Culture & Community | Dixwell | Politics | Newhallville | Justin Elicker

Lucy Gellman Photos.

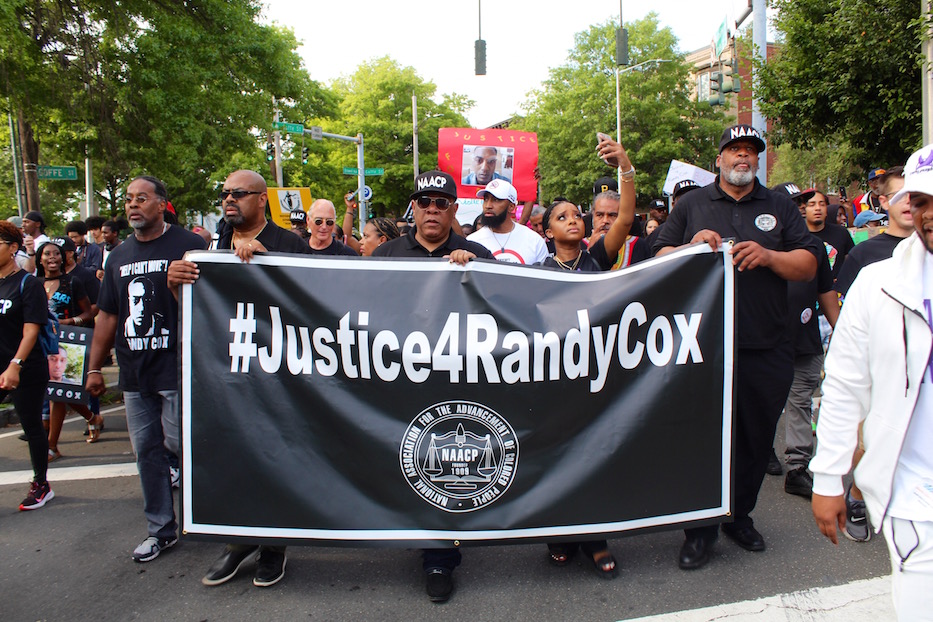

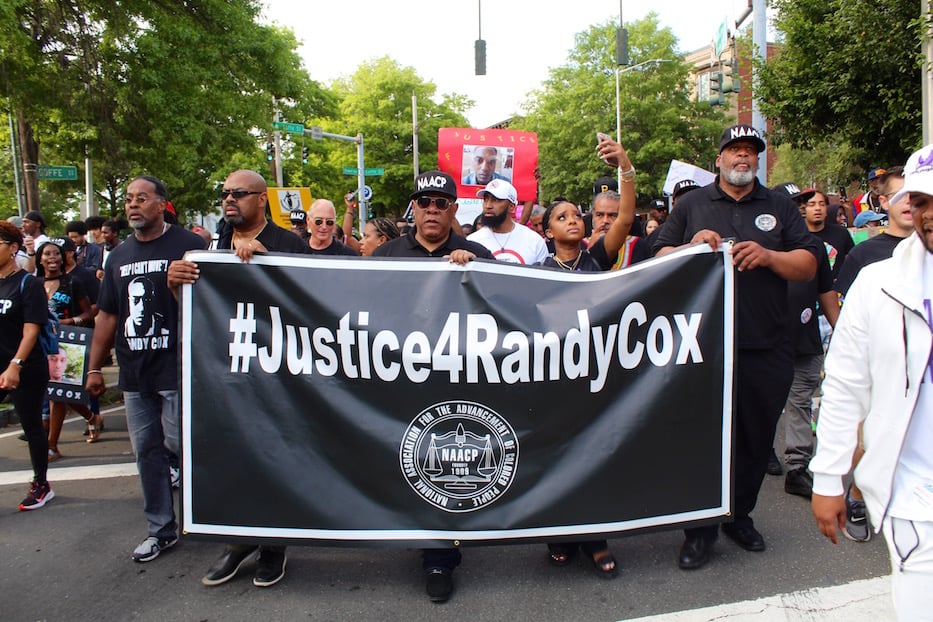

The NAACP and ACLU marched alongside Black Lives Matter New Haven. Ice The Beef moved in lockstep with the New Haven Peace Commission and Hamden Action Now. Fathers Cry Too found its footing alongside state legislators as the New Era Young Lords made sure no one was left behind. Randy Cox’s friends, family and neighbors kept each other going.

