Immigration | Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services (IRIS) | Long Wharf Theatre | Storytelling | New Haven Free Public Library | Theater | Tower One/Tower East | Arts, Culture & Community | CMHC

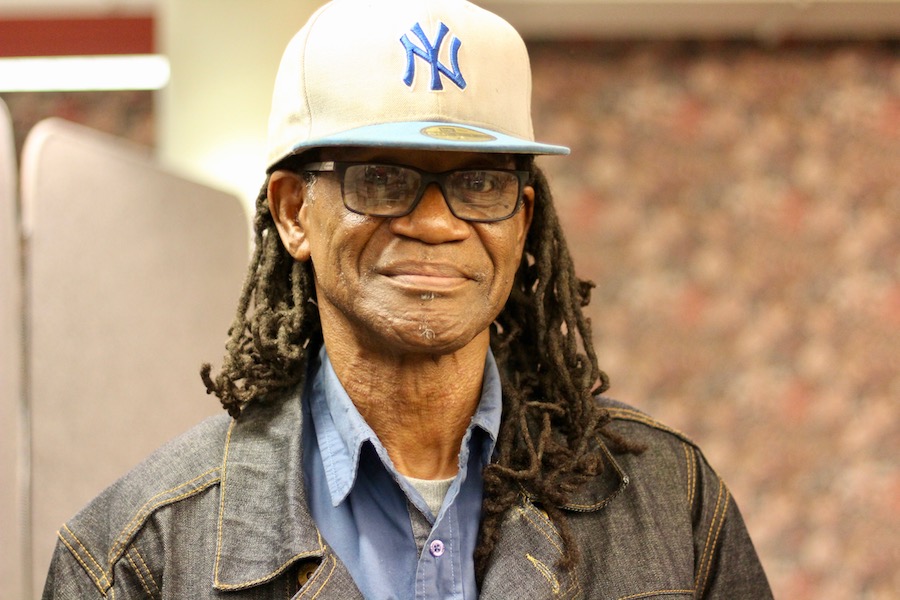

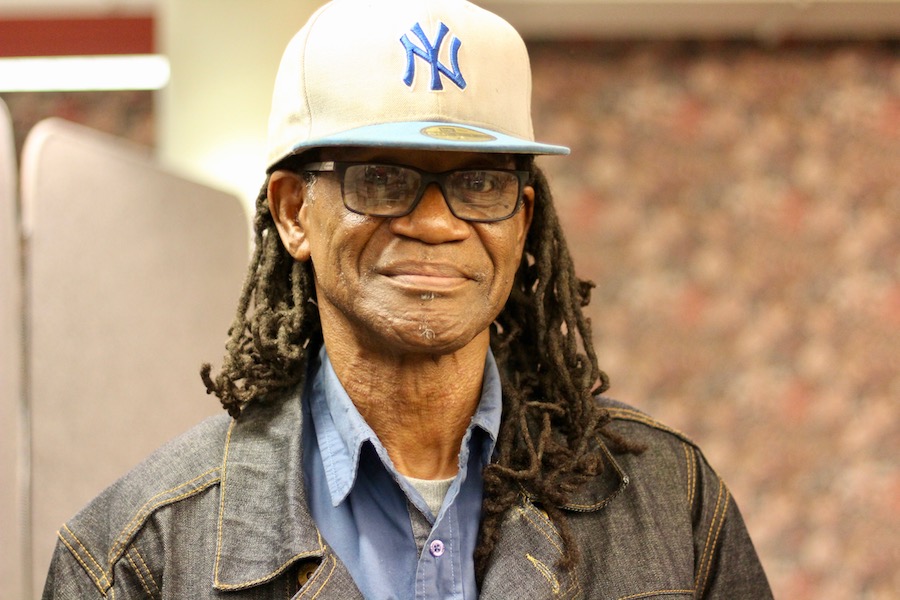

| Edward "Ed" Trimble Monday night. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

Edward Trimble was standing alone at one end of a chess board. He looked around him: small, sleek pawns all in a line, ready to lurch forward. Across 64 squares he could see the opponent’s king. He wanted to be that king. The only question was: how was he going to get to the other side?

Monday night, Trimble was one of over 20 New Haveners to bring his story to the New Haven Free Public Library (NHFPL) for “Tell Your Story: Finding Home,” a collaboration among Long Wharf Theatre, Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services’ (IRIS) Young Leaders Program, “Survivors of Society Rising” at Connecticut Mental Health Center (CMHC), and residents of the Tower One Tower East assisted living facility. Several community members also came out to read.

The groups came together through the New Haven Play Project at Long Wharf Theatre, as well as Long Wharf’s seven-year partnership with the library. A culmination of this year’s play project is scheduled for the end of June.

