Arts & Culture | Film & Video | COVID-19 | Arts & Anti-racism

A shot from Iman Uqdah Hameen's 1987 film Unspoken Conversation. Screenshot via Zoom.

Shanti looks around the jazz club, her head swaying as she watches the other women in the room. Upright bass and drums swirl around her. There’s a burst of piano keys; her eyes widen and gleam. On stage, the drummer—who is also her husband Ted—is so absorbed in the music that he seems to have forgotten everything else.

“My story isn’t new, just untold,” a smooth voiceover announces. “So I’m telling it now, to the man whose music fills this room. These are the wives and so-called wives shattered by careless, sometimes therefore heartless, men called musicians.”

Shanti (Lisa Best) is a character in Iman Uqdah Hameen's 1987 Unspoken Conversation, a 24-minute thesis film that sharply interrogates womanhood, motherhood, and the pursuit of professional artistry. Thursday night, the New Haven filmmaker joined artist Zora Lathan for a virtual screening and conversation of the work through the Earl W. and Amanda Stafford Center for African American Media Arts at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC).

Ina Archer, media conservation and digitization specialist at the NMAAHC, moderated a post-screening talkback.

Clockwise, from top left: Ina Archer, Zora Lathan, and Iman Uqdah Hameen. Screenshot from Zoom.

The films are “making the ordinary extraordinary,” Archer said. “These joyful expressions through Zora’s films and Iman’s amazing, economical yet packed filmmaking. I’m really so pleased to be able to share a conversation with these filmmakers.”

The evening began with back-to-back screenings of Lathan and Hameen’s films, which now live in the museum’s growing collections (Hameen in the Pearl Bowser Collection and Lathan in the Great Migration Home Movie Project). In part, the collections seek to fill in gaps that persist in twentieth century Black history and storytelling, which fits into the museum's mission and work more broadly.

In Lathan’s five short films, the artist captures bite-sized, intimate vignettes of everyday life that still tap into her sense of experiment and whimsy. In American Pie, for instance, she takes a simple event—her mother and young cousin making a fruit pie together in the kitchen—and turns it into a narrative that is deeply affecting.

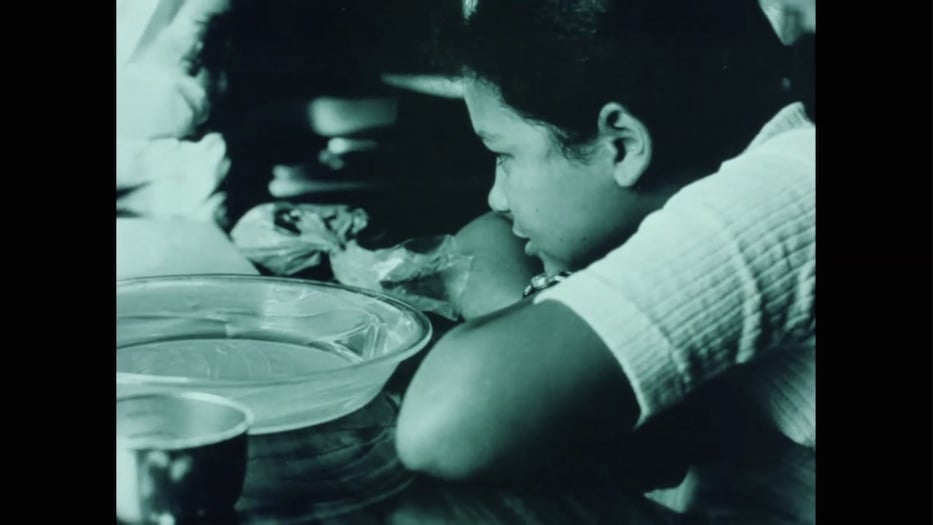

Using still images, she documents the hands that lovingly measure and mix flour and butter, prepare the fruit, roll out dough and weave a simple lattice topping. In an early shot, tints of blue and green flood the frame as her cousin stares at an empty pie dish, imagining its future. In another, thick, clear syrup pours from a bowl of softened fruit. While the exposure is in an aqua-tinted black and white, there’s a crisp, vivid quality to it, as if the characters may start moving in brilliant color at any moment.

A still from Zora Lathan's American Pie.

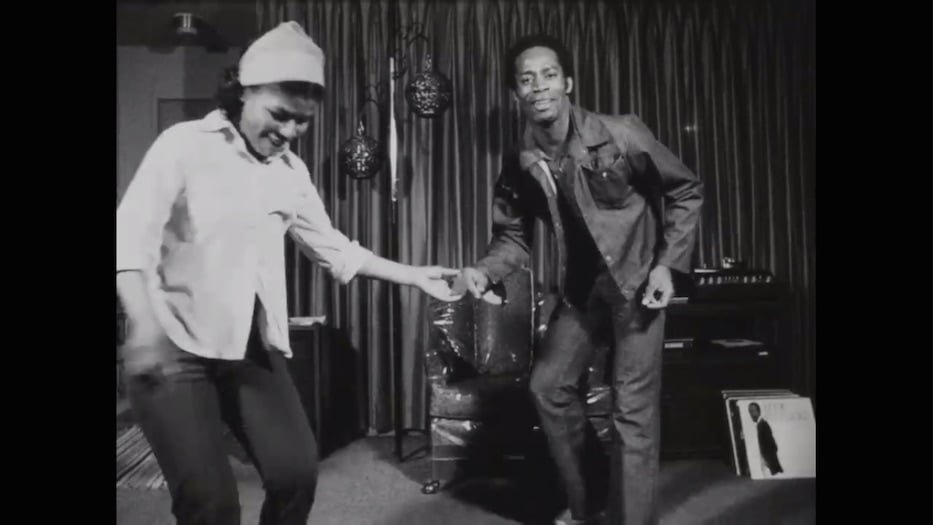

This is the story of how to make a pie, to share space, to delight in small sweetnesses and pass on a legacy. Her other experimental films—all under four minutes each—crack open that delight in the mundane. They feature members of her family, neighborhood kids, friends and her own long commute on the El. In one, her mother and cousin do the bump, speeding up suddenly as Lathan plays with shutter speed.