And until Doreen Coleman’s knees couldn’t make it one more step, attorney Ben Crump held her hand, and listened as she cried for her son.

Amid cries of “How do you spell guilty? N-H-P-D!” “Say his name! Randy Cox!” and “If I say my neck is broke/Don’t take it as a joke!” 500 New Haveners gathered Friday outside the Stetson Branch Library on Dixwell Avenue to demand justice for Richard “Randy” Cox, who on June 19 was arrested on Lilac Street, thrown across a seatbelt-less-police transport van during an abrupt stop, severely injured, and dragged into a cell while in New Haven Police Department (NHPD) custody.

The march was organized by the Greater New Haven NAACP, with support from Stetson Branch Manager Diane Brown and several state and municipal officials and anti-violence groups in the city. Brown, who has known Cox’s mother through the library for years, said she was happy to offer up the space.

After congregating at Stetson, the crowd marched the nearly two miles to 1 Union Ave., where the NHPD’s brutalist, fortress-like headquarters rises from the street. The city arranged for school bus transportation to ferry people back to Stetson after the march—seemingly a first in years of citywide marches against police brutality.

Cox is now intubated and paralyzed from the chest down at Yale New Haven Hospital, where he is receiving treatment for his injuries. Since that night—on which Black people across New Haven were supposed to be celebrating the freedom of Juneteenth—five NHPD officers have been placed on administrative leave. Crump, recognized nationally for his coverage of high-profile police brutality cases, has stepped onto the case alongside Connecticut co-counsels Jack O’Donnell, Lou Rubano, and R.J. Weber.

Latoya Boomer and Jack O'Donnell taking to Cox as they march.

“It’s hard,” said Cox’ sister, Latoya Boomer, who held a phone for the entire march so her brother could watch from his hospital bed. “Used to seeing him walking around, a lot of people know him from the neighborhood, always around, smiling, happy. And then to see him in a hospital bed, where he can just nod his head yes or no.”

As hundreds gathered outside the Stetson Branch at 197 Dixwell Ave., something different took shape: a joining together of legacy organizations and fiery, grassroots groups that are often some of the first and the most vocal on the front lines. In the past three years, those two worlds have often been at odds in not whether but how they object to state-sanctioned violence against Black people.

The first—groups like the NAACP—have called for reform, the second for abolition. The first has held panels and discussions, the second has taken to the streets with teach-ins and marches that take over the highway and sometimes last for hours. Groups like the Outraged Elders (there in full force Friday) have often occupied a space in between.

Friday, they came together with a common goal, filling the streets with loud, full-lunged protest chants as they criss-crossed neighborhoods and called for both greater police accountability and a federal investigation into the case. From a hospital bed, Cox watched much of the march with tears streaming down his face.

When they dispersed to Public Enemy’s “Fight The Power” hours later at 1 Union Ave., the question hung in the air: was there new momentum around this coalition building? Or was it a single, fleeting moment?

Around the library, dozens began to trickle in just after 4 p.m., where a tent from the Greater New Haven NAACP was already set up. T-shirts and baseball caps that read “I Can’t Breathe,” “Justice for Randy Cox,” and “#NAACP” dotted the space. Dori Dumas, president of the organization, buzzed through the growing crowd in a pink polo emblazoned with the NAACP logo, greeting friends and colleagues every so often. For the past weeks, she has helped organize a series of community discussions, including an hours-long talk with Crump and members of Cox’s family at the Stetson Branch.

Stopping for a moment by the NAACP’s bustling tent, Dumas said she hoped to see not just more measures toward police accountability on a municipal level, but also a federal investigation into the case. A longtime advocate for justice in the city, Dumas pointed to Cox’s injuries as symptomatic of a larger, disconcerting and system-wide violence in the New Haven Police Department and policing more broadly.

“It’s bigger than Randy,” she said. “This is bigger than his family. We’re lifting them up in prayer. We are speaking out about justice. We’re gonna be coming out in big numbers.”

Newhallville Alder Devin Avshalom-Smith, whose ward includes Lilac Street, said that he hopes to see greater police accountability not only around the officers who harmed Cox, but in the department. For him, the single incident is reflective of a larger problem present in the department. He said he is cautiously optimistic about Chief Karl Jacobsen, who was sworn in this week and has vowed to deepen the department’s commitment in community policing.

