Arts & Culture | Nasty Women New Haven | Visual Arts | Yale Divinity School

| New Haven artist Howard El-Yasin lifts the veil on one of Aly Maderson-Quinlog's pieces. Lucy Gellman Photo. |

There’s the neat rectangle of lace, then the figure in black and white underneath. There, staring back with a face like glass, is Rebecca Ann Lattimer Felton, the first woman to serve in the U.S. Senate. Her hands sit gingerly by her lap. Beneath her, in the folds of her skirt, a spray of red text take over.

“I do not want to see a negro man walk to the polls and vote on who should handle my tax money, while I myself cannot vote at all,” it begins. “ … If it need lynching to protect women’s dearest possession from the ravening human beast, then I say lynch, a thousand times a week if necessary.”

Long after the end of her life, Felton has become part of Complicit: Erasure of the Body, the third annual exhibition from Nasty Women Connecticut. After the launching with a 2017 exhibition downtown after the 2016 election of Donald Trump, the group has expanded to hold not just annual themed exhibitions, but also panels and workshops, an annual film festival, and ongoing #MeToo testimonials project.

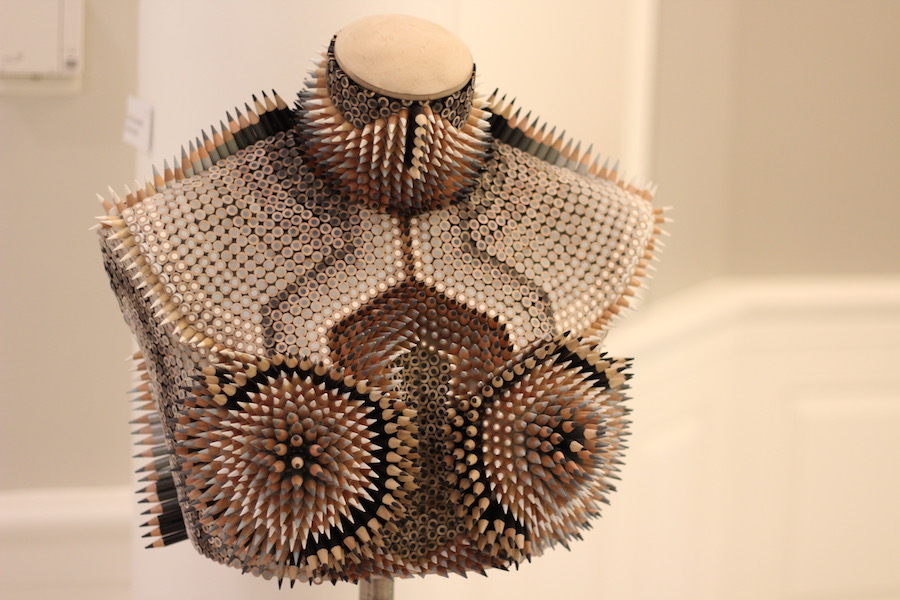

| A detail of Shelby Head’s Power Figure. |

Over 160 artists are featured in the current show, which runs through March 31 at the Yale Divinity School on Prospect Street and has a full month of events planned with the exhibition. Over 1,000 people attended an opening reception Friday evening.

“Amplifying voices became something that was super important to us,” said Louisa de Cossy, one-third of Nasty Women Connecticut with Attallah Sheppard and Lucy McClure. “Bringing people’s voices in to see other events.”

This year, the exhibition’s location emerged midway through nomination hearings for Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, by which de Cossy said team members were “all kind of triggered.” Not long after Professor Christine Blasey Ford gave her testimony, the three heard from Laura Worden, a student and curator at the Divinity School.

Worden found herself thinking about Kavanaugh’s own history with Yale, and suggested the Divinity School as a possible venue for the group’s annual show. Soon, the four were working through the show’s logistics and theme, which probes the limits of complicity—to what degree one has helped commit an act of wrongdoing—as it pertains to sexual violence.

| Molly Gambardella's Shame Shield. Of the piece, Gambardella wrote: This was one of those pieces that went together very quickly because I knew exactly what I had to say, I had intention ... pencils worked so well to create two different textures, the slices look similar to chainmail armor, and the points of the pencils look prickly as ever. |

Despite their excitement, de Cossy said all four also thought about what it represented to take the exhibition out of downtown and put in into an institutional and literally sacred space.

“When we entered into partnership with Yale, we were really conscious of what that meant,” she said. “Because Yale is complicit to a lot of events that happen to a lot of people here. So a lot of the work speaks to that. And the fact that Divinity [School] was open to the space meant a lot … it’s definitely across the community.”

The group has involved several community partners, rolling out collaborations with the New Haven Pride Center, Black Lives Matter New Haven, Artspace New Haven, and the Yale Center for British Art among others.

Now, almost 200 works line the school’s first-floor hallways, replacing clean off-white walls with bodies in various states of injury and undress, breasts and uteri that exist all of their own, and depictions of the Virgin Mary as an exhausted, tried and muted woman. A wash of almost entirely desperate or frightened female faces, they are difficult to take in all at once, warranting a second or even third look.

| Sara Zunda's Growth. |

There are works like Sara Zunda’s Growth, an illustration small and tucked away enough that it’s easy to miss at first glance. In the piece, a woman stares from the frame, her hair haloing a face that looks absolutely exhausted. Her palms reach out, right hand grasping left thumb. Her nail polish matches her lipstick and eyeshadow, all of which are red. Bits of foliage wrap through her hair and up her wrists, a seeming nod to the Garden of Eden that could also hold Naomi Alderman’s The Power.