In another, she documents her trip to the University of Illinois-Chicago Campus with theremin and double and triple exposure, turning the film into a futuristic odyssey. Another short film, titled Aerial (1975), is ebullient as it shows neighborhood kids dancing and riding up and down the block on their bikes.

“I’ve always been very interested in the arts, but I would say I think of myself as a minor trailblazer because I always think outside of the box,” she said during a post-screening conversation.

Thursday, her films felt warm and familiar beside Hameen’s work. In Unspoken Conversation, the filmmaker tells the story of Shanti, whose husband Ted (Cedric Turner) is a virtuous jazz musician who does not see room for her talent while pursuing his. As Shanti navigates care for her two children, housework, higher education, and her own interest in filmmaking, the world pushes back at every turn. At the center is her desire to study film, which is often pushed to the bottom of the family’s list of priorities.

It is ultimately a meditation on motherhood, gendered sacrifice, and the gestation of a craft that is thoughtful and resonant today. Hameen’s real life husband, the musician Jesse Hameen II, composed an original score for the work. Her late mother, Elder Nabeela Uqdah, and children Najeeb and Hanan Hameen all appear in the film.

Hameen’s strength lies not only in the writing itself—the work is her story, put to film—but also the eye with which she directs. She is a master of both close ups and close spaces, some of which are knowingly claustrophobic. When they suddenly open up, so too—however temporarily—does her character's world of possibility.

Shanti never sees a jazz club, an apartment, a classroom in exactly the same way, and neither does Hameen. In one of the film’s most telling scenes, Shanti walks into a kitchen full of unwashed dishes, then re-pans over them as subjects. In another, she piles into the back of the family car with a drum on her lap, ready to cheer Ted on at another of his shows.

“I’m all dressed up again” Shanti says, with a tone that walks a tightrope between moxie and resignation. “I’m a queen—is this my throne? My crown, a drum on my head?”

Both point to keen-eyed reflection that still feels fresh decades later. Thursday, Hameen recalled her own path to filmmaking, which started with a love for the written word when she was a child. When the artist’s mother ran errands, Hameen would go to the public library, where “I would read and read.” She spent hours listening to the people around her, making notes in her head that she filed away for later.

"I would listen," she said. "I realized that people don’t listen."

Years later, that same fascination called her back to filmmaking. Hameen started college at Howard University on the pre-med track, inspired by her mother's work as a nurse. During those years,”I didn’t think to study film,” she said. “I didn’t even think that it was a thing.” She took time away from school, during which she converted to the Nation of Islam. Then she met filmmaker and professor Kathleen Collins at the City University of New York. The young professor, who had no patience for half-baked work or ideas that weren't fully executed, lit a spark within Hameen.

“She saw the story in me," Hameen said. “Kathy felt that all our literature, theater and film, should reflect our humanity. Nothing more, nothing less.”

Collins died in 1988, one year after Hameen finished her film as a thesis project. For decades after, Shanti’s story remained part of Hameen’s. Hameen ultimately left filmmaking to care for her family. Both she and Jesse realized that “in relationships, you compromise,” a key to a marriage that has lasted for over 40 years. Her words echoed in the midst of a pandemic that has driven close to three million women from their places of work and hit Black families, and particularly Black women, at a rate far higher than their white peers.

“Women do this, leave their stories untold, tucked away, discarded, tucked away for another time, her time,” Hameen said Thursday. “There is a sadness and a subtext where we find a man.”

A still from Zora Lathan's Experimental Cinematography Segment 1.

For Lathan, writing was also a doorway to filmmaking. As a kid, Lathan and her younger brother both wrote stories for their father, “and if he deemed it was worthy, he would give us either a nickel or a dime.” In school, she fell in love with photography before film, and then decided to major in both. She praised her parents, both interested in the arts themselves, for supporting her pursuits.

“I thought of writing as a poor person’s film format,” she said. “If you can't afford to put it on celluloid, you can afford to put it on paper.”

Both filmmakers also noted the importance of challenging a historically dominant, largely white narrative through their work. In her depictions of the universe, Lathan’s films celebrate and honor Black American life during a time when the mainstream media did not (and arguably still does not). While she “knew about Gordon Parks and Oscar Micheaux,” she didn’t have many Black creative role models growing up.

“We weren’t allowed to watch much television and I didn't start going to films as an adult,” Lathan said. “But what I did see on television, I did not particularly care for. Blacks were so marginalized, and depicted as thugs, drug dealers ... oh, especially as clowns.”

Nichelle Nichols, who was cast as Lieutenant Nyota Uhura in Star Trek in the late 1960s, may have been the exception. She fed Lathan’s steady love of science fiction, a genre where other worlds were entirely possible. Years later, Lathan did the same script-flipping with her documentary and professional work, including 12 years of environmental PSAs for the National Audubon Society. She said she does not consider her short films as home movies, so much as movies that happen to be shot in home settings.

“I am amazed, I’m thrilled. I’m honored that you found an interest in my films,” she said.

Hameen added that she sees herself and Lathan, often sidelined as “fringe,” as artists in a timeline that includes Julie Dash, Neema Barnette, and Jessie Maple. For years, she worked to get Unspoken Conversation on the radar of writer, producer and director Ava DuVernay, whose work includes highlighting filmmakers who are women and people of color. Recently, she finally did.

“I want to say, we are part of the legacy,” she said.