International Festival of Arts & Ideas | Arts & Culture | COVID-19

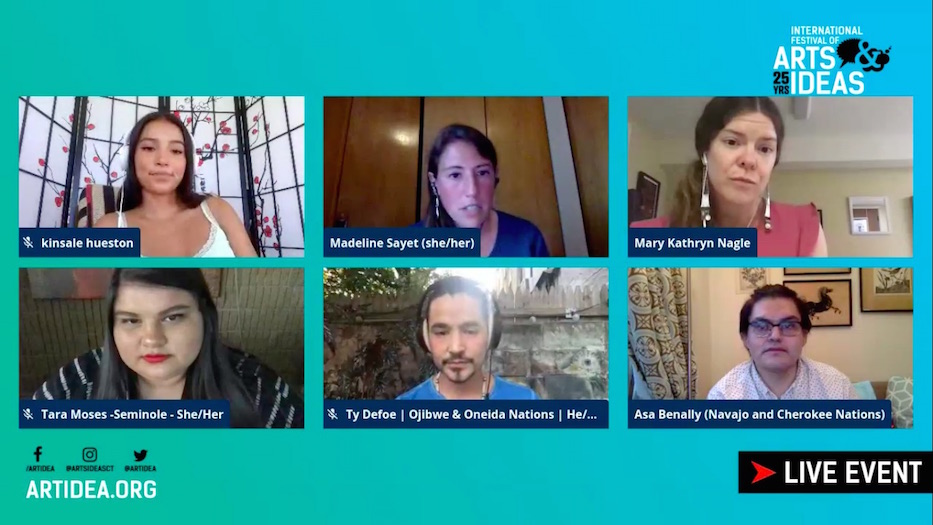

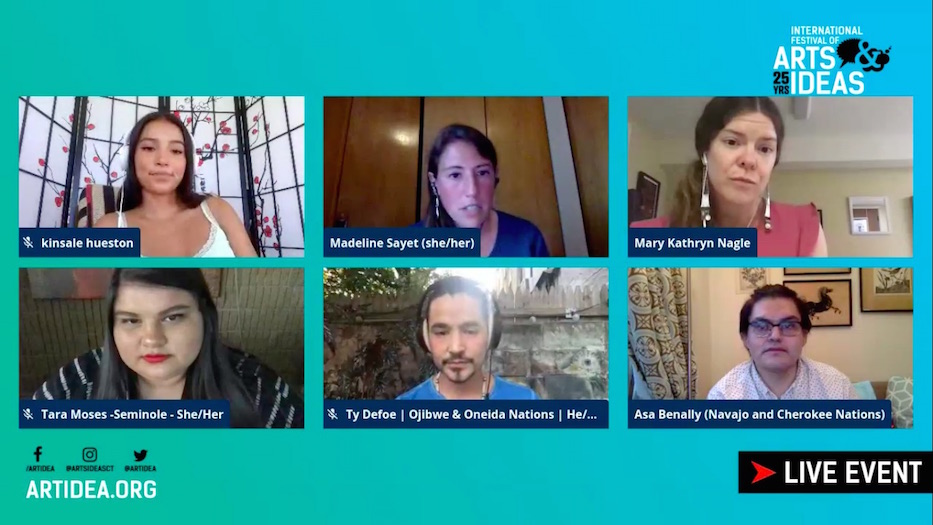

| Facebook Live/International Festival of Arts & Ideas Screenshot. |

To tell Native stories onstage may be a starting point, but it’s not enough. It never was. There must also be room for joy, humor, magic, and dispatches from the future that are not always tied to the trauma of the past.

That was the consensus Tuesday night, as six Native artists gathered virtually for “Stories, Sovereignty, and Imagining Forward” on YouTube, Vimeo and Facebook Live. The panel was part of this year’s 25th annual the International Festival of Arts & Ideas, which has gone completely online in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The conversation was moderated by Madeline Sayet, a director, playwright and performer who is also the executive director of the Yale Indigenous Performing Arts Program (YIPAP) and a member of the Mohegan Nation. Panelists included director and playwright Tara Moses, costume designer Asa Benally, activist, writer, and multimedia performance artist Ty Defoe, lawyer and playwright Mary Kathryn Nagle, and poet and performer Kinsale Hueston.