“It’s beyond concerning,” he said. “It’s scary, it’s disheartening, and unfortunately I think it speaks to a larger culture about the way people in my neighborhood are treated generally. I think this opens up a larger discussion about the fact that we need more resources and investment from this city going into Ward 20. It’s unconscionable that we don’t have the basic staples of many other communities.”

In particular, he said, he wants to see a significant and sustained reallocation of resources to his neighborhood—where residents don’t have a fresh food market, youth center, or park that other neighborhoods have in multiples.

A few feet away on the curb stood members of Black Lives Matter New Haven and Citywide Youth Coalition—both groups that are often at the forefront of marches, and have helmed dozens of mutual aid efforts in the city. Ala Ochumare, a founding member of BLMNHV who grew up in Newhallville, called the case “another wake up call for folks” rather than an isolated incident. As she spoke, she noticed the new faces in the crowd.

“It’s the same shit over and over again,” said Sun Queen, a fellow founding member of BLMNHV who grew up with Cox’ sisters in Newhallville, and moved out of the neighborhood because the reminder of her own brother’s death was too raw. “We are actively dying. And now again, we’re fighting for our lives.”

Mellody Massaquoi, an SCSU student and longtime member of Citywide Youth Coalition who grew up in Newhallville, described herself as “angry, but not surprised.”

Attendees continued to trickle in, many with handmade signs calling for justice for Cox, and posters that listed the sheer number of Black people killed and injured at the hands of police. A lifelong Fair Havener who is now Youth President of Ice The Beef, Manuel “Manny” Camacho made his way through the growing crowd, greeting state legislators, organizers, and members of the New Haven Peace Commission.

As a rising senior at James Hillhouse High School and a Latino youth in the city, Camacho had been able to keep it together until he watched the videos of police—cops he recognized, he said—dragging an injured Cox from the transport van into a cell. As they had, Cox had repeatedly told them that he could not move and repeated the phrase “I think I broke my neck.”

Camacho thought that he was going to throw up, he said. He had seen incidents of police brutality before, including in his own city. But there was part of him, he said, that still wanted to believe in the police as a group entrusted with the protection of a community.

“It’s hard not to feel infuriated, but it’s also hard not to feel betrayed,” he said.

He added that he hopes any citywide organizing from the case—particularly from groups that are loud on policy, but do not always show up to march—will continue far beyond the next weeks and months.

Blasting Beyoncé’s “Love On Top” over the block, Earl Cable—or DJ Self-Made, as he prefers to be recognized when he’s behind the turntables—also called for greater police accountability. For him, that means that “I wanna see these cops be held accountable,” he said.

On Friday, he was doing his part by setting the soundtrack, getting marchers ready with a constant stream of sound. When they set out on Dixwell Avenue, he said his charge was to pack up as quickly as possible and head to 1 Union Ave., where music would greet them as they arrived at the station.

Born and raised in New Haven, he recognized what happened to Cox as “nothing new,” in particular the rough ride that Cox received after he was arrested on Lilac Street. For him, the case feels personal: he’s a New Havener, a Black man, and a dad of five. When he got the call asking if he’d come, he said he was more than happy to show up.

“I do this from the heart,” he said. “This is meaningful to me. This could have been me. It could have been my sons.”