“One of the most powerful human needs is to feel heard and be seen, and story is a really powerful way to do that,” said Elizabeth Nearing, community partnership manager at Long Wharf. “We know that this is just a portion of the multitude of stories in our community.”

| Michaelle Gonzalez, who spoke about housing instability in New Haven. "I think home is kind of overrated anyway," she said to laughs as she read. |

Like Trimble’s, which began at the edge of a chess board that was also his life. Across the board’s black-and-white expanse, he caught sight of a piece that stopped him in his tracks: the king, second in power only to the queen. The piece called out to him. But when he tried to move toward it, he found that he was a pawn, feet heavy.

“Home was king, but I couldn’t find my home,” he began. “Because I’m traveling through 64 squares as a pawn. I’m traveling through each square, trying to find my way home.”

Trimble continued forward, eyes fixed on the king. He met a bishop, watching him “day and night” until he had mirrored his actions so convincingly that he had become the piece itself. Then he met a knight and shape-shifted again, soon coasting across the squares in that classic L shape that only a knight can make. On the board, it started to rain. He came to a castle and met a queen who invited him inside.

“On my way home, she said close your eyes, and tell me what you see,” he recalled, closing his eyes as he spoke. At first, Trimble saw nothing. He didn’t know what to say. And then shapes began to emerge from the dark.

“I’ve got my eyes closed, and I’m trying to go back home, and I said, blackness,” he said. “I see a pawn there. I see a bishop there. I see a knight there. I seen all things in the blackness, because everything comes from the blackness.”

But the king still wasn’t there. Trimble went back to the board, traveling back across all 64 squares. When he reached the place where he had started, he came to a man with a big mirror. It startled him to realize it was a reflection of him. It had been there all along.

“I found my way home,” he said to loud applause and cheers from the audience.

| Pedro Hanlan: "It’s like a letter from my old self, because if you see me today you would never know the trials and tribulations that took place." |

Other stories came to the audience through poetry, personal anecdote and even a spot-on approximation of a dog’s fierce and territorial yap. From CMHC, New Havener Betty Williams gave a raw spoken word piece, tracing her trajectory from a young girl in South Carolina to a life turned upside down by the crack epidemic to a failed, terrifying marriage and safety in New Haven. A poet who introduced herself as Africa told the group that she's found home in herself, after drawing a bridge between her struggles, her lineage and her future.

Delores Alleyne, a resident at Tower One/Tower East, spoke candidly of her fear of war, recalling how she would silently pray at all hours of the day during the Cold War and Cuban Missile Crisis. Years after praying herself to sleep, she realized that it had strengthened her relationship with God.

Fellow Towers resident Carlis Highsmith described a different struggle, walking the audience through years as a young mother with three children, working for the State of Connecticut as she tried to build her own education. She encouraged others in the room to try to learn one new fact every day, to "start from the bottom, but keep going."

"We're a family now, because we share," she said to attendees. "That's what families do. Share and love, and love each other."

Pedro Hanlan, a 23-year-old Edgewood resident, recited a poem from memory, drawing cheers from the audience as his bars flowed into each other. He took the audience back three years, when he was sent to a disciplinary program. At the time, he said, he was dealing with an abusive environment in which drug addiction was present.

Growing up was hell, you can tell by all the medicine

Prescription written test was given like a specimen

I felt obliged to die inside a fiend with exo-skeleton

and I’m still alive? Scribbled notebooks in my mirrors

I’m spitting that Doctor Seuss but the content is not for children

Pill bottles swallowed father with strong aggression

My life lessons still seem to imperfection

Therapy session gone with reaper tensions

I’m selling my two cents to the devil like repossession

“It’s like a letter from my old self, because if you see me today you would never know the trials and tribulations that took place,” he said in a text message afterwards. Now he frequents Youth Continuum on Grand Ave., and is saving money to take classes in marketing. A new sense on consistency in the city has become his home.

| Melba Flores: “I didn’t realize how much my family and my community defined that home is New Haven." |

Others had to leave home before they found it. Prefacing her words with an excerpt from Sandra Cisneros’ The House On Mango Street, 22-year-old Melba Flores explained that she didn’t actually know what—or where—home was until she moved away from it for college. Born and raised in New Haven, she decided to attend Kalamazoo College in Michigan after realizing that “I just needed the space.”

But when she got there, she found that there weren’t other students from New Haven, or even from Connecticut. She was fairly certain that there were no Latinx students from anywhere on the East Coast. She struggled through her first year, and then her second, and then her third. By the time she was a senior, she had decided to return to New Haven after school. The city had not always been kind to her—she lived in several run-down apartments, including one where the roof caved in—but it was home.

“I didn’t realize how much my family and my community defined that home is New Haven,” she said. “But then, I realized that even though I’m far away, it doesn’t mean that I can’t make home this place that doesn’t feel familiar at all. It doesn’t mean that I can’t connect to other people.”

Now that she’s graduated and returned, she said, New Haven doesn’t always feel like the home she left six years ago. But she doesn’t want to go back to Michigan, either. So she’s developed a third place that she can call home: herself.