All of the panelists are Native: Moses is a citizen of Seminole Nation of Oklahoma; Benally grew up on a Navajo Reservation in northern Arizona and is also half Cherokee; Defoe is Ojibwe and Oneida; Hueston is a member of the Navajo nation and centers Diné storytelling in her work; and Nagle is a citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. She was the inaugural director of YIPAP and returned to New Haven earlier this year to present Manahatta at the Yale Repertory Theatre, on which Defoe served as the movement director.

“As Native theater artists, we’re too often separated from each other, or set apart, or forced to represent, or be studied, or educate,” Sayet said at the top of the discussion. “Rarely are we given permission to just be ourselves, in relaxed and honest deep conversation.”

Part of the problem, artists suggested, is a structure of American theater built on white supremacy. Both Defoe and Sayet described a series of boxes into which they are often pushed, from theaters that assume—incorrectly—that all sovereign nations have the same traditions to those that will accept a work by a Native playwright, and then fill a show with white and non-Native cast and crew members.

Nagle recalled her own shock years ago, when she transferred from law to theater and assumed the latter world would be more enlightened than the former. During law school, she had spent years reading nineteenth-century court proceedings that defined Native people as “racially inferior savages and heathens.” Many of those cases, which have not yet been overturned, use language that still determines legal outcomes today.

“When I went to theater after having my legal background, I kind of thought a lot of people in the theater are very liberal, very progressive,” she said. “I thought, they’re not gonna be down with that. They’re not gonna be cool with that, right? We can’t live in a country where the Supreme Court says we’re racially inferior because we don’t worship Christ. That’s ludicrous, right? No one’s gonna buy into that.”

She was wrong, she told viewers. For five years, she watched as hundreds of mainstream theaters in New York City passed over the work of Native playwrights and directors. She watched as performers donned redface, and her own life story became caricature.

“We were ridiculed and dehumanized onstage, and it was kind of heartbreaking, because I held the theater in a higher regard,” she said. “It just was heartbreaking.”

Moses, who now runs the Indigenous and Latinx-focused Binge Theatre Company and Groundwater Arts, had a similar experience for the first two decades of her life. She recalled growing up in a world where Native playwrights simply weren’t discussed. As a kid, her first role was an orphan in Oliver: The Musical. From there, she “learned to adapt,” working around the fact that she was a non-white body in a largely white dramatic world, with colonial conventions of time, space, actors and playwrights.

By the time she reached college, she had not read, seen, or acted in a single work of Native theater. She asked teachers where she could find other Native playwrights, and repeatedly watched as they shrugged and insisted they didn't know. It was only on a trip to the basement of the campus library—"very telling, because it was the basement,” she joked—that she found an anthology of work by the living Native playwright William Yellow Robe.

She started Googling Native playwrights, watching as names filled the screen. There were writers who she now considers both heroes and colleagues, like Suzan Harjo, Dr. Twyla Baker, and Larissa Fasthorse.

“I was sitting here, and I was like: Why was I not taught about these?” she scrunched her eyebrows as she spoke. “We know why. That’s not the real question. But, that really got me thinking.”

But it doesn’t have to be that way, she continued. Since that first Google search, Moses has used Native storytelling to make a kind of theater that centers healing, comedy, climate justice, and both Native and Latinx voices. Her colleagues have made that push in their work too.

“When I think about the stage and I think about the sovereignty of our stories, I think about our right as Native people, regardless of what tribe we’re from, all of us, the right to share our stories instead of having a non-Native share them for us,” Nagle said. “Because that has been the history of the American theater. Right? Where our own sovereignty over our own stories has been erased and replaced.”

One by one, panelists outlined a vision of theater that centers Native voices both onstage and off, in which artists and makers are no longer beholden to the desires of white bodies in white seats at white-led institutions. The push forward joins a wider movement to center Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) voices in American theater, and to move away from a colonialist, white supremacist narrative that has dominated stages for hundreds of years.

“There’s been this historical tendency by the American theater to present, as it’s been described, Native theater as monolithic,” Sayet said. “In fact, we know there’s more than 563 federally recognized tribes, which means that actually the practicing of that sovereignty is different in every experience.”

