Culture & Community | Goffe Street Armory | Architecture | Arts & Culture | Artspace New Haven | Whalley/Edgewood/Beaver Hills

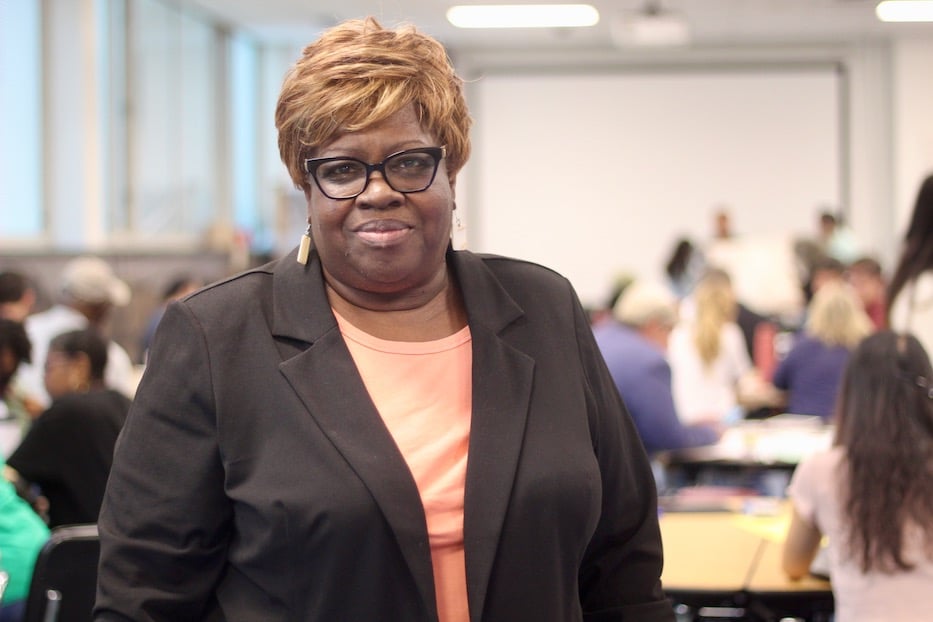

Top: Chris Wegren, Charlotte Leib, Salwa Abdusabur, Arden Santana and Hafeeza Turé. Bottom: Rev. Lucille Brown. Lucy Gellman Photos.

When Rev. Lucille Brown drives past the Goffe Street Armory, she can already envision a hub for arts education, where New Haven’s youth have a safe place to go after school and on the weekends. If she closes her eyes, she can see a stage, and imagine music flowing through the building.

But when she pulls herself back to the present—a great shell of a building, standing quiet as a tomb—she often asks herself the same question. “What are they doing with it?!”

Wednesday night, Brown brought that question to the second Goffe Street Armory Public Meeting, held in the sauna-like cafeteria at James Hillhouse High School. For over two hours, the meeting doubled as a chance to get updates on the building—including potential state funding—and hear from New Haveners about what they’d like to see for its future uses.

It follows a Goffe Street Armory meeting in May with almost exactly the same format, discussion, and concluding ideas. Like that event, over 100 attended, nibbling on hummus, falafel, biryani and baklava from Havenly Treats as they discussed what they hoped to see. The 155,000 square foot building currently sits empty at 290 Goffe St. across from DeGale Field on one side and the New Haven Correctional Center on the other.

Together attendees included neighbors, city officials, small business owners, nonprofit leaders, lifelong New Haveners and members of the Armory Community Advisory Committee (ACAC), all drawn in by the building’s uncertain future.