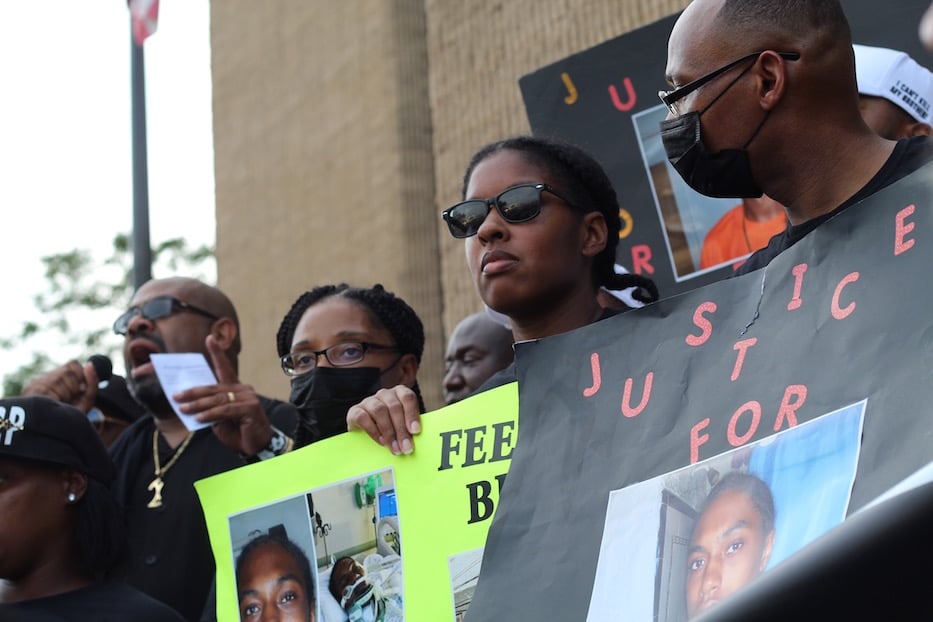

Many of Cox’ friends and family members also flocked to Stetson. Sitting on the grass, Cox’ nephew Cortez Legrant and his sister Jaelyn Roberts prepared to head to 1 Union Ave. with a sign that read “I can’t move. Justice for Randy.” Legrant, who lives in Wisconsin and traveled to New Haven for the march, said he wants to see more police accountability, “so that something like this wouldn’t happen again.”

Like his uncle, Legrant knows some cops may see his Blackness and his maleness before they see his humanity, he said. He called the police violence that his uncle sustained “crazy” and an upsetting abuse of power. “It’s not supposed to be like that anymore,” he said.

"I want to see accountability, lots and lots of accountability,” chimed in Roberts, who is a doula and grew up in New Haven. As someone who lives in the city, she’s not just close with Cox—she’s invested in the wellbeing of his siblings, and hers.

“Really, how I feel is hurt, especially for my siblings,” she said. “This is something where I love them so much, but I just don’t know what I can do to change the situation, what I can do to fill the void inside of them that they feel inside.”

At the corner of Dixwell Avenue and Foote Street, Emanuel Martin stood with 13-year-old James Swan, posing with a homemade sign. On it, Cox’s face beamed out, full of life. James, who called Cox a mentor, had come back from a trip to Rhode Island when he heard the news that Cox had been severely injured by police.

He said it felt natural to return to New Haven for the march; Cox has done so much to nurture him. “He’s just a cool person to talk to,” he said. “Lots of positive vibes. He looked out for me.”

Martin, who grew up in West Virginia and moved to New Haven four years ago, saw Cox in the neighborhood almost every day, he said. Around him, Cox was a sweet friend, always ready with a joke. If there was a cookout, he was the one who always made sure that neighbors were invited, and that there was extra food for them to eat. He was on Lilac Street the night Cox was arrested, and remembered watching him at the grill in the moments, laughing and joking with neighbors.

“When I watch the video, my heart hurts,” he said. “I think the cops should go to jail.”

Before Pastor John Lewis sent marchers off with a benediction, members of Fathers Cry Too wove through the crowd, handing out cards with the organization’s mission and contact information. Thomas Daniels, who co-founded the organization with Charles Clark in 2009, said he saw Cox’s life-altering injuries as “nothing new,” a throwback to the “beat-down posse” that terrorized Black and Brown New Haveners in the 1980s, and has persisted through today.

As he sees it, he said, community policing died when Chief Nick Pastore left the department in 1997.

“Thank God for cameras and cell phones,” he said. “We need accountability. It’s about time. It’s long overdue. The police have been getting away with it without being held accountable.”

That momentum carried into the streets, as marchers carried a long black vinyl banner that read #Justice4RandyCox and began to move forward, their voices lifted toward the sky. As they walked down Dixwell’s wide berth, marchers seemed to multiply, reaching back several blocks. Toward the back, the Black Lives Matter and Pan-African Puerto Rican flags flapped in the wind from where the New Era Young Lords were marching.

“When I say my neck is broke?!” Crump cried.

“Don’t take it as a joke!” the crowd cried back.

“No justice!” Tamika Mallory cried.

“No peace!” the crowd bellowed back.

“If we don’t get it?”

“Shut it down!”

On Broadway Avenue, Crump lifted a single hand to the sky, where white, wispy clouds hung low across an expanse of light blue. He explained to the crowd that they needed to stop for a moment, so Coleman could catch her breath and give her knees a minute to rest. Within seconds, people were fanning her with their bright, hand-decorated posterboards. The chants transformed from “Say his name!” to “We got you! We got you!”

