Bregamos Community Theater | Elm Shakespeare Company | Fair Haven | Ice The Beef | Arts & Culture | Theater

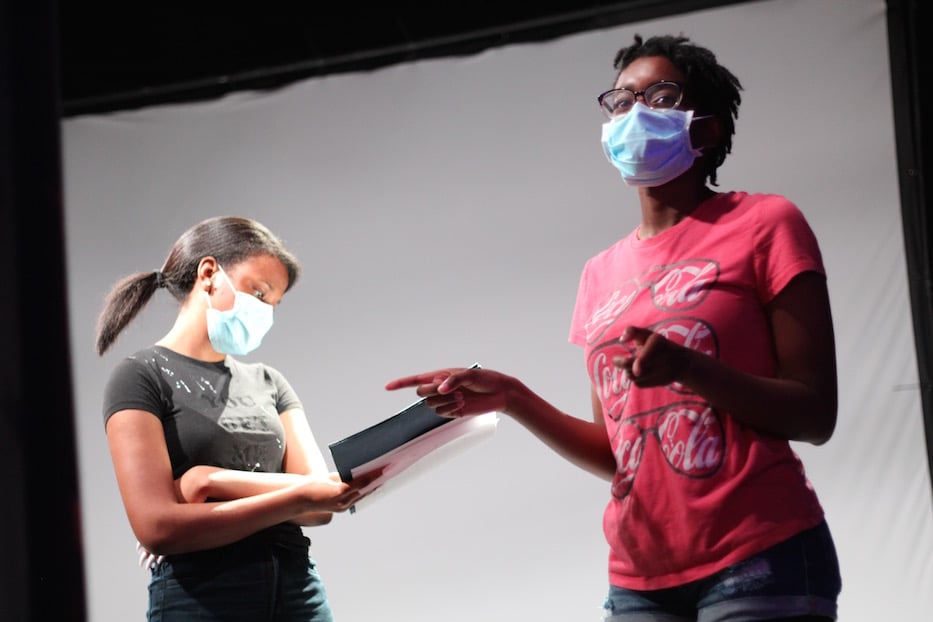

Manuel Camacho as Romeo and Zahra Hutchinson as Juliet. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Lady Capulet’s eyes widened and gleamed as she took in the scene around her. On the floor, her daughter Juliet leaned forward in a bright yellow sweatshirt, knees pulled to her chest. Her back was bent over them in a gentle C shape. She was trying to explain her love for Romeo, a guy with whom the family was at war—and to whom she happened to be married.

“Juliet, he killed your cousin!” Lady Capulet cried, rage blooming at the edge of her voice.

“He didn’t mean to,” Juliet responded, still shrinking into herself. “He just got mixed up in some stuff.”

That scene unfolded last Monday night, as Ice The Beef and Elm Shakespeare Company rehearsed an adapted, emergent Romeo and Juliet at Bregamos Community Theater. This year, the groups have joined forces to present an the play at the International Festival of Arts & Ideas.