Or Linda Cardillo’s Innocence Taken, a multimedia installation that hangs on the side of a hallway. From a background designed to look like brick and driftwood, a three-dimensional face emerges, shiny and chrome where flesh should be. Silvery gauze and webbing stretch across her face, blooming out behind her. Maybe she is a necrophilic Marianne, symbol of the French Republic gone all wrong.

| Detail of Linda Cardillo’s Innocence Taken. |

Or she’s the very ghastly thing that happens to women when that friend gets too close, or that college party doesn’t stop where it’s supposed to, or that doctor gives a pelvic exam that is not hippocratic at all, or that employer thinks that silence is the price of one’s job. We can lean in close and never hear what she has to say: her mouth is covered by layers of fabric. A white flower, perhaps a symbol of what once was, sprouts through her right socket.

Others take a wider, almost theoretical approach. As viewers enter the exhibition, artist Patti Maciesz has invited them to “Bill The Patriarchy” with a huge, eye-catching installation in red and orange marker. With a series of charts that spread across the wall, she has diagrammed out what that means in terms of uncompensated labor.

In a sliding glass case nearby, multimedia artist Zohra Rawling has submitted her own take on erasure of the body with her Snow White, a ceramic oval with an bulbous, red and blue eel, and words by local writer, editor and musician Brian Slattery.

“Maybe it shows that Snow White isn’t really what you thought it was,” she said at Friday’s opening.

| Babz Rawls-Ivy is a first-time exhibitor in the show. |

But the most moving works in the show are those that speak the theme right into being, then turn the school’s ostensible sublimity on its head. In Aly Maderson Quinlog’s Lift The Veil, five identically framed portraits of early suffragettes and woman politicians sit waiting for the viewer, each beneath an identical rectangle of paper thin, ornate white lace.

When those strips are lifted, the full impact takes a minute to take hold. Under a portrait of each figure—Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Felton, Carrie Chapman Catt and others—words jump out in red, inscribed in history. Over and over, these women advocate for the continued oppression of Black men: of lynching, of owned bodies, of men as property and not as citizens of this land. Their faces bear no trace of the trauma and violence they have been able to wield, condemning others as they seek to free themselves.

It hits like a train: here are five women who went down as trailblazers, beloved by a revisionist history, exposed for the bigots they are. The lace is a delicate touch that goes a very long way—in the act of removing this supposedly pure, demure veil, the viewer must ask themselves where they fall on these statements. Are they, too, complicit in upholding structures of oppression? Or do they seek to tear the veils from the images, and then tear down the figures in the images themselves?

Up the hallway, Brooke Sheldon’s Hi, My Name Is Mary takes on not just that legacy, but the concept of divinity itself. In the piece, the Virgin Mary looks right out at the viewer, her eyes locked with whomever is right in front of her. A halo, flat and ribbed as a gold plate, sprouts behind her. Folds of blue and white fabric drape her shoulders and chest; the habit comes up over her cheeks and forehead. But where her mouth is—rosy, if we are to take anything from centuries of art history—there are layers of white packing tape, plastered over it in an oblong X shape.

On a label accompanying the work, Sheldon makes clear that the piece is not meant to be purely profane: she describes herself as struggling with her own lifelong Catholicism. And so, as we stare at this silenced and holy and very mortal woman, we struggle with the church right along with her. Sheldon’s work compels us to ask: for whom is this a figure of solace, and for whom is it one of pain? When was she silenced, and by what forces? That son of hers, where is he now?

Further into the exhibition, a number of surprising, sometimes viscerally moving pieces bring the theme home. Jennifer Rae's Veracious, in the back hallway, is literally meant to bring the viewer to their knees. Beneath a framed, gilded portrait with a space cut out for Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, a small stool with crushed red velvet sits ready for the viewer with a benediction. Only once the viewer is kneeling do the words become visible—accompanied by a series of data points about the newest, more conservative, majority Catholic Supreme Court of the United States.

| Detail of Jennifer Rae's Veracious. |

May your bravery be contagious, its five stanzas begin.

And your example continue to guide us.

Help us bear our trials with honor,

And have the courage to be vulnerable.

At the end of that hallway, Susan Clinard’s Surviving Sexual Trauma: The Shedding and Shelving of Memory stops the viewer in their tracks. Or, at least, it should. There’s a lot going on around it: a whole collaged body takes up a section of wall across the hall, a terra cotta clitoris and armored pair of breasts wink out from the next room.

But Clinard’s figure is breathless and urgent in her quiet suffering. In her left hand, she holds a little mummy-like white doll, small and soft like several other figures she has already made. With her right, she touches the clean arc of her back, just to make sure she's still there. There are strainers filled with foam where her breasts and uterus should be.

On a nearby shelf, there are the compartments of her memory for all of us to see—shed skin, thoughts wrapped in string and hung by their feet, white tulle that peeks out from where it has been stored. A long, skinny black tangle looks like it could be a necklace or a set of tiny entrails. We are bearing witness to this woman's pain and her recovery, and it is terrifying.

"The viewer is not just you, it is all of us, as we awaken from our toxic slumber of institutional masochistic and patriarchal behavior, as both women and boys step up to speak the truth about surviving their sexual trauma" reads an accompanying label. "She asks us to see her and acknowledge her story ... our story."

It conjures not only a palpable, thrumming sense of fear, but also an absence of self that feels intimately, horribly familiar and hollow at the same time. Our hearts clench as this woman looks over her shoulder with wide, panicked eyes, because we have been there. At least, many of us have been there.

Indeed, we want to breathe and process and vent. But we’re scared, too. What if we open our mouths, and nothing comes out? Or the words do come, and nobody else hears anything at all?