Culture & Community | Downtown | LGBTQ | Arts & Culture | Arts & Anti-racism

Top: Alyssa-Marie Cajigas Rivera Ortiz celebrating Marsha P. Johnson's birthday a week early. Bottom: TJ with Erycka Ortiz (seated) and Adrian Huq (in the pink top). Lucy Gellman Photos.

It was the impromptu circle of chairs that transformed the room, bringing the space to a momentary hush before the hum of conversation rose again. The lights came down, smiles still visible in the half-light. Bass pounded through the floor. With the wisdom of a house mother, Erycka Ortiz gave a single, knowing nod. Something sacred crackled through the air.

Suddenly, TJ was in the center of the circle, his hands a coordinated ballet as he dropped into a crouch, and began to vogue. Around the circle, half a dozen young voices came instantly to life, with jubilant cries of “Yaaaas!” and “You better werk!”

Last week, Ballroom came to Chapel Street during the sixth annual Black and Brown Queer Camp, as high school and college students gathered at the Black and Brown Power Center in downtown New Haven to celebrate and amplify long-overlooked LGBTQ+ voices. Organized by The Children of Marsha P. Johnson (CMPJ), this year’s week-long program included hours of LGBTQ+ history, a crash course in movement as resistance, frequent reminders to rest, and organizing strategies for New Haven and Connecticut.

Among campers are longtime youth organizers, teenage abolitionists and socialist scholars, and LGBTQ+ students who have long been searching for a safe space to call their own (for the first time this year, the cohort also included two puppies, Brooklyn and Mila). Last Thursday, an old-school overnight “lock in” at the center focused on rest and self-care as a form of self-preservation, in a country that is increasingly hostile toward LGBTQ+ people.

Taylin Santiago and Erycka Ortiz.

“It’s been a really, really beautiful collection of thought, of theory, of feeling,” said Ortiz, who serves as CMPJ’s co-executive director alongside Alyssa-Marie Cajigas Rivera Ortiz. “We’re thinking about how we’re challenging leadership, and if an agenda doesn’t work, what it looks like to make a new one.”

While the camp has taken many forms over the past six years, during which it has traveled from the New Haven Pride Center to Bregamos Community Theater to City-Wide Youth Coalition, its focus on LGBTQ+ resistance has remained the same. Students learn history, discuss theory, practice and terminology, dance it out, and get time to simply exist with other queer people their age. This year, Ortiz said, the level of need among queer youth was clear: she and Rivera Ortiz received applications from as far as Florida, for which they didn’t have capacity.

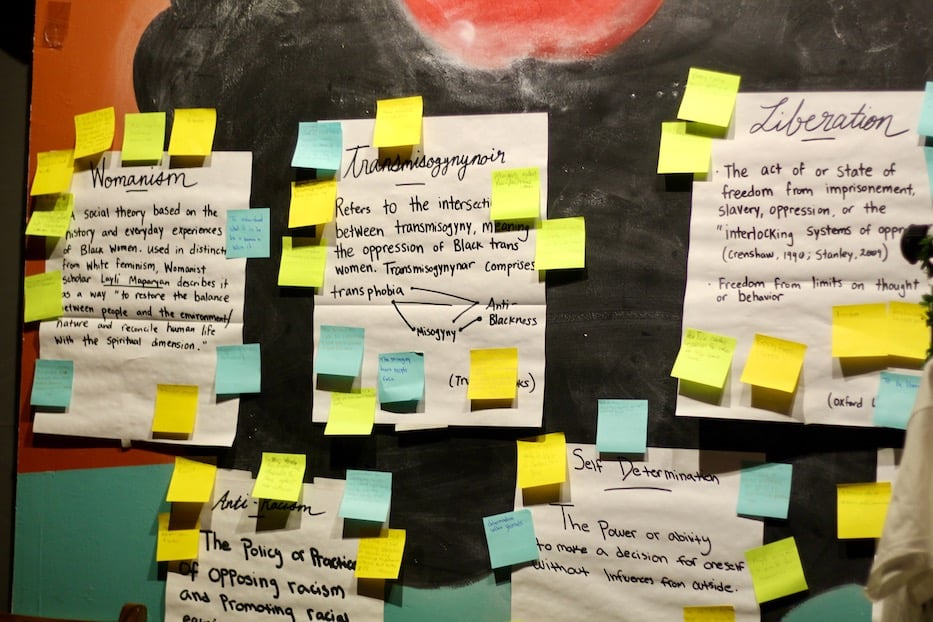

“It’s just been beautiful,” Ortiz said, motioning around the Black and Brown Power Center last week. Close to her hand, large sheets of paper covered a mural by the artist Isaac Bloodworth, her tidy cursive scrawl blooming across each. On one, Ortiz had asked campers to respond to the term “Transmisogynoir.” On another, she’d defined “Womanism.” A third read “Liberation,” with a nod to the scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw and a smattering of post-it notes from students.

