Books | Culture & Community | Downtown | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | Literacy

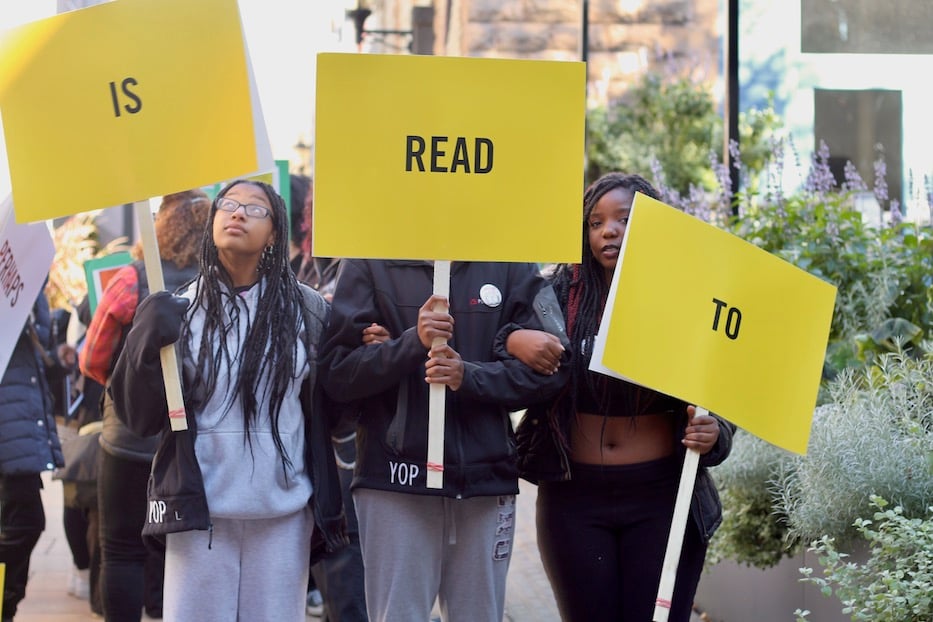

Destiny White, Erin Michaud and Jeremy Thanes. Lucy Gellman Photos.

When Jeremy Thanes picked up Mike Curato’s Flamer for the first time, he didn’t see the most-challenged book of the 2022-2023 school year. His mind didn't go to Newtown, where a school board fought bitterly over banning the book in June. Or to Westport, where a single parent tried to remove it from a high school library alongside Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer and Juno Dawson’s This Book Is Gay.

Instead, he saw himself—and the right that all young people have to be comfortable in their own skin.

Thanes, a senior at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School, brought that message to downtown New Haven Thursday afternoon, as he joined close to 100 New Haven high school students marching to protect the freedom to read. In a year that has seen a sharp rise in book bans and book challenges across the country, students showed up in force, visiting both the New Haven Free Public Library (NHFPL) and the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library before the afternoon was over. Throughout, they advocated fiercely not just for themselves, but for the generation of students directly under them, who are just starting their educational journey in New Haven.

The protest unfolded in collaboration with the advocacy group Class Action Collective, the New Haven Public Schools and the Beinecke, where the exhibition Art, Protest, and the Archives is running through Jan. 7 of next year. Participating schools included Achievement First Amistad High School, Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School, Metropolitan Business Academy, Wilbur Cross High School, High School in the Community, and Hill Regional Career High School.

“Our freedom to read is under attack in this country!” exclaimed Hovland

“That just rubs me the wrong way,” said Thames, who designed a larger-than-life cover of Flamer with Co-Op visual arts teacher Erin Michaud. The words This book will save lives scrolled in neat black lettering along the top of the poster. “It’s like someone wants to put people in a box and hide them from the world.”

From the moment students gathered at Temple Plaza Thursday, that message wove through the crowd, as students waved handmade posters and printed-out covers of banned and challenged books and chatted about their own current reads, which range from Elie Weisel’s Night to Jonathan Evison’s oft-challenged Lawn Boy. From the brightly painted steps, book jackets including The Bluest Eye, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, This Book Is Gay, and Gender Queer made an appearance, adding pops of color to the space.

In the past year, those books have been among challenges to 2,571 unique titles that the American Library Association (ALA) reported in 2022 alone. In September of this year, the ALA reported a rise in that number: groups and individuals challenged 1,915 unique titles between January and August of 2023. That’s 20 percent higher than it was a year ago at the same time.

As they held up yellow-and-black signs that read Is, Read, and To, friends Nila Lewin, Deavonah Morris and Sashaun Anderson huddled to one side, exchanging notes on the chapters of The Color of Law that they’ve been reading in a social justice class this semester. All juniors at High School in the Community, the three came out because they love to read—and are already worried that book bans will cause younger students to get an incomplete education. When their school librarian gauged their interest in the protest, it felt like a no-brainer.

“They need to stop banning books,” said Morris, adding that it concerns her that queer characters and characters of color are the most frequent targets of book challenges, particularly in children’s and young adult literature. “I think that one of the key reasons that they do it is because they don’t want kids to know their history. If this is not corrected, the generation after us will be lost.”

“Reading opens our minds!” Lewin chimed in. Anderson pointed to how instrumental reading has been in fighting white supremacy in her own life, and the lives of her peers. Without books and articles chronicling Indigenous history, for instance, she wonders if more people would still celebrate Columbus Day. For years, she’s watched it fall out of fashion, and credits access to information for helping activists move the needle.

Top: Friends Abigail Carrera and Jennifer Perez. Bottom: NHFT's Megan Fountain.