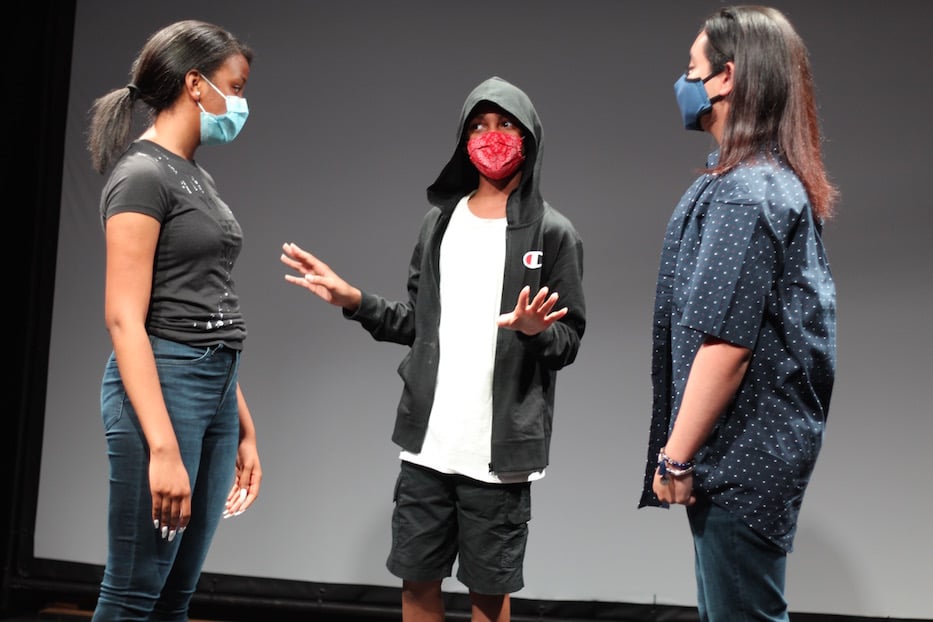

In addition to Shakespeare’s 1597 text, actors replay scenes with new, improvised dialogue and deescalation tactics, trying to prevent the murders of Mercutio (Catherine Wicks), Tybalt (Brian Starbird), Paris (Eliza Vargas) and untimely deaths and heartbreaks of Romeo (Manuel Camacho) and Juliet (Zahra Hutchinson).

The technique is from Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed, which places theater at the crosshairs of lived experience, present-day conflict and restorative justice. For actors, almost all of whom are in high school, the performance comes in a year that has seen a rise in citywide gun violence, including four homicides in under two weeks this May.

Sarah Bowles, education program manager at Elm Shakespeare and director of the show, said that the performance is meant to get audience members engaging critically with the material—and the conflicts that exist within their own lives. In addition to Bowles, actors are working with teaching artist Justin Pesce, a facilitator at Ice the Beef’s Waterbury chapter who also has a cameo as Lord Montague, and Ice The Beef Director Chaz Carmon. Carmon appears in the show as Prince Escalus.

“The point of Boal’s type of theater is that if we give the audience a different choice, then you are more likely to take that track in your own life,” Bowles said after a recent rehearsal. “They [the actors] really want to be able to do something to stop this violence, and by making art, they are doing something.”

The show hits hard in New Haven, she added. In the tragedy, two star-crossed lovers run up against a family beef that is so old no one can remember what sparked it or why they are fighting anymore. They may use swords instead of guns (Camacho does mime a pistol with his hand at one point) and bite their thumbs instead of trading verbal insults, but the blood that gets spilled is still human, and the loss of life just as heavy. Ultimately, the topography belongs as much to the city as it does to fair Verona.

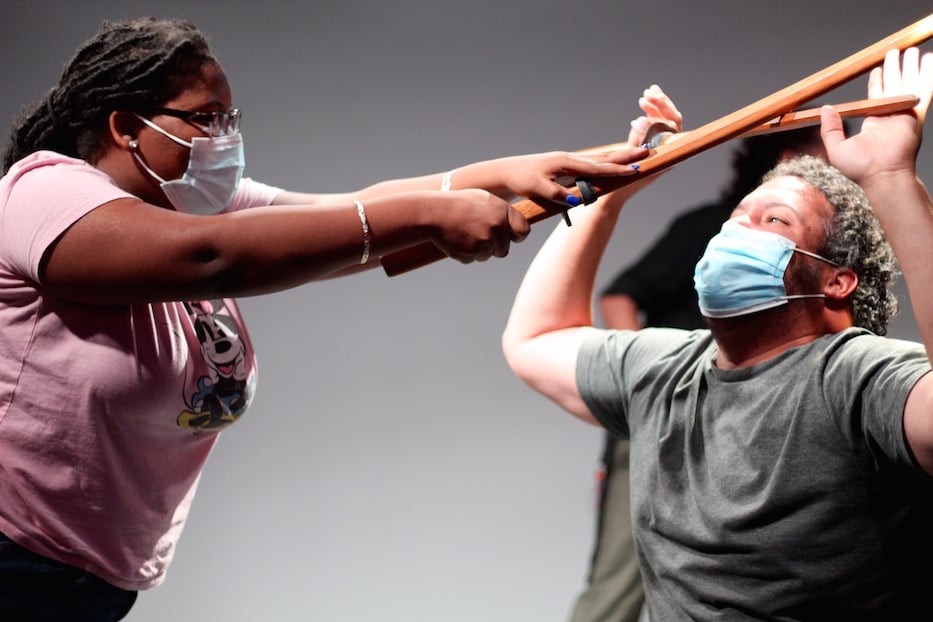

Allona Beard and Justin Pesce.