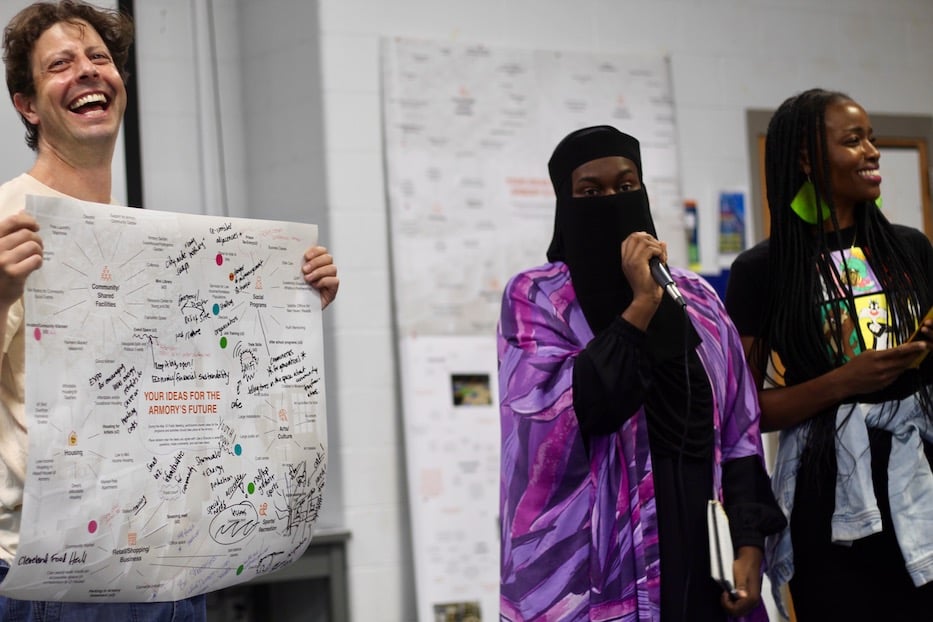

Elihu Rubin with Salwa Abdussabur and Hafeeza Turé.

“We want to build the momentum and keep the momentum until we can really develop some ideas and a path forward for the Armory,” said Elihu Rubin, an associate professor of urbanism at the Yale School of Architecture who has been working to revitalize the Armory since 2017. “It’s going to take a lot of work to fix the Armory. It’s a big lift.”

It marks a potential period of change for the building, which was first built in 1930 and handed from the state to the city after the National Guard left it in 2009 (read more about its history in previous Arts Paper reporting here, here, here, and here). In the past two decades, multiple attempts at revitalization have been marred by false starts, circular discussions, and a lack of sustained and sustainable funding for the space.

There were, for instance, whispers of an incubator kitchen, a new home for the city’s Board of Education, an open space where arts events like Artspace’s City-Wide Open Studios could take place all year. There was a time when it looked like the Armory, rather than the Dixwell Community Q House, would receive significant city support. And then, each time, those efforts fizzled out. “We can’t let that happen again,” Rubin said.

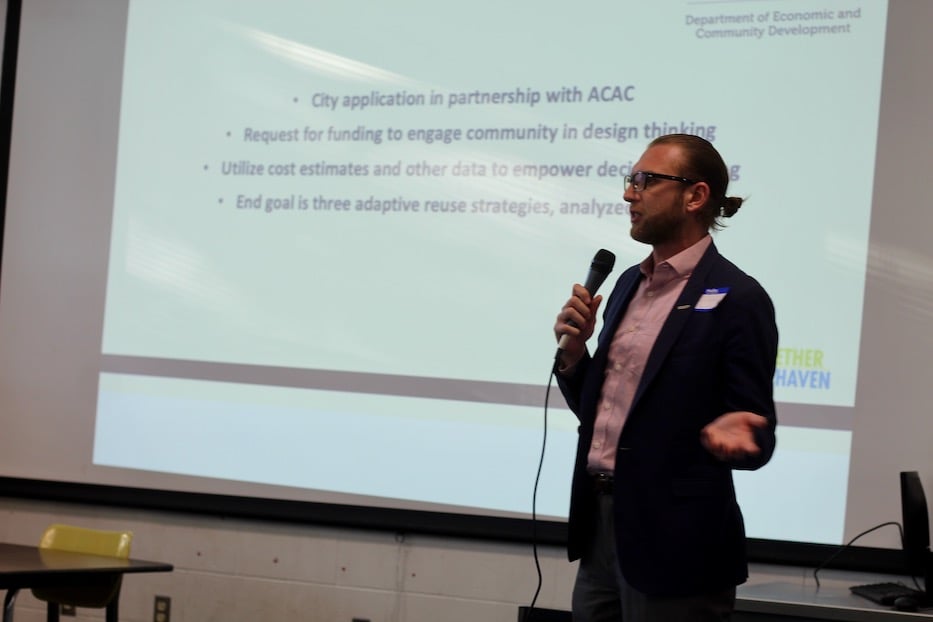

New Haven Economic Development Officer Dean Mack.

