Downtown | LGBTQ | Arts & Culture | New Haven Pride Center | Arts & Anti-racism

Ro Godwynn. "I think that part of what's giving me joy is just like, savoring my humanity," they said. "I think that so often, queer people and queer Black people particularly are conditioned to under-react to everything that happens to us to accommodate for white people and like, straight people's inability to perceive us as human."

The sound of strumming floated over the New Haven Pride Center and out through screens across the state, slipping from tiny computer speakers and earbud ports. Ro Godwynn swayed back and forth, eyes on their guitar and the camera at the same time. They spoke-sang softly over the chords, and the performance became a meditation.

"If you can hear me, go ahead and close your eyes for a second, and imagine a part of yourself that you've been told to hide. It can be anything," they said. They warned listeners that it was about to get cheesy. “Imagine that part of yourself singing this song back to you."

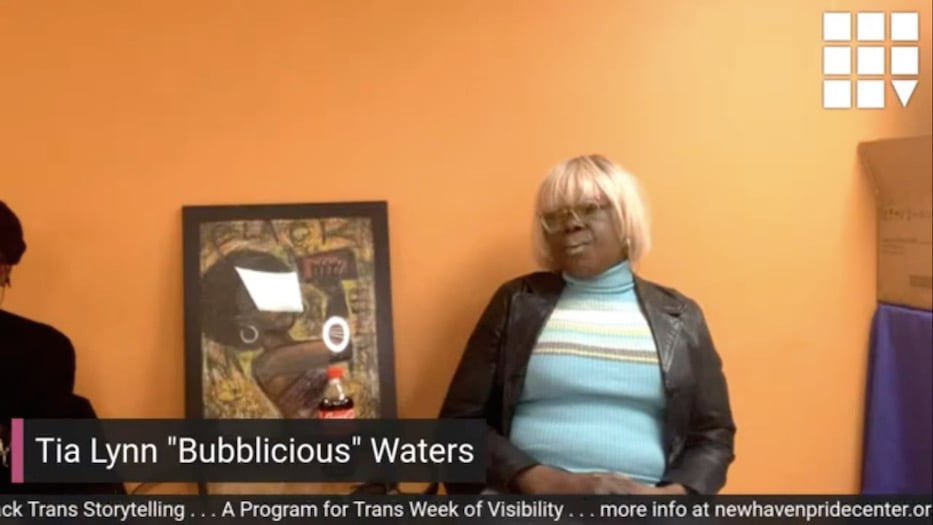

Tuesday night, Godwynn joined Tia Lynn “Bubblicious” Waters, Ty Cooper and Loren Bass-Sanford in “Black Trans Storytelling,” a program of New Haven Pride Center, BlackOut at Yale and the Yale Office of LGBTQ Resources to celebrate Trans Day of Visibility (TDOV) in an intentional affinity space. This year, the Center rolled out a mix of online and in-person events for the entire week before TDOV, which falls on Thursday March 31.

Among panels on queer spirituality, trans New Haven history, safety for New Haven’s trans and nonbinary youth and the Center’s annual “Trans Body” collaboration with Elm City Dance Collective, the 90-minute discussion centered not only Black queer and nonbinary narratives, but also the importance of joy and healing. In between stories, personal anecdotes, and a 20-minute debate on the 2022 Oscars, speakers laughed with each other, folded in gentle jokes, and encouraged each other across the virtual distance and in person.

Loren Bass-Sanford and Ty Cooper.

"This event is really just a space for Black, Trans, nonbinary, gender nonconforming Black people on the gender spectrum that are not cis to get together and share their art, stories and any creation they have related to their expression of their identity," said Bass-Sanford, a junior at Yale. A Black fist punched up through a blue, white and pink circle on their sweatshirt.

As they played Waters in, Godwynn set the tone. On screen, the the broadcast picked up viewers on Facebook and YouTube. In the center’s Orange Street home, Godwynn asked listeners to write in with what they needed in the moment. Answers filled the chat. I need love, wrote one attendee. The joy that I need... wrote the poet Sun Queen. The liberation I need, she added.

Goodwin, a self-described “Justice Queer,” wove each suggestion into the music. Everything I need/Flows like water to me, they crooned in between audience suggestions.

The lyrics—which are never quite the same, no matter how many times Godwynn performs the song—wound through the space, slipping into the side offices and clothing closet, the neatly arranged shelves of soaps and hygiene products, the stocked food pantry in the Center’s makeshift kitchen. They later rang through Godwynn’s answer on how they are finding joy in small things, from a smear of blue sky or spring wind to the perfect cup of coffee in the morning. In other words, "I'm savoring my aliveness," they said.

