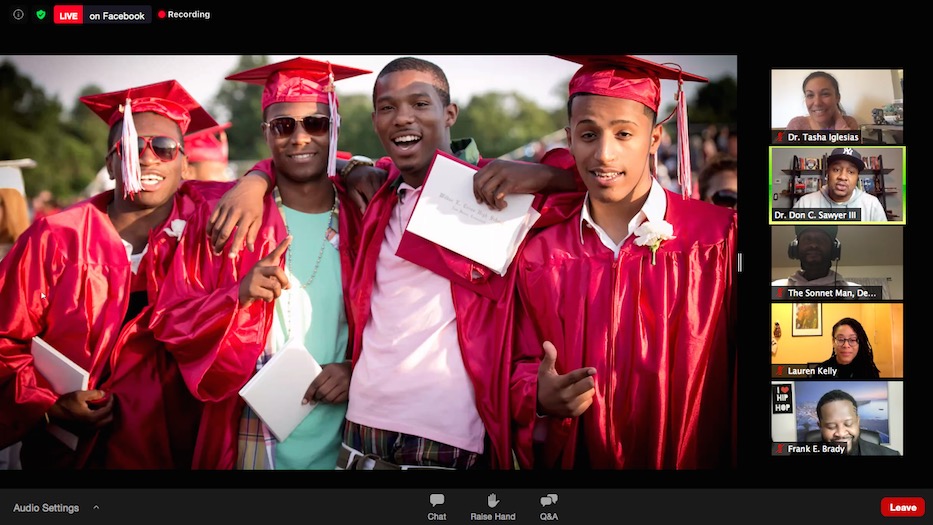

Thursday, he pulled up a photo of four teenagers, smiling and soaked in sunlight. He explained that the four had been part of an experimental two-year program at Wilbur Cross, during which he and Brady used hip hop as a sort of cultural intervention. The students “were seen as the school-skippers, the hall-walkers, and different things like that,” he said. Teachers and administrators looked to the program as a last resort.

The two “created this hip-hop space where students knew that they were seen, that they were heard, and that they mattered in that space,” he said. There wasn’t any extra-curricular tutoring as part of the program. The two never assigned extra work. Instead, they used the fundamentals of hip hop culture to nurture a group of young people who the school had effectively given up on. Every student who stayed in the program graduated from high school.

“That was a transformative moment for me,” he said. “Seeing them walk across the stage on that day. Some of the people who other people wrote off … that was important to me. And we did that through use of hip hop culture in that space. The culture that’s demonized by a lot of adults was the culture that reached those students.”

Glover, who writes for Flocabulary and Shakespeare Behind Bars in addition to his work as the Sonnet Man, reflected on a similar experience he had a few years ago. At the time, he was teaching a series of workshops at Title I schools in Detroit, Mich. At the beginning of the day, one of his students was quiet. Teachers had warned him beforehand that she might be withdrawn. Instead of prodding—“as a teacher, I don’t like to force the issue,” he said—he encouraged class members to write introductions about themselves.

When she offered to read, she received a standing ovation. Glover’s students “made her the star of the day,” he recalled. Before leaving the school, he invited her to perform alongside him in an all-school assembly. She’s now a spoken word artist at the University of Michigan, and still sends Glover excerpts of her work.

“As teachers, we’re all artists,” he said. “Every day that you do a lesson, that’s a script that you’re writing for your students to not only relay the message that you’re trying to leave for the end of the day, but it’s also a performance. Cause you gotta keep them interested. You gotta keep them locked in.”

A Language Of Possibility

The conversation doubled as a powerful reminder that hip hop is often overlooked or dismissed as unworthy of academic, literary, or musicological praise—in no small part because it clashes with the white supremacy that undergirds the ivory tower.

Kelly remembered teaching a class in a high school, and realizing that the administration didn’t fully support its existence after only nine of 1200 potential students registered for it. Glover said that he often gets schools that insist on seeing his work beforehand, because they’re concerned that it includes crude or sexual language. In actuality, Shakespeare’s original text is much more vulgar than the work he presents.

Douglass-Knowles recalled a colleague who had been promoted to department head, and advised him to create a curriculum around hip hop for his classes. When he did, she told him he couldn’t teach it in the department. He had to seek out the support of university leadership before the class was approved. He understood that she had made the offer halfheartedly, and didn’t consider hip hop part of the literary canon.

“I feel like there’s a lot of people out there who are missing the opportunity to bridge this cultural language, he said. “It’s been here for 40 years. We’re not going anywhere. And we’re not going to allow you to silence us. No matter how many times we fall, we’re gonna get back up.”

Iglesias agreed, suggesting that the biggest obstacle may come from academia and higher education itself. In her experience, it’s often her academic colleagues and supervisors who are most skeptical of the genre’s place in the academy and in the classroom.

“People that are not familiar with the culture have only been shown through the deficit lens,” she said. “So a lot of what our work is, and a lot of what we have to do sometimes, is help people unlearn. And reeducate them and share the culture.”

Brady added that he also sees misinformation coming from mainstream news and media outlets that depict hip hop as violent and intimately tied to crime. In his work, he tries to bust through those stereotypes and allow students to create organically. Sawyer nodded knowingly, his eyes wide underneath the broad brim of a Yankees cap.

“Sometimes our youth are looked at through the lens of deficits, as if it’s their own fault, right, for the reasons that they are marginalized and the experiences that they are having,” he said, noting the work of scholar Garrett Albert Duncan. “What hip hop helps us do is to see our students through the lens of possibility.”

He recalled speaking at Quinnipiac’s freshman orientation a few years ago, with an address built around Drake’s lyrics “started from the bottom, now we're here.” Nodding to Drake’s role as a poet and philosopher, he knitted it to students’ own journey to college and their charge for the next four years of their lives. Students got it, he remembered.

But when he came down from the stage, colleagues congratulated him as if he’d just given a performance instead of an academic address. Some of them congratulated him on “rapping,” rippling their shoulders as they spoke. His thoughts went to comedian Dave Chappelle, who once talked about hearing a laugh “that wasn’t laughing with him.”

“I was like, ‘I did not rap one bit while I was up there,’” he said. “I told a story to the students. And so sometimes when you do this work, I think people get so caught up in the delivery that it’s almost like they either forget or ignore that we have substance to the work that we are doing.”

Hip-Hop and Dismantling the School-to-Prison Pipeline (Hip Hop Studies and Activism)is available here.