Ely Center of Contemporary Art | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts

| Bookends by Mindi Rose Englart and Lily Grace Sutton. Lucy Gellman Photos from the exhibition. |

It may be the book that first catches your eye, with its blocky and all-caps burgundy print and white background. A clean green band wraps the spine like an invitation to look inside. On both sides, you’re drawn to something else: bundles of paper and twine, brick and yarn, taut and pink like the flesh of a very ripe grapefruit.

Mindi Englart and Lily Sutton’s Bookends is one of over 100 works in Our Bodies Ourselves, on view at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art (ElyCoCA) now through April 10. One of two exhibitions this month to explore what it means to have a female body in this specific moment, Our Bodies Ourselves takes a look at the eponymous book five decades after the book came into being.

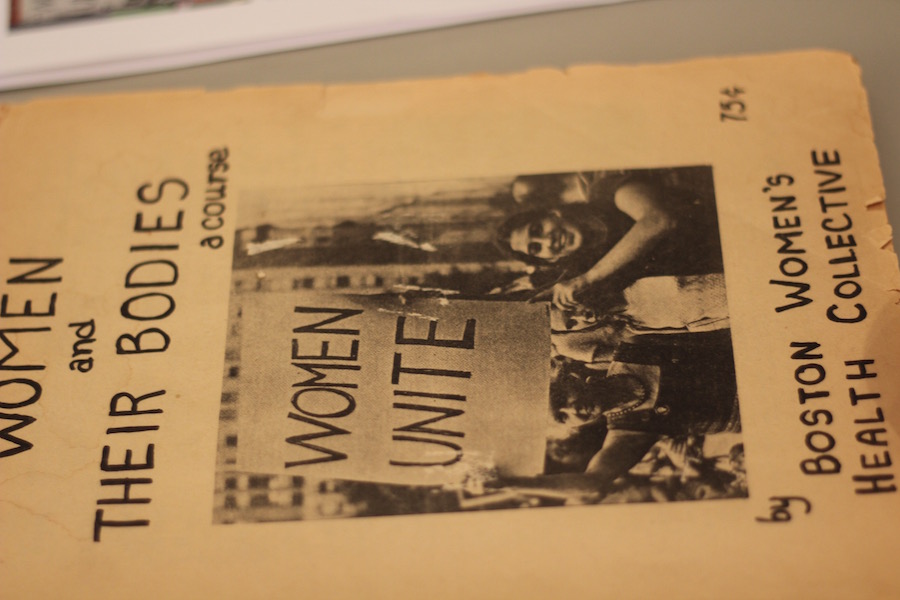

| An original copy of Women and Their Bodies. |

The story of Our Bodies Ourselves begins almost five decades ago not in New Haven, but in 1970s Boston with something called the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, itself an outgrowth of a women’s conference in the city at the end of the 1960s. By the early 1970s, the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective published Women and Their Bodies, a textbook on women’s health that was by and for women.

It outlined puberty, venereal disease, pregnancy, abortion (which was not yet legal) and birth in and outside of hospitals without any sort of stigma. The following year, the book was reprinted by New England Free Press as Our Bodies Ourselves, and later adopted by the larger publisher Simon & Schuster. Since, the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective has rebranded and expanded its mission as Our Bodies Ourselves.

Since the 1970s, the organization has issued reprints every seven years, to account for new material and policy, as well as updates in reproductive health. Last year, the organization announced that it would stop publishing updates, because they were becoming too costly.