“Sometimes with that, you have to make yourself home,” she said. “I’m recognizing that the more I start loving myself, the more and more other places start to feel like home. And I have that.”

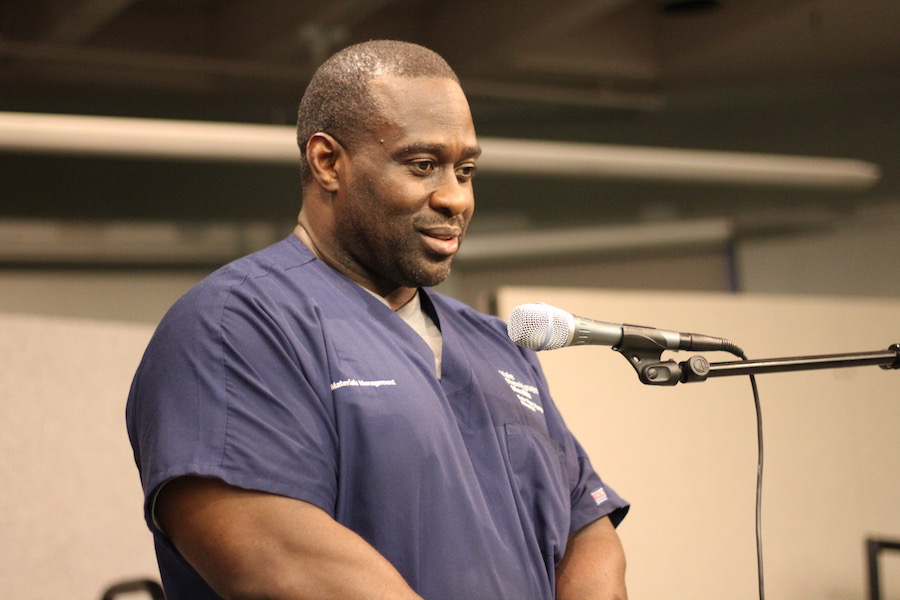

| Joe Jackson. |

For others still, home remains an evolving concept. Joe Jackson, who grew up in Hamden and now lives in West River, told attendees that “I grew up wondering what home was like.” One of seven kids, Jackson found home in sports for many of his early years, excelling in basketball and baseball at his school.

But at home, his relationship with his dad was strained. Because of work, he never came out to any of Jackson’s games. As he traveled around the state, Jackson saw a different model: dads who made time for basketball games, then ate dinner with their families afterward or took their kids out for celebratory meals and donuts. That didn't seem like it was in the cards for him. At one point, Jackson said, even the then-mayor of Hamden even came to his house to insist that his dad see a game. No dice.

“It never felt like home to me,” he said. “I never held hands with my father, I never heard my father say he loved me. All he did was work. As it went on, I was just wondering—why wasn’t my home like their homes? I could feel the love, I could feel the compassion they had for one another. I was wondering why I never had that at home.”

In high school, Jackson was kicked out of his house because he refused to cut his hair. He bounced around, ending up with a VISTA fellow for a while before living with one of his older brothers. He stopped speaking to his dad for two decades. When they did talk 20 years later, Jackson never asked him why he’d seemed so distant all those years ago.

Instead, he vowed that he would be a different kind of dad. When he was graduating high school, Jackson thought about trying to go into professional sports. But he had a daughter on the way, and decided to stay in Hamden.

“I was thinking to myself, I could have a future,” he said. “Because my past wouldn’t let me have a present.”

| Divine Mahoundi: Home is everywhere. |

A refugee from the Republic of the Congo, Divine Mahoundi closed the evening with another shifting notion of home: that it is everywhere, because it is elusive. Raised by her grandfather until she was 10, Mahoundi grew up away from her parents and other siblings. She knew her father’s name, she said, but that was it—she never saw any photographs of him, or met sisters and brothers that she heard about.

When she was 10, she was reunited with her father, but “things start kind of messing up,” because he was in the military. Home became a place of violence and fear. She came to the U.S. as an asylum seeker in 2016. Now a senior at James Hillhouse High School, she described saying goodbye to her grandfather in tears, unsure of whether she would ever see him again.

“I don’t know when you’re gonna come back, if you might find me,” her grandfather told her before she left. “I don’t know if you’re gonna find me again, or if we’re gonna see each other again. But don’t forget, your home is everywhere. Everywhere you go as long as you keep me in your heart, you keep all the family in your heart.”

Mahoundi took those words with her to the U.S., where she had to start over. Each day after learning new English words, she would head to her bedroom and pull out photographs of her grandfather. Yes, she assured herself. Home could be everywhere. And he could be home with her.

As a young leader with IRIS, Mahoundi said she’s now finding home in fellow young refugees, including a group of high school women she refers to as “my sisters from another mother.”

“This city gave me another chance,” she said. “A new me. A new person. A person who can bring something to this society. So this is my home, because home is everywhere.”