It’s not all meant to feel like work, she added—and often, it doesn’t. At the center of the room last Thursday evening, Harmony Davis Cruz-Bustamante held court, a card from “Urban Trivia” perched delicately in their hand. Around them, half a dozen campers nibbled on mac and cheese, fried fish, chicken and potato salad from Sandra’s Next Generation, giggling as they split into teams, and puzzled over pop culture from Insecure to music from the 1990s.

Hours before, the dinner table had been set with a lavender tablecloth, matching purple-rimmed plates and chargers, and plastic champagne flutes that were now full of soda and seltzer. Cruz-Bustamante, who is a rising senior at Wilbur Cross High School and a student member of the city’s Board of Education, leaned back in their chair, chewing thoughtfully as they lifted another card. A fabric flower bloomed vibrantly behind their ear, as if it was listening.

“In the movie Drumline, what is the last rule in the rulebook?” they asked. A smile teased at the edges of their mouth. Before they had even finished going through the multiple choice, Andrea Kitchen-Walker scrunched her face and then smiled slyly, one hand hitting the table with a clean slap.

Harmony Davis Cruz-Bustamante (at center): Joy without inhibition.

“Shave your head!” Kitchen-Walker said before any of the other campers could get a word in. Cruz-Bustamante checked the card and declared her on an official winning streak.

In between trivia, Cruz-Bustamante reflected on three years of attending Queer Camp. For them, the camp is a chance to regroup and destress before the school year. Last year, they struggled in school, they said—not specifically because it was hard, but because it felt “boring and stagnant.” Paired with summer classes at Yale, camp was a place where they felt like they could come just as they were, and jump into a balance of rest and critical thinking.

“This year has been a lot,” Cruz-Bustamante said. “Being in this queer, Black and Brown diasporic space … it’s fun. It’s a simple place for learning and joy. Like, joy without inhibition. In the outside world, you may police the way you talk or present yourself and in here you can let yourself go.”

“I definitely feel more confident, and it’s only because I have this community to wrap around me,” they added, reflecting on the transition they’ve made from camper to facilitator, and shy high school freshman to outspoken member of the city’s Board of Education. “There’s just too little life to be hiding.”

Soul and Adrian Huq.

Every so often, passing cars and dirtbikes would send up bright, loud reminders of the outside world as they revved and trundled by on Chapel Street. Flags for Puerto Rican, Black, and LGBTQ+ Pride and liberation, installed years ago in the place of curtains, stretched over the windows, turning the light low and dramatic. It wasn’t even 9 p.m. yet—early, by campers’ standards—and already it felt like the coolest place any of them could be spending a night away from home.

In another corner, Queer Camp alumni Frenchi Rivera and Jamila Washington chatted with TJ, a rising junior at Amistad Achievement First High School. For both of them, the camp has been a safe and even familial space for years. Now, they’re trying to pass that on to students who are still navigating high school.

Rivera, who graduated from Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School in 2021, had returned to the camp the day before to teach Bomba, a Puerto Rican form of dance that has its roots in resistance and the Afro-Caribbean slave trade. After starting lessons with Movimiento Cultural Afro-Continental in 2017 (she now dances with Proyecto Cimarrón), she has become confident enough to teach in spaces like City-Wide Youth Coalition and Queer Camp.

“I love the dancing, I love the music, I love the history,” she said. “It’s like, taking a very loved piece of myself and bringing it into the community. It’s an invitation. Whatever you’re feeling, you can bring it into the batey and let it out. For me personally, I have a hard time emotionally navigating my feelings. [In Bomba,] no one has to know what I’m feeling—I just put it out on the floor.”

Helios Bergos and Mariah Roque.

She was delighted to see Bomba taught alongside the history of Ballroom, she added—both use expressive, coordinated movement, call-and-response, and a history of oppression to tap into collective care and resistance. In Puerto Rico, Bomba grew out of the Afro-Caribbean slave trade, when enslaved people needed a way to get messages to each other without tipping off their oppressors.

Centuries later, underground ballroom culture sprang up in New York, harnessing movement as a form of mutual aid, solidarity and community building in the last decades of the 20th century. When she teaches, Rivera said, she thinks of both of those histories, and the safe space that the camp has created for young people to learn about both.

When she first found Black and Brown Queer Camp four or five years ago, “it was a way for me to explore myself” before she’d come out at home, and was still worried about what her family might think of it. “It was safe. Nobody could judge me.”

In the years since, she’s felt confident enough to come out to her family, and learned that she has other queer family members to whom she can relate. TJ, who grew up between New Haven and Bridgeport, called it a model from which he’s learning. Last year, he heard about the camp through Rivera Ortiz, and immediately found that it was a safe haven.

“I grew up around violence,” TJ said—including homophobia and transphobia that came from within the household and at school—“and I don’t want anyone else to grow up in those situations.”

“It’s the freedom to express myself. The kindness. The things provided for it make me feel less insecure about myself,” TJ said. “I really appreciate it.”

As if on cue, Rivera Ortiz unboxed a cake, her hands careful as they navigated the packaging. Between her feet, a friend’s puppy, Brooklyn, ran in circles, made goofy from the smell of cream and burnt sugar. Delicately, Rivera Ortiz lowered a pink candle in the shape of the number six in the middle of the cake. She surrounded it with sparklers, the light setting her whole face aglow.