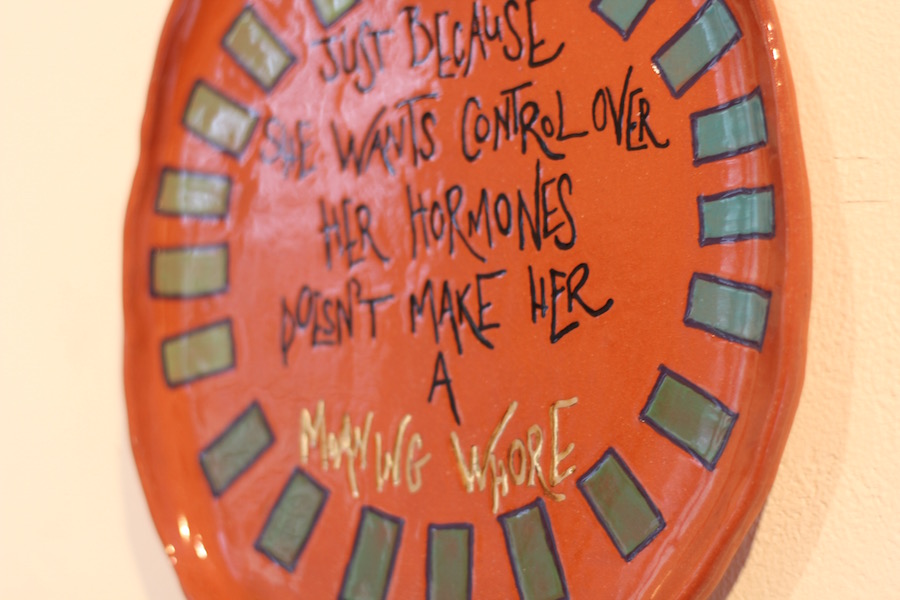

| A detail from Dani Sigler's Birth Control Plate Series |

At the Ely Center, the exhibition does not just respond to the material in the book, but opens a multigenerational conversation with it. On the first floor, it is hard not to be drawn to the yellow-blue light of Gestation from artist Megan Shaughnessy, a video and installation that takes the viewer through three trimesters of pregnancy. The artist has used herself as a subject, symptoms of pregnancy crowding in over her face in white text as the video begins.

A cool, clinical voiceover reads off markers of each trimester, from mood swings to movement of a fetus to the final stages a body goes through before birth. Each is interspersed with quotes—first from author Brett Kiellerop-Morris, who sees pregnancy as preparing women for the exhaustion of motherhood, and then from several men who praise the beauty of pregnant women and seem deserving of a severe beating with a hot teflon pan.

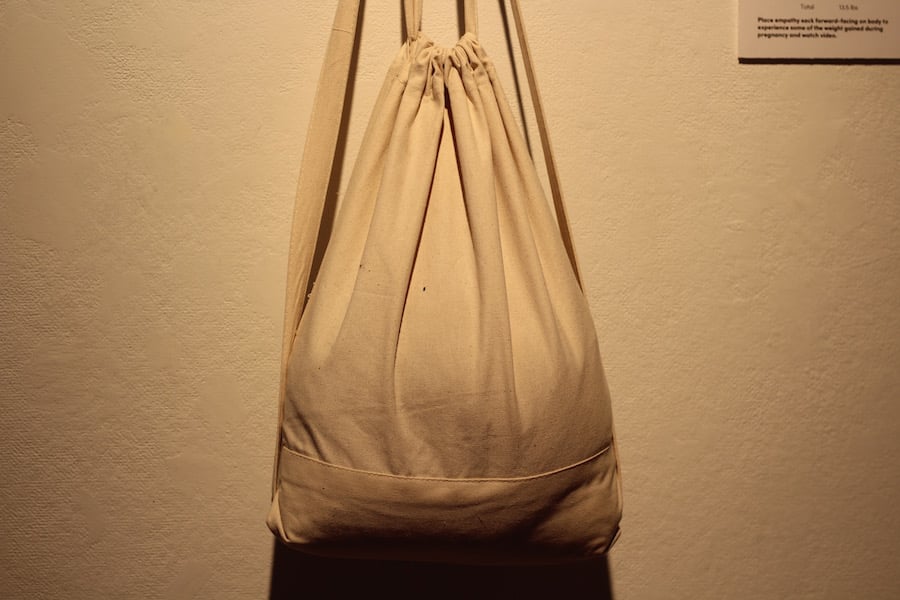

| A sack that hangs with the video from Gestation. |

On the back wall, a white cloth backpack hangs with its weight centered, waiting for a viewer to pull it on. At 13.5 pounds—that’s the weight of a baby, plus placenta, plus amniotic fluid, plus uterine muscle—it gives the viewer something to wrestle with as the exhibition becomes interactive.

Through different lenses, Gestation becomes any variety of things: wildly effective birth control, a lesson in humility for the uterus-less among us, truth spoken to power, an invitation to dismantle an obstetric establishment that isn’t working. It’s a call to arms, just as Our Bodies Ourselves was decades ago. Do better, it commands. Our lives and the lives our children literally depend of it.