Slowly, the group became a sea of yellow-and-black, with words that bobbed over students’ heads in preparation for the action. Diminishes, read one sign, the yellow the color of an egg yolk as it hit a patch of sunlight. Enforcement, read another. Resilience, read a third. To a cheer from Class Action Collective Founder Pamela Hovland, students fell to a hush, directing their attention to the brightly painted steps where a handful of speakers stood.

“Our freedom to read is under attack in this country!” exclaimed Hovland, tracing a trend that has targeted books with LGBTQ+ characters and characters of color, as well characters who live at one or more of those intersections. “Reading and the access to ideas is our constitutional right.”

Around her, beloved New Haven bibliophiles echoed that message. NHFPL Deputy Director Luis Chavez-Brumell, who grew up in New Haven, remembered how books transported him to other universes when “school wasn’t the most fun place to be.” As a student at West Hills Elementary School, Chavez-Brumell lost himself in the pages of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings and Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s Hagakure, later learning from books and essays by James McBride, Frederick Douglass, and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Luis Chavez-Brumell: The freedom to read transported him places as a kid.

“When people are challenging those books, they’re challenging your rights,” he said, looking out over a crowd that was as diverse and polyphonic as the city itself. As a librarian who is both Black and Latino, it’s personal: he sees how people are trying to take his history, and the history of the people he works with and holds dear, off the shelves. Earlier this year, he joined colleagues and City Librarian Maria Bernhey to celebrate Banned Books Week at the main branch of the NHFPL.

That risk, others noted, extends to school libraries. Megan Fountain, education justice organizer with the New Haven Federation of Teachers, noted that in the New Haven Public Schools, the freedom to read is also an access issue. Currently, nine of New Haven’s schools have no library media specialist at all. Another 14 have a library media specialist that is only employed on a part-time basis.

The nine with no library media specialist include Celentano Biotech Health and Medical Magnet School, Dr. Reginald Mayo Early Childhood School, Elm City Montessori School, ESUMS (Engineering and Science University Magnet School), John S. Martinez Magnet School, King/Robinson Interdistrict Magnet School, Lincoln-Bassett School, Barack Obama Magnet University School, and Riverside Academy.

“What if Yale created an endowment for a full-time librarian in every school?” Fountain said aloud to cheers. On the grass of Temple Plaza, members of Amistad’s Wolfpack Dynasty Drumline looked as if they were ready to play the idea in with a rumbling beat and crash of cymbals.

Metropolitan Business Academy senior Eddie Juarez.

They didn’t have long to wait: drumline director Kjay Smith cued musicians in, and within moments they were off, marching down the narrow alleyway beside Zinc New Haven and out onto Chapel Street. As the sound floated towards the New Haven Green, students joined in, filling the sidewalk. As they made their way toward the Green, passers-by stopped on the sidewalk and street, some pulling out their phones to record.

As he crossed Chapel Street and made his way onto the Green, Metropolitan Business Academy senior Eddie Juarez lifted up a sign for Flamer, with the cover printed on one side and the publication date, number of proposed challenges and bans to the book on the other. As a person of color, he sees the attacks on the freedom to read taking place across the country—and at home in Connecticut—as both political and personal.

“It doesn’t feel good, because it’s limiting the voices that are gonna be heard throughout the world, not just in the U.S.,” he said. “It definitely makes it seem like Republicans only want the narrative that they want to push. They don’t care about other minorities, which make up over half of the country’s population.”

“I feel like especially with this new generation, it’s important to be aware of some things that other people go through, even if it’s not like, fully mainstream,” he added of why books from Flamer to Ashley Perez’ Out Of Darkness. “It’s definitely something that needs to be talked about.”

Jaylin Ambrose-Cooper and Adnan Rizal.

As they milled around the library’s front staircase, Hill Regional Career High School students Jaylin Ambrose-Cooper, Imani Bryan and Adnan Rizal all agreed. “I feel like they’re trying to limit our potential,” Bryan said. Keeping one eye on the library’s steps, they watched as peers assembled with their signs, rearranging words to build sentences.

With a drumroll before each, words went up in the air, spelling out warnings like The Freedom To Read Is Essential To Our Democracy and Enforcement Of Orthodoxy Diminishes The Resilience Of Society over Elm Street.

Standing close to the curb, Metropolitan Business Academy Librarian Charline Cupole cheered them on. A 15-year veteran at the school, Cupole has made the library into many things for Metro’s diverse student population, including a sanctuary, a study-ready refuge, and makerspace with sewing machines and art supplies, many of which come from repurposed scraps of material.

When she hears about book bans at schools across the country, “it feels like a sci-fi movie,” she said. “It just feels really sad and scary. Like … how did we get here?”

As students marched from the NHFPL to the Beinecke, Co-Op senior Destiny White joined Thanes and Michaud on the sidewalk, each of them taking the Flamer poster for a few minutes at a time. As they rounded the bend from College Street onto Wall, the reds and oranges seemed to dance, explosive as they hovered over the slate gray of the surrounding plaza.

As the drumline attracted a crowd, students watched, signs held high in the air. White, who is studying visual arts at Co-Op, said that she worries for the future of reading and literacy in New Haven and across the nation when she hears about book bans. Currently, she’s reading Jennette McCurdy’s I’m Glad My Mom Died, and doesn’t want to imagine a world where it would be snatched out of her hands.

When her mind turns to book bans, “I think it’s disgraceful!” she said.