He pointed to several of those efforts as case studies in what not to do. Eleven years ago, for instance, then-Alder Claudette Robinson-Thorpe and former city Chief Administrative Officer Rob Smuts applied for $2.8 million in state funding, an amount that would begin to transform the Armory into a community center. But the aldermanic leadership changed, and the city ultimately shifted its focus to restoring the Q House, which received $15 million in state support.

Now, the city is in the running for a $200,000 planning-focused Connecticut Community Investment Fund grant, on which it has partnered with the ACAC. New Haven Economic Development Officer Dean Mack said that the city expects to hear about the grant in September.

The city is also working with architect Georges Clermont and his Ansonia-based architecture firm AEPMI to create an updated study of the building. Mack said that Clermont and members of his team have already visited the building several times, documenting its deteriorating condition.

They have already drafted a report that outlines significant water damage, asbestos, and code violations, as well as weight-bearing limitations and a roof that is all but caving in (the city is currently doing $100,000 of emergency work on the roof, for which it has contracted with Eagle Rivet Roof Service Corporation). For instance, the building’s mezzanine currently supports 30 pounds per square foot—but current code mandates that it should be at least 125 pounds. Nothing is ADA accessible.

When finalized, Mack said, the report will go out to an estimator, and give city officials a sense of how much money will need to go into a revitalization for the building. Across the country, similar Armory rehabs have ranged from $55 million in Saint Louis to $85.2 million in Jamaica, Queens to $65 million in San Francisco, where the future of the building is still uncertain.

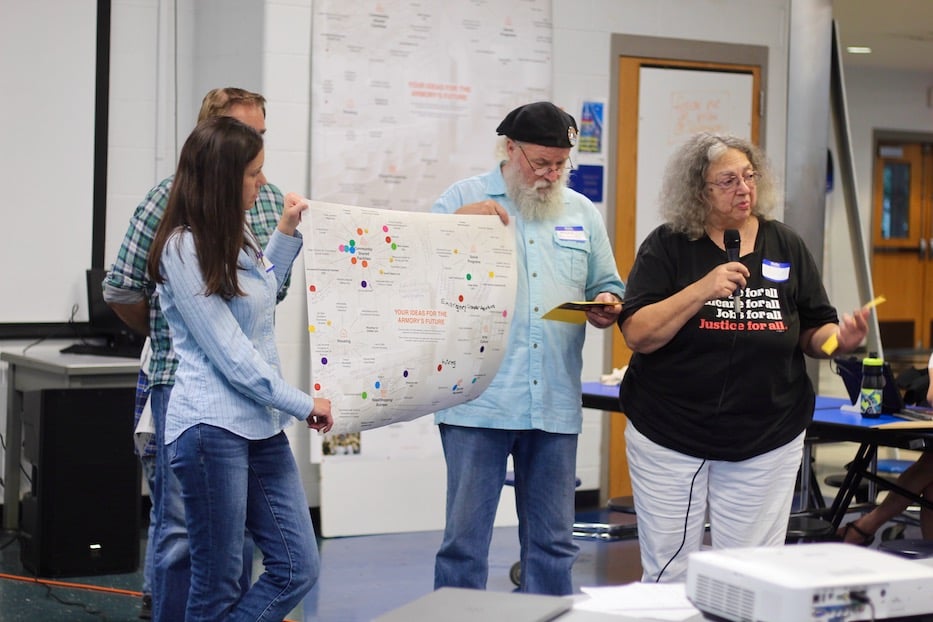

But the bulk of the evening went to attendees’ memories of the Armory, and hopes for its future. On each of the room’s tables, illustrations from May’s brainstorming session stretched across the round surfaces, with smiley face stickers and color-coded dots that could stand in for approval, applause, or disagreement. One displayed other models of adaptive reuse, including Pittsburgh Yards, New York City’s youth center The Door, and Parkville Market in Hartford.