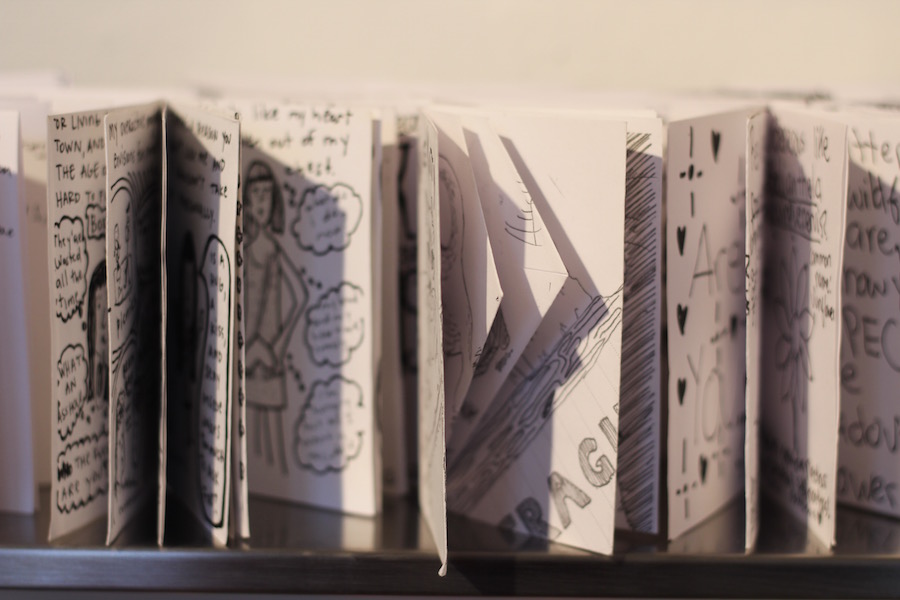

| The exhibition features both zines from Englart's students at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School and from artist Aly Maderson-quinlog. |

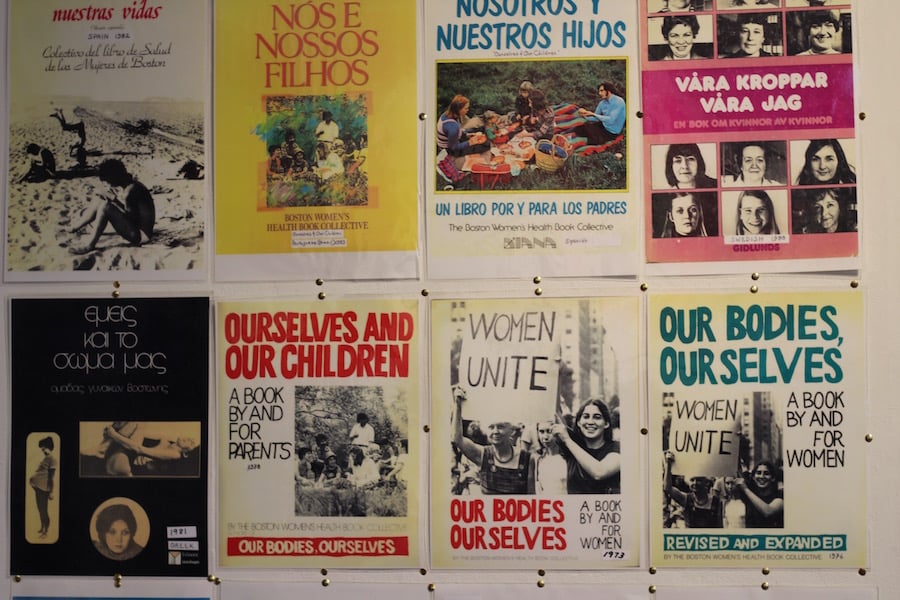

Nearby on the first floor, several artists have taken other interpretations on the text. To the right of the center’s lobby, two plush pink pillows wink out behind Englart and Sutton’s bookends, which reveal a mother and daughter living with two like, but very different, bodies. Around them, the room becomes a sort of living library, tracking the evolution of Our Bodies Ourselves on one wall while presenting a wholly contemporary “zine library” on another.