Hueston, a Yale student who now leads the changing womxn collective, described a model in which that’s already a possibility. As a kid, she was raised in the Los Angeles Urban Indian Arts community, which included acting in Nagle’s plays. Out of acting, she began to write poetry as a way to balance and navigate the worlds she inhabited—her reservation community, her Urban Indian Arts community, and the majority-white neighborhood in which she lived and went to school.

On one hand, she had a model to work from. On the other, she turned to popular media, and never saw herself represented in any of the sitcoms she watched or novels she read. She shouted out a second wave of Native Renaissance authors to whom she was able to look for inspiration—but wanted to see more of it in the mainstream. She said that she’s been having dreams about an all-Native Marvel movie, where characters have superpowers.

“I learned to provide tools to underrepresented communities to tell stories on their own terms,” she said. “Not the colonial way of stories. You could mess with time. You could mess with the typical way of doing research and archival work. And it didn’t have to be the typical white way of telling stories to be true.”

Benally, who considers costume design a form of deep, rich storytelling, noted his need to both honor and recognize the past while decolonizing it for audiences—and for the future of the craft. He reminded listeners that theater, as it is widely understood, began as part of religious ceremonies.

“Looking back on the past, figuring out something in the present, and trying to figure out solutions to have, like, a good future,” he said. “So I think there is this whole aspect of exploring the emotional and exploring the trauma on the stage and the rehearsal room together that can make the art stronger for the future.”

Moses chimed in, noting the importance of also making room for joy. She called on theaters to support work that transcends trauma, and makes space for the healing, humor, and depth that has always been part of Native storytelling. She described the field of epigenetics, in which research suggests that inherited trauma is not just a psychological state—it is a biological and genetic one too.

“How do we heal from that?” she asked. “That is mass community trauma. To heal from it, it’s mass, community-led healing. That’s my theory on it. And so when I’m thinking about the stories I want to see moving forward, I want to see those healing stories. I want to see those cathartic stories. I would love to watch a really rom-com Native show that’s just so silly, and we don’t talk about colonization and our struggles and all that jazz. It’s just something so silly, about who is snagging who, right?”

“There is plenty of space,” she added. “We are well-rounded, complex human beings to tell frivolous stories. I would love to see a frivolous musical that is just a bunch of Natives on stage dancing around, not to educate or advocate.”

Sayet, laughing as she spoke, jumped in. She recalled the number of times she had proposed a “happy, Native coming-of-age musical” to arts organizations and been instantly rebuffed. Each time, they insisted that there wouldn’t be interest in that show. Instead, she had shared numerous stages with other Native actors, perplexed and then aghast when her colleagues were asked to “sing that one Indian song” by white people in the room.

Jumping in, Defoe seized on the importance of humor. He described a humor that non-Native audiences often miss, because the works they are seeing focus almost exclusively on loss and trauma or are processed through a white lens.

He also introduced listeners to the idea of Indigenous Futurism, in which time is no longer defined on a white, Western, colonialist clock and characters are not bound to their present. The movement pushes back against the idea of settler futurity, in which white people are still unwilling to abdicate their privilege, which is in turn an inheritance of violence.

“Yes, it’s healing from history’s past, but it’s also thinking about the future,” he said of a current piece that he is working in. “I have a tendency to lean more towards that, because they’re like: What? Technology and Native people? Those two things don’t go together. I’m like: Why can’t grandma be sitting in her wigwam with her iPad, because it happens in real life. It needs to happen in stories.”

“I think futurism is kind of discounted by people, because they’re like, ‘well, it’s all dreaming and envisioning and not acting,” Hueston chimed in. “But actually, Indigenous Futurism is a set of practices in the present that we exercise and we do, to help us bring the vision of collective liberation and bring what we want closer to us and get us there. It’s an active envisioning.”

In real life, Moses has already used that framework as a way to decolonize her work: she gives actors more time away from rehearsal and performance spaces, despite industry conventions that demand working through weekends, often on grueling schedules. If she had a superpower, she told the group, it would be to control time.

“Just like, pause it, because we need a nap,” she said. “Or like, pause it because we’re doing some good stuff. Again, that’s in opposition to the colonial concept of time.”

“When I hear that question, I just think of the word possibilities,” Benally chimed in. “Just kind of like, endless possibilities.”

To find out more about the International Festival of Arts & Ideas visit its website.