Another recapped potential uses of the Amory, from a roller rink to a daycare center to affordable housing for artists. Place stickers on the ideas you agree with, suggested a prompt at the center of the sheet. Use a Sharpie to write questions, make comments, and add new ideas. Pieces of cardstock displaying other Armory rehabs fanned out across the table.

Charlotte Leib and Arden Santana.

At a table close to the front of the room, close friends Arden “Fire” Santana, Shayla “Earth” Streater, and Hafeeza “Wind” Turé—a.k.a. The Elements of Abundance—huddled around the sheets, starting to dream about what they’d like to see. As she took a seat across from them, artist and Black Haven Founder Salwa Abdussabur jumped into the discussion. Architectural historian Chris Wegren and historian Charlotte Leib weren’t far behind her.

Wegren cleared his throat and asked what people would like to see. The question hung over the table for a moment, as if participants were thinking about how close they were to the stately old building, which sits less than three blocks away. After a beat, the response was almost immediate. As they spoke one by one, chatter rose across the room.

"We are very much concerned with community economic development,” Santana said, outlining a vision for a thriving Black business hub that is part of her mission as the founder and director of SĀHGE (Science, Art, History, Government, Economics) Academy. Nearby, her daughters Nevaé and Santana Brightly outlined a year-round Black Wall Street. “Like the one that was in Tulsa,” Nevaé said.

Nevaé and Santana Brightly.

Turé nodded, noting the need for a community hub like the old Q House. As a lifelong New Havener with deep roots in the city—her great, great, great, great grandfather was a pastor at Varick Memorial Zion AME Church on Dixwell Avenue—she can still remember decades when the Armory was still very much active. While those may have passed, she still feels like she has a stake in its future .

Around her freshman year at James Hillhouse High School, a group called Elm City Nation tried to bring back the Black Expo, which made Armory history in the 1970s. Leading those efforts was Scot X. Esdaile, now the president of the Connecticut State Conference of NAACP Branches. Turé, who was 13 at the time, remembered the event running for at least two years.

“I’ve had the privilege of seeing the Armory in many iterations,” chimed in Abdussabur, who is a third generation New Havener and grew up in Beaver Hills. She jumped ahead to the early and mid 2000s, when she participated in Artspace New Haven’s City-Wide Open Studios. In 2017, she was part of a “Literary Happy Hour” in the space, reading poetry that bounced off the high ceilings and old, listening walls.

That was six years ago. Having seen the artistic potential that the building holds, she said, she’d like to see it become a home for artists and creatives, particularly those who have long been relegated to the margins. For years, she’s seen artists and developers alike make attempts toward affordable housing and studio space, only for the projects to go belly up.

She’s much more excited about the potential for creative space than a grow house or dispensary, she added. Looking over a brainstorming sheet from May, she crossed out the idea for cannabis entirely and signed her initials beneath it. Turé and Santana joked that maybe hemp, with which people can build sustainable materials, might be a more happy medium.

She’s much more excited about the potential for creative space than a grow house or dispensary, she added. Looking over a brainstorming sheet from May, she crossed out the idea for cannabis entirely and signed her initials beneath it. Turé and Santana joked that maybe hemp, with which people can build sustainable materials, might be a more happy medium.

“What are we trying to cultivate?” Abdussabur said. She pointed to the need for a community incubator kitchen, which could have helped her mom’s small food business take off with fewer municipal headaches. “It has to be creative … this could be a place where people can come, where innovative entrepreneurs have a space to thrive.”