In her Kitchen Sanctum also on the first floor, Global Local Gourmet founder Nadine Nelson has created a room where women are invited to both eat, and to take time to reflect on what they would like to foster in themselves. The care with which she invests herself is a work of art—she will be holding “Kitchen Wellness Wednesdays” each week—and so is the space, set up with warm wood furniture and work by collage artist Clymenza Hawkins and others.

| Nadine Nelson asks an attendee what they wish to blossom at Sunday's opening reception. There are events in her Kitchen Sanctum all month. |

Upstairs, artist Joan Fitzsimmons has produced a visceral and deeply satisfying piece in The Healing Arts, a collage of photographs from her knee surgery last year. Visible from the stairs, the images have an alien quality, as if they inhabit some world that cannot possibly be ours. But the longer we examine the topography of her body, the more it reveals itself: chocolate and wine-colored bruises, stapled skin that looks like a worm coming up from the soil.

Printed on velvety photo paper, the images are a sort of testimony—to pain, to age, to the fact that a body is an intelligent machine, but a machine nonetheless. But there’s also something distinctly womanly there: the body’s ability to heal from pain, sometimes unthinkable, and move on.

| A detail from The Healing Arts. |

That kind of behind-the-scenes peek at psychology takes on a different life in Martha Lewis’ Warm, Wet and Noisy, a bright and frenetic diagram of the artist’s brain accompanied by three “brains” made of gem-like stones, a big yellow sponge. and a dried out quarter of red cabbage. And again in Neil Diangle Orians’ second-floor installation, which asks what it means to involve the queered male body without any words at all.

It explodes into words with Nicole Gugliotti’s awe/agency, a multimedia installation where bulbous ceramic shapes turn into earpieces, through which one can listen to women talk about their brushes with reproductive healthcare in the U.S. (listen to the audio here). In a system that is so broken, there are victories here—women who are confident in their abortions, who have done something that is brave and smart instead of desperate, stigmatized and deeply traumatic.

There is surprising intimacy in the piece: one must lean in to the cool porcelain to hear the women’s voices, as if they are there in the interview room with them. But Gugliotti also makes a pragmatic point: this should be seen as a standard reproductive procedure, no different than getting a copper coil inserted or removed, or picking up a pack of birth control at the pharmacy.

While the works may take a wide interpretation on the book, curators have also programmed several events that specifically engage Our Bodies Ourselves, past and present. At an opening reception last Sunday, a multigenerational panel of doctors, public health advocates, and original authors of the book took on the question of where feminism might go next (watch the full video here).

| awe/agency close-up. |

Throughout March and into early April, there are workshops for zine making, movement and meditation, nights reserved for music and poetry, and “Kitchen Wellness Wednesdays” with Nelson, who will hold themed discussions inside her Kitchen Sanctum installation.

For Joan Ditzion, one of the founders of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective (she has since worked on every reprint of the book), it’s a striking way to keep Our Bodies Ourselves alive while looking at how it has evolved.

“Although time has passed, it’s such a joy to be able to have this gallery, dedicated to the memory of a woman in the arts, invested in this visual work,” she said on Sunday, haloed by a detail of Fitzsimmons’ knee as she spoke. “For me, having worked on this project was probably the most informative project of my life.”

Ditzion recalled growing up in a society where, despite social justice-oriented parents, she constantly felt inferior to the men around her. Only after she became involved in women’s liberation work did she adopt “a women-centered view of my body and myself,” she said. Her words echo throughout the exhibition, from Jean Marie Casbarian’s pomegranate-stained nightdress to Susan Clinard’s arresting Mother and Child at the top of the stairs.

Indeed, Our Bodies Ourselves leaves viewers with a deeply physical sense of where women have been, and where they may hope to go next. It's not perfect, but that learning feels like part of the process itself.

This is not the radical—and still needed—call to arms that acknowledges the way white women have upheld systems of oppression for their gain, and erased their Black, Latinx and trans sisters from American history in the process. This is not the show that explains why it is more important to teach Audre Lorde and Bell Hooks than Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan, or at least chuck The Feminine Mystique for From Margin To Center.

But it’s a start. A good one, with glimmers of intersectional feminism as it invites new artists and practitioners to the table. Even as Our Bodies Ourselves stops publishing, we sense that there will be another chapter based around this work. And we await it with eager, open eyes.