No sooner had Godwynn finished than stories flowed from speakers one by one, all of them candid even across the virtual space. Waters, who still performs as Bubblicious or Bubbles, recalled growing up in New Haven, with stints in Germany, the Netherlands, and New York City. In the 1990s, she was studying fashion and designing costumes for drag performers in New York City, and realized that "if they can do it, I can do it myself."

"It's very freeing when you have a dual personality that you can go to, and that's what drag was for me for a long time," she said. From New York, she returned to the city that had raised her, and became one of the most pioneering drag performers in New Haven. She is now one of the longest surviving, she said—many of the queens she first performed with have since passed on.

While she's sometimes taken aback by how little has changed—she named racism, overt and more subtle transphobia, colorism and a lack of Black drag kings and queens in the city's scene as just a few of the problems that persist—she said she's also thrilled by how much more visible queer and trans people now are. In the 1980s and 1990s, she had to take a train to a bus to find a store where she could safely shop for shoes. If she performed, she might be one of two queens in a bar. Now, she orders clothes for her drag routines online and has shared the stage with dozens of queens on a single bill.

"Back in my day, they liked your performance, but it wasn't socially the easiest thing to do and be a drag queen," she said, remembering the big-haired artsy queens, trans queens, and perfectly coiffed fashion-forward queens with whom she shared stages. "Even in the gay clubs. They liked you, but other than on stage, you were kind of like ... you can go off to the side. It was very straight-acting, because you had to hide. It wasn't as open as it is now."

In the early 2000s, she began the process of formally transitioning. Before that moment, "I felt that something's wrong with me," she said. People didn't always know how to act around her, she said, and would sometimes default to verbal or physical violence and harassment. At some point, she said, she realized that she had always been a woman—and that the rest of New Haven just hadn’t caught up.

"The one thing I've really found out is it's hard being Black," Waters said, as clean, steady snaps from Godwynn came drifting in from offscreen. "It's not easy for none of us. But it gets better as you find yourself, and you find what makes you happy. And that's what I had to do."

Decades later, Waters knows exactly who she is. As a multimedia artist, she takes inspiration from everyday life, from passers-by to the news to music she hears while walking down the street. Her work balances the bitter with the sweet, addressing themes that include police brutality, anti-trans violence, and the isolation of Covid-19, as well as the joy in design, performance, dreamscapes and intentional community that she has found in New Haven.

“Once you find yourself, you get to the age where you can tell whoever and everybody to kiss your ass and just keep movin, it’s gonna be a beautiful thing,” she said to some of the youngest attendees. “Your labels shed. You’re just yourself.”

Cooper, host of the podcast The Bussy Next Time and founder of Baldwin's Second Generation, spoke openly about the importance of creating affinity spaces by and for Black queer and trans people. A few years ago, they began working on Baldwin’s Second Generation as a place where Black LGBTQ+ voices could be in community with each other. When they started the project, they said, the work was intensely joyful. In 2019, the group was able to hold its first summit in person. "It was amazing," they recalled.

Then Covid-19 hit. In April 2020, Cooper moved a second summit online. They tried to figure out what 2021 would look like. At the same time, they watched as people started taking credit for their work, or accusing them of stealing other groups' ideas. The job that they had loved so much felt mentally exhausting. When a grant came through, it felt like a sign to move on.

"I learned that our community needs so much, and it's not my job to do everything," they said. "I cannot be everything for everyone. I cannot create space for everyone. And I was like: What can I give to my community that's holistic to me and true to me? And that brings me joy?"

The Bussy Next Time, which just released a new episode about the Marvel film franchise, grew out of the choice to shut Baldwin’s Second Generation down and find a more creative and welcoming space. Cooper urged listeners to find the joyful work in their own lives and hold fast to it. In their new podcast venture, topics that they want to take on range from a whole episode dedicated to Black men and Black masculinity to the silencing of nonbinary identities that they've experienced firsthand.

"It's still a pandemic, right?" they said. "We were in a pandemic. And I think that to expect people to continue to be working and continue to be giving 100 percent of themselves in the middle of a pandemic where people were losing their lives and dying—folks lost jobs and had to move and relocate—was a lot."

At points, the storytelling became an intergenerational back and forth, laced with laughter and quick, cheeky retorts. As Waters spoke about her career in the 1990s, she stopped and turned to Bass-Sanford and a few of the younger attendees, audible off screen.

"You weren't even here, were you?" she said, and the room dissolved into laughter. Later in the conversation, Cooper and Waters argued over the merits of Lovecraft Country, which Cooper was never able to get on board with. They pointed to the character James, a novelist who has a dog named Baldwin. It felt cheap, they said.

"I would love to debate you on some Lovecraft!" Waters said as Cooper protested. Giggles and whispers flitted in and out of the feed.

"Opinions can be wrong!" Cooper retorted. They burst out laughing, and kept the conversation going.

To learn more about the New Haven Pride Center, visit their website.