Streater, who grew up in Beaver Hills, remembered driving past the Armory many times, but never going in. It wasn’t until Artspace opened up the building a few years ago that she entered it to see a performance from the artist Shaunda Holloway, and stayed to explore the space. “I really saw the building,” she remembered. “It was beautiful.”

Half a decade later, she’d like to see a dedicated corridor for holistic health and wellness, including a gym and spa, as well as a place for non-Western healing practices. During the meeting in May, wellness was often a central point of discussion, including for Turé and the Zola Experience Founder Katurah A. Bryant.

Holding up a card printed with the Harlem Armory, which is run by and offers youth programming through the Harlem Children’s Zone, Santana suggested the importance of a safe space for youth. She was far from alone: many of Wednesday's attendees centered youth in their hopes for the Armory’s future.

One table over, Armory Community Garden members Amelea Lowery and Rahina Nabali both pointed to the need for any plan to keep the garden—or a garden—intact at the building. Each week, the two are among a handful of urban gardeners and farmers who come out to grow their own food, care for the space, and spend hours of their weekend together cultivating the land on Goffe Street.

“It’s so healing,” Lowery said, adding that growing one’s own food is a humbling reminder of the amount of labor that goes into food systems—and of the waste that is part of monoculture. “I think the biggest part is the community participation.”

At a table near the back of the cafeteria, longtime Edgewood resident Lensley Gay tried to remember the last time she was inside the Armory. As a teenager growing up in Norwalk, she and her friends visited the space in the 1970s for a concert, walking the two miles from Union Station. Decades later, she’s not sure what she wants to see in the building—but knows that she wants to see it occupied and thriving.

“It felt like coming to New York,” said Gay, now the site coordinator for the Family Resource Center at Brennan Rogers School. “It was lively. We had that excited energy. Coming back to the train station, we felt like we’d done something big.”

A youth center was among several of the night's proposed ideas.

Next to her for most of the meeting, Rev. Lucille Brown advocated for a space like The Artists Collective, a youth arts center nestled in the heart of North Hartford.

The space, which has received national recognition from the President’s Committee on the Arts & the Humanities, is an example of adaptive reuse that exists entirely for young people. Brown, who grew up in New Haven and worked for the Department of Children and Families for 37 years, wants to see a safe place for New Haven’s kids to go after school.

“This is the model I would suggest taking a look at,” she said, pulling up the collective’s website and scrolling to a long list of funders. In New Haven, “I drive by and look at the [Armory] building, and I say, ‘What are they doing with it?!’”

Other attendees piped up multiple times throughout the evening. Sean Reeves, who has helped found and run Father’s Cry Too, S.P.O.R.T. Academy and the Community Economic Development Partnership (CEDP), urged city officials not to leave New Haven companies and small businesses out of the conversation.

“How far have you thought about the companies that are going to do the work?” he asked from a table bathed in evening sunlight.

City Deputy Economic Development Administrator Carlos Eyzaguirre said that because the City of New Haven owns the building, the city’s guidelines for Black and Latino, women-owned and small businesses contractors will ultimately apply to any renovation. That means that after a feasibility study is finalized and before work can begin, the city will send out a request for proposals (RFP) to which contractors can respond.

Paula Panzarella (at far right): "“It was an incredible experience for me, the way everyone was pulling together in New Haven and showing solidarity."

Peace activist Paula Panzarella, who lives close to the Armory on Norton Street, advocated for a space dedicated to emergency response and mutual aid, particularly in times of community crisis. Shs remembered working with fellow New Haveners in August and September 2005, when the National Guard designated the Armory as a space to amass and store supplies following Hurricane Katrina.

“It was an incredible experience for me, the way everyone was pulling together in New Haven and showing solidarity, with the mess of Katrina because our government was not doing anything,” she said. Snaps and meditative Mmmmhmms multiplied across the room.

Before the end of the evening, Rubin assured attendees that conversations would continue and move forward, particularly around potential sources of funding for the building

For more on upcoming meetings, visit the Armory Community Advisory Committee (ACAC).