Part of Boal’s technique relies on improvisation and audience input, meaning that actors may not know what to expect on opening night. After practicing bows Monday, Antwain Johnson stepped up to the lip of the stage. In Shakespeare’s text, he plays Romeo’s kind and even-keeled cousin Benvolio, who tries to break up fights before they become irreconcilable. In real life, he is a member of Ice The Beef and a student at Notre Dame High School.

“That was the Shakespeare way, now it’s time to ice the beef,” he said, actors joining in on the last three words as if it were a rallying cry. “As you watch this, think of different ways characters could have iced the beef.”

Lady Capulet (Allona Beard) and Juliet took their places onstage. They looked out into the audience, and then at each other. What if Juliet had just told her mom that she didn’t want to marry Paris because she was in love with Romeo, Hutchinson asked.

Lady Capulet threw up her hands: did Juliet not understand the gravity of what Romeo had done in killing Tybalt? Juliet’s young cousin was dead. There was no going back.

Juliet pushed back. He hadn’t meant to, she told her mother. He was still reeling from the loss of his own cousin, Mercutio. It didn’t mean that he should spend his whole life paying for it. For a moment, the scene felt like it could have unfolded in a New Haven courtroom, families fractured on both sides of a loss.

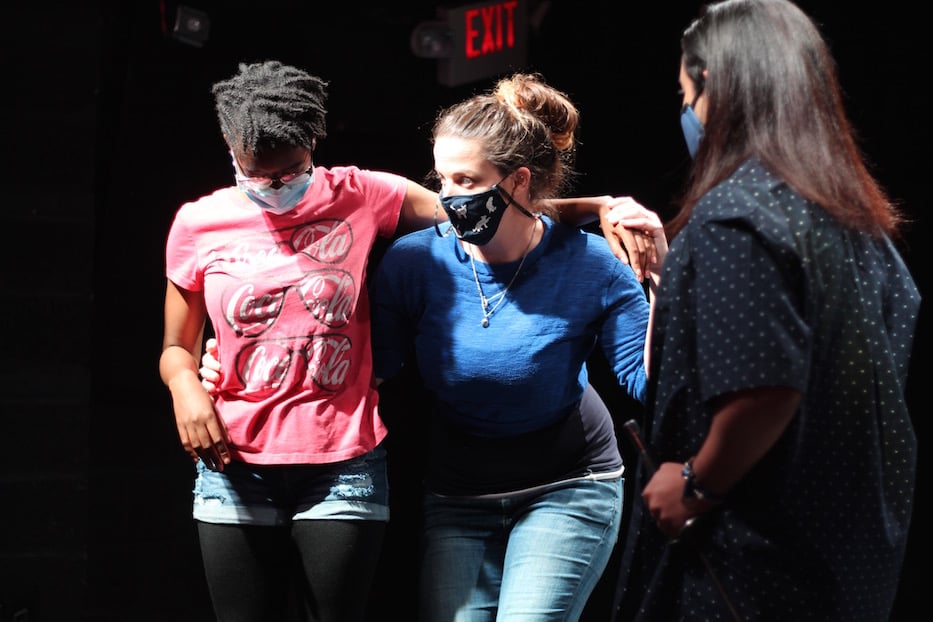

Inez Zackery.

Bowles turned around from where she was sitting on the floor. She looked at mom Inez Zackery, whose son James plays Friar Laurence and Peter.

“Do you think this would have worked?” she asked Zackery. After a pause, she added hastily, “We’re trying to brainstorm different opinions, so this is what it’s all about.”

Zackery shook her head. “I think the father would be feeling like he wanted to be part of the conversation,” she said. “Remember, the father does love his daughter.”

Wicks jumped in as an unexpected Lord Capulet. Bowles nodded. “And spell it out for the audience,” she reminded the actors. They took their places. Juliet started explaining her love for Romeo again.

“He killed your cousin!” Lady Capulet cried, nearly spitting through her mask.

