Downtown | Public art | Arts & Culture | New Haven Free Public Library | Yale University

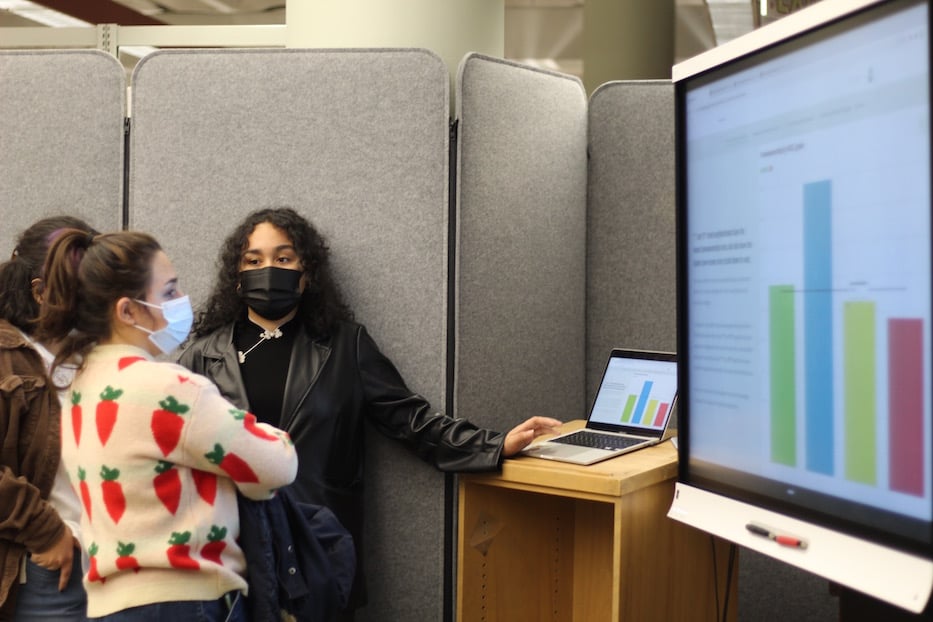

Jade Villegas, who is a sophomore at Yale, walks attendees through Memorial Mapping. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Jade Villegas scrolled to a graph on her laptop, and watched as the data points sprang to life. Three bright lines crawled across the page, tracing Covid-19 cases in Connecticut among Black, Latinae and white state residents. Together, they told the story of twin pandemics, decades of redlining and economic segregation, and an emerging effort among artists to find space to heal.

Villegas is part of “Memorial Mapping,” the second phase of a collective memory project meant to give New Haveners the room to reflect, grieve, and ultimately heal in the midst of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. From now through the end of next year, members are working towards collecting community input and securing a brownfield site in either the Hill or Fair Haven that they can transform into an interactive, evolving sculpture park dedicated to healing.

The team is run entirely by current and former Yale students, with support from the New Haven Department of Arts, Culture, and Tourism.

Last Saturday, team members and attendees gathered at the downtown branch of the New Haven Free Public Library, the first stop of a multi-branch tour to collect pandemic reflections from New Haven residents. Roughly 20 attended the event, which also included an interactive installation from Global Local Gourmet and Stir The Pot Founder Nadine Nelson and a musical performance from Thabisa. As rain started to fall steadily outside, a bright cacophony of sound filled the room.

Nelson (at right) with attendees.

“The priority is picking a place for the community that needs the most healing,” said Villegas, a sophomore at Yale University who has become the team’s head of research. “We’re just kind of giving it a platform. The issues, the concerns of New Haveners are not coincidental. It’s all by design.”

The effort has unfolded over months of research and multiple iterations of the project itself. In mid-2020, New Haven saw the first stage of the project with Design Brigade, a team of young artists, architects and designers that worked with Atelier Cho Thompson and the City of New Haven to gather early reflections from the first months of the pandemic. Then came the Diary Disk Project, an effort this summer that invited New Haveners to write their thoughts on ten huge, chalkboard-like disks distributed across the city. As the disks moved to City Hall, Design Brigadier Ye Qin Zhu stayed on to shepherd in the next phase of the project.

Villegas, who hails from Queens’ Sunnyside neighborhood, acknowledged that there’s a complexity there—an initiative run by a transient student population, particularly one attached to a university with a $42.3 billion dollar endowment, might feel suspect or extractive. Several students at the event used the phrase “for the community” rather than “with the community,” seemingly unsure of what community they were even talking about. But the Elm City also reminds her of home, a dense residential neighborhood in Queens with a population that is just larger than New Haven’s.

Photographer Roderick Topping, whose work was on display, with Joaquin Soto.