This August marks the sixth anniversary of queer camp, she said—and six years of personal and professional growth that have made her into a stronger organizer and outspoken advocate of LGBTQ+ and particularly trans rights for Black and Brown people in the state. She noted that she owes that to both her mentors in New Haven, who have ranged from Addys Castillo and Camelle Scott to Juancarlos Soto, and to mothers of the movement like Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, who would have turned 78 years old on August 24.

In 1969, Johnson made history as one of the most prominent and vocal activists at the Stonewall Inn, where a police raid escalated into a riot. During her lifetime, she advocated persistently for trans rights, opened a house for homeless LGBTQ+ youth in the 1970s, and became a strong voice in ACT UP activism around HIV and AIDS awareness in the 1980s and early 1990s.

In 1969, Johnson made history as one of the most prominent and vocal activists at the Stonewall Inn, where a police raid escalated into a riot. During her lifetime, she advocated persistently for trans rights, opened a house for homeless LGBTQ+ youth in the 1970s, and became a strong voice in ACT UP activism around HIV and AIDS awareness in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Thirty-one years ago this summer, her body was discovered in the Hudson River, in what New York police originally ruled a suicide and her friends insisted had been an act of anti-trans violence. She was only 46 years old, and full of life.

As the candles flickered and danced in blue and orange inside the low-lit center off Chapel Street, the room began to speak her memory aloud. In the corner, white-and-purple t-shirts with her name seemed to come alive for a moment, with three lavender flowers that recalled the wreaths she used to wear in her hair. The chorus of happy birthday undulated over the room.

“The children!” Ortiz called out. She soon added a clap.

“Of Marsha!” campers called back in unison, the call-and-response nearly musical.

“The children!” Rivera Ortiz joined the chorus, her voice sailing through the air.

“Of Marsha!” it was now a prayer, carried heavenward.

Rising Metropolitan Business Academy junior Adina Wali (Mila is in her lap), who said she gravitated toward the camp because it feels “like a safe space.”

Campers, it seemed, could feel the shift in the air: Marsha was there, and it made the room electric. TJ began to rearrange the chairs that sat in one corner of the room. Within moments, someone had flipped on the soundtrack to Pose. Mariah Roque took the floor, arms extended as their hands flexed at the wrists, and became instruments entirely of their own. They stepped forward into a chest pop, and the room purred back approvingly.

With no words at all, they stepped back, and TJ stepped forward, the blue of his polo soft in the low light. Roque, a rising senior at Emmett O'Brien Technical High School, looked on, completely delighted. A year or so ago, they started to learn voguing and ballroom on TikTok, but hadn’t done it outside their home until last week. The style—and the history—gives them a space to explore the breath of queer identity.

“I feel very empowered,” they half-shouted over the pulsing beat.

Top: Roque. Bottom: Heaux Bag Founder Arvia Walker.

As they danced, Rivera Ortiz checked the time: the night was young, and she had one more surprise up her sleeve before campers settled into a late-night screening of Strut or Paris Is Burning. Somewhere on Chapel Street, a car door slammed, announcing the arrival of top-secret guest and Heaux Bag founder Arvia Walker. Rivera Ortiz pulled a pair of curtains shut, poking her head out for comedic effect as students grew quiet on the other side.

On the other side of the curtain, there was a flurry of activity, and white and orange bags appeared, each meticulously painted in vivid shapes and colors. Working with the New Haven-based artist Marsh, Walker said she was excited to gift the bags to the group, as part of a social impact mission that is baked into the brand. She praised the Wild Gifting Project for a grant that made the collaboration possible.

“Heaux is about being audacious and being unapologetically ourselves,” she said. Inviting campers to look inside the bag, she added that there was an affirmation card inside. “Put it on your altar, put it somewhere that is good for you.”

The moment felt full-circle, she later added: Heaux started two years ago this month. In the time since, it’s given Walker a place to de-stress from her day job at the National Women’s Law Center. As campers unwrapped their bags and took in Marsh’s vivid brushwork on the leather, smiles and squeals of delight echoed across the room, making it feel like all was right with the world, even for a moment.

That’s part of the hope, said Ortiz. When she and Rivera Ortiz teach ballroom, when they celebrate birthdays with frosting-smudged fingernails, when they make time for movie nights, they’re also trying to teach the young organizers they work with that they can and should exist exactly as they are. That includes making time for rest, Ortiz said.

“When you’re queer, sometimes you feel like you have to show up with perfection,” Ortiz said. “We really wanted to communicate that folks didn’t need to be in a space of perfection. It was like, let’s all fall apart together—and that’s okay.”

Rivera Ortiz agreed. Six years after walking into queer camp for the first time as an organizer and a student, she's running it. In between, she’s learned about herself, helped students brave a global pandemic, and founded an organization dedicated to trans advocacy and organizing.

“I don’t think me as a 17-year-old would think that this would exist,” she said. Sometimes, she finds herself thinking of how much bigger queer camp could be with more time and resources, and has to remind herself to slow down and savor the moment. It is amazing, she said, “to have a space to witness this growth.”