“Someone was murdered,” added Lord Montague. “You’re married to a murderer.”

“Y’all don’t even know why you in it anymore!” exclaimed Lady Capulet. Juliet protested. Bowles called the scene.

“The great thing about our story is that it ends so badly that there’s nothing you can do to make it worse,” she said. “What you just did, creating a character who doesn’t even come out of our play, that’s an option.”

Bringing It Back To The Bard

In pulling the show into New Haven’s present, Carmon and Bowles have also made a series of artistic decisions that honor both Shakespeare and the young people taking on his words. No toy guns appear in the play, given the history of state-sanctioned violence on young Black kids playing with them in public parks.

In scenes where characters die, those actors remain standing onstage as spectral presences shrouded in white sheets. Monday, Bowles walked Wicks through Mercutio’s death. Wicks windmilled back. Bowles lifted her arms over one shoulder and brought her forward. She later said that the decision not only came from the visual of the sheets, but the understanding that bodies lying on stage may be traumatic to audience members who have experienced loss.

Actors have also conquered Shakespeare’s language, mining the Bard for his inherent humor and timelessness even in the midst of tragedy. Monday, actors ran through the second act, pulling back the curtain on what infighting, what insults, what familial misunderstanding might have been undone before it left six people dead in its wake. Camacho, who had never acted before landing Romeo, held tight to the florid, over-the-top language that Shakespeare gave his lovesick character to work with.

At the top of rehearsal, he wove through the half-lit theater, his hands wrapping around the pillars that stand in the space. He sprang forward at the first glance of Hutchinson, who floated onto the stage in jeans and a yellow sweatshirt. He gave a shuddering breath, so loud that Bowles laughed through her embroidered mask.

“She speaks!” he cried. “Oh, speak again, bright angel. You are as glorious as an angel tonight.”

The imaginary topiaries rustled with his presence, and Hutchinson startled a little onstage. Light fell softly over her face, making her sweatshirt turn the color of butter and daffodils. At the sight of Romeo, she flinched noticeably, and then softened. Bowles raised her hands.

“Zahra, it’s okay to scream!” she said. “If you’re on your porch outside and someone jumps out of your bushes, you’re going to scream.”

In another scene, actors walked through the sword fights that ultimately lead to the deaths of Tybalt and Mercutio. On stage, Wicks and Starbird faced each other, swords glinting. They lunged and then stepped back. Fully Romeo and fully himself, Camacho held Mercutio’s hands in the air, so that they could not come down and end Tybalt’s life. Tybalt—who had never learned deescalation tactics—took it as a chance to strike.

“I am hurt,” Mercutio said, voice breaking as Wicks doubled at the waist.

Wicks and Bowles work through Mercutio's death.

After rehearsal, students said that the work feels present centuries after it was first written. Hutchinson, now a sophomore at Engineering and Science University Magnet School (ESUMS), has acted with Elm Shakespeare since discovering the group in middle school. She jumped onboard as Juliet just weeks ago and is almost completely off book.

“With all the gun violence and Black Lives Matter and all the hate against minorities, I can see how there could be ways to just deescalate situations, and I think it’s great that Ice The Beef is doing that,” she said.

Beard said she jumped at the opportunity to audition last year, after Carmon called the house and described the project. A freshman at Amistad Academy, Beard has found the last year exhausting and “kind of boring, if I’m going to be honest.” When she landed the role of Lady Capulet, she could feel her mood lifting. She started to rehearse with the group virtually, and then joined them for in-person rehearsals in February.

“I was super excited,” she said. “And I’ve been here ever since.”

Camacho added that he can’t think of a better artistic response to the amount of violence the city has seen this year. When he isn’t running his lines, he serves as the Latino Caucus President for Ice the Beef and a member of New Haven Rising’s youth leadership team.

“We thought: the time is now,” he said. “Right? We’re in a pandemic. People are stressed. Tensions are high everywhere—across the nation, across the city. We can provide some relief to the city. Doing a play, making sure that we’re providing our energy into it, but making sure that we also spread the message of love, of peace, deescalation, because that is who we are.”

The work will premiere June 26 on the New Haven Green, and take place again during Elm Shakespeare's first-ever outdoor youth theater festival in August. Find out more here and here.