“You all are never gonna be alone, Ms. Doreen,” he said. “Never gonna be alone. You all got our backs. As lawyers, Mike Jefferon, Jack O’Donnell, Louis, R.J. [Weber]. We the lawyers in the courtroom. But you, y’all, y’all the lawyers in the pubic. And we can’t do it without y’all.”

Activist Tamika Mallory stepped forward, decrying the police treatment of Cox as both inhumane and symptomatic of a much larger, national abuse of power. She tied the case to the state-sanctioned murders of Breonna Taylor, Freddy Gray, Ta'Neasha Chappell and most recently Jayland Walker. Last weekend, Walker was shot over 60 times for fleeing a minor traffic stop in Akron, Ohio.

“We are dying all over this nation,” she said. “Don’t let anybody tell you it’s isolated. It is not. It is coordinated. They’ve been killin us, they continue to kill us. And only we are responsible for fighting the power and making sure they are never comfortable. They must never be comfortable. Every time one of us falls, all of us must stand.”

As the march lurched back to life, it flowed from Broadway Avenue up Em Street, turning onto state in one large knot of chanting bodies. At the front, strollers found their way alongside organizers from Black Lives Matter New Haven and Hamden Action Now. Closer to the back, marchers who needed a little more time took it in stride. When they reached the underpass on Union Avenue, their cries of “Randy Cox’s life matters” and “Ain’t no power like the power of the people ‘cause the power of the people don’t stop” grew to an echoing roar.

It carried through to the police station, where Crump, Mallory, Attorney Michael Jefferson and members of the Greater New Haven NAACP and Cox’s family assembled on the steps, an oversized sign for the NHPD looming in the background. As people filled Union Avenue, Mallory took the mic and lambasted the behavior of not just police in New Haven, but police across the country, whose abuses of power reach back to the founding of policing in America.

Her voice sailing across the crowd, she teased at the difference between “peaceful”—a word that law enforcement and members of the media alike often use when describing how protesters should act—and “nonviolent.” Attendees sent up a roaring cheer as she spoke.

“We are nonviolent, but we are not peaceful, and we are not calm,” she said. “We are angry, and we will continue to shut the streets down until we get justice. Be nonviolent, because they want you to throw a brick. They want you to burn something down so that the media can shift the narrative to the hoodlums and the thugs in the street.

“But instead, we organize, brothers and sisters, we show who the real thugs are,” she continued. “The thugs are the sergeants and the captains and the police officers who did not do what was right for Randy Cox and for our brothers and sisters all over the land.”

Jefferson, a longtime champion of civil rights in New Haven and the head attorney for the Connecticut NAACP, noted how differently Black people are policed than their white counterparts across the country. He looked to the case of Waker, who had 60 bullets fired into his body in Akron, Ohio after a traffic violation.

Just days later, the white Highland Park shooter, Robert Crimo III, was arrested without incident after killing seven and injuring over a dozen others at a Fourth of July Parade in Illinois. A 49-year-old man in Kentucky, also white, was taken into police custody without incident after killing three officers and a police canine unit.

That extends to New Haven, he said. He criticized Mayor Justin Elicker for tapping Renee Dominguez, against whom the community openly and repeatedly spoke out, for police chief. Dominguez served as acting chief until earlier this year, despite a vote against her appointment from the New Haven Board of Alders.

“There is a collective contempt, in my mind, for Black life in this country,” he said. “Merely for existing. Ask yourselves: What have we done to them? What have we done but built this country? What have we done but given our blood, sweat and tears in every war for this country? Why are we hated so much?”

After traveling from Florida, Cox’s brother Jerry “Jeff” Brown got the crowd cheering, responding and applauding as he lambasted the city for announcing new policies instead of enacting immediate, severe and long lasting reforms that would hold the five officers who injured his brother—and many officers to come—responsible for their misconduct.

He started quietly, his voice rising to a trembling crescendo as he recalled visiting with Randy in the hospital earlier on Friday. A nurse for 22 years “it’s different when it hits your house,” he said. When he saw his brother lying in the hospital bed, he urged him to keep fighting, promising that “We gonna fight out there. We got this.”

“We don’t want no more rules! We don’t want no more procedures,” he said. “We don’t want no more of your politics! What we want is some goddamn accountability.”

"It’s time for some goddamn consequences!” he cried to calls of “you better preach!” “Because if it don’t change, it’s gonna be your family next. It’s gonna be your brother next if it don’t change. I will not be silent until you change your behavior. We are tired of it. We are sick of it. And it’s time to get this house in order!”

Watch more from the march in the videos above.