New Haven and East New York face many of the same challenges with segregation, resource allocation and food and housing insecurity, in part because the neighborhood was aggressively redlined in the 20th century. Before leaving for college, Villegas was a community organizer for years. During the summer, she now spends time teaching neighbors how to use data and statistics to fight systems of oppression, including deadly racial bias in law enforcement. At school, she’s majoring in statistics and data science to identify, call out, and counteract the way racism shows up in law enforcement, urban planning, healthcare, government and public policy.

Saturday, she and colleague Joaquin Soto scrolled through charts, graphs and flattened images of New Haven mapping the prevalence of diabetes, heart disease, asthma, food insecurity, poverty and Covid-19 in historically redlined neighborhoods (view all of them here). Villegas said that data comes largely from CT Data, DataHaven and the New Haven Department of Health.

Soto, who is the project manager for Memorial Mapping, leads the group as part of the nonprofit initiative Territorial Empathy. He grew up just blocks away from Villegas in East New York, but the two only met after arriving at Yale.

As the two traded presenting styles, photographer Roderick Topping watched intently, his eyes tracing every new shape. A resident of downtown New Haven, Topping may be best known for black-and-white photographs that chronicle a city upturned by Covid-19, from eerily empty streets to a protest around removing a statue of Christopher Columbus last year. Saturday, several of them filled the space in a mini-exhibition with Allison Minto, the photographer working on The Black New Haven Archive.

“I wanted to check all of this out,” he said. “I knew that Covid-19 disproportionately affected poor, minority communities, but to have it visualized this way is pretty revealing.”

Thabisa performing on Saturday. Drummer Sam Oliver III is pictured in the background.

Turning a corner of the library’s basement into her stage, Thabisa made the project her own. She learned about it through Zhu, a graduate of the Yale School of Art who is now an innovation fellow with the Tsai Center for Innovative Thinking at Yale. She said that its mission resonated with her—because she too grew up feeling the effects of segregation. Between Miriam Makeba covers and her hits “Diva from the River” and “Every Time,” she dipped into that history.

Raised by her grandparents in Kwazakhele, a township in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, the artist was aware of segregation everywhere she turned, she said. Back then, she didn’t know that it was called redlining and apartheid. But she could see a disparity in resources between the township and other places in Port Elizabeth. She still feels that wound open up when someone sees her and makes assumptions because she is a Black woman, or tries to shove her music into a single genre or category.

“I always wonder, what happens when we put people in boxes,” she said as Jim Lawson, Sam Oliver III and Michael Ross got into a groove behind her. “I was born into it. It’s in my DNA. I live in the trauma … that’s why this has to be a conversation that goes on and on.”

Sam Oliver III and Michael Ross.

She dipped into a stripped down, slowed version of “Imagine,” which she wrote during the International Festival of Arts & Ideas earlier this year. In their seats, attendees swayed along to the music.

“Imagine,” she sang as Oliver picked up the drumbeat behind her, and the whole room rattled to life. “This life is like a dream/You can make it whatever you want to/You can make if you try/You can make it if you believe.”

Nearby, Nelson welcomed attendees to a pop-up interactive exhibition titled Words To Eat By. On neatly arranged sheets of paper green-and-white paper, words including “Aquaculture,” “Forage,” “Food Apartheid,” “Food Sovereignty” and “Eating In Season” greeted people as they walked up to the table and took a seat.

Beside them, neat jars of dried lavender and rose buds and a bag of seashells—all materials for Nelson’s now-famous Harvest Mandalas and a natural aromatherapy station—sat waiting.

Nelson explained that food is itself inherently linked to redlining and the history of structural racism and oppression. Currently, farmers produce enough food to comfortably nourish the world, but waste hundreds of billions of tons of it each year. Nelson created the exhibition as a way to interrogate the language that people—both in the world of food and farming and outside of it—use to talk about food systems, food waste, and the way that people eat.

For instance, she said, a neighborhood may be experiencing food apartheid because of decades of racist policy making. But to call that same neighborhood food insecure without acknowledging the mutual aid efforts, community food pantries and food drives feels incomplete. As she spoke, crate of vegetables from Massaro Farm sat at the end of the table, free for the taking.

Across the table, Yale sophomore Vea Soto read through some of the Words To Eat By, nodding along to herself. She later returned to the table for Nelson’s “art activation,” which asked students to draw a meal of theirs on a black-and-white printout of a plate.

A sophomore at Yale, Soto said she jumped into the project as a way to bridge the gap between town and gown during her time at the university. Often, “it’s really easy to feel detached from the local community,” she said. As she grabbed a few markers and started sketching out vegetables, Nelson chatted with other attendees about their own culinary traditions. She later said she hoped to spur discussion around food access versus food waste.

“Anywhere that you are, there are people that are feeding each other,” Nelson said. “I think it’s important to talk about these things.”