Culture & Community | East Rock | Justin Elicker | Citywide Youth Coalition | Elicker Administration

| Mayor Justin Elicker on his front lawn Friday evening. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

Mayor Justin Elicker campaigned on a story of two New Havens that needed to be brought together. Seven months into his first term, those different interpretations of the city emerged in an hour-long conversation on his front lawn.

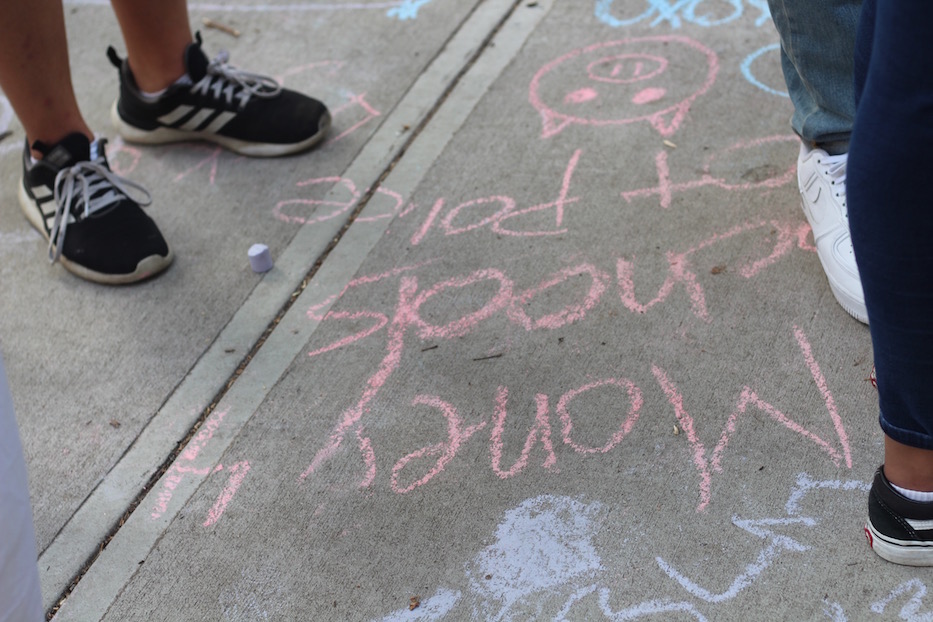

Friday afternoon, members of Citywide Youth Coalition brought their biweekly action to defund the police to Elicker’s house, located on a tree-lined section of Orange Street in the city’s East Rock neighborhood. About three dozen attended the rally, chalking up the sidewalk with messages to defund the police, protect people over property, and demand more funding from Yale University.

“A lot of us voted for you specifically because we thought we were going to get something different,” said Jahnice Cajigas, director of organizing for the group. “The truth of the matter is, I haven’t seen it. Right? I was someone who—my mom never votes. And I dragged her to the polls with me to make sure that she voted. And voted for you, at that.”

| Cajigas: “A lot of us voted for you specifically because we thought we were going to get something different.” |

In a discussion that spanned police presence, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), education funding, affordable housing, and new dirt bike and ATV legislation, two fundamentally different understandings of good governance, law enforcement and social infrastructure in New Haven emerged.

In one, changing the system involves more frequent police reports, well-oiled Internal Affairs divisions, working groups that take time, better mental health resources, and higher taxes on the suburbs, which have become strongholds of exclusionary zoning and segregation.

In the other, there’s no time to be taken. Black liberation is achievable only through defunding the police, fully funding schools, and adding affordable housing—including through the reallocation of land, financial resources, and legislative power.

Both seek the same conclusion: a world in which law enforcement is no longer necessary, because a stronger social infrastructure has rendered it obsolete. But at the core of each is a divergent view on the police itself: a body that protects, but has historic flaws and some bad officers, versus a body that is too deeply enmeshed in white supremacy to be repaired.

The conversation came on the heels of a very different discussion Wednesday night, in which an almost entirely-white crowd in Morris Cove urged Elicker to pump more money into the New Haven Police Department and increase the size of the force. It also came months after a more contentious protest on Elicker’s lawn ran into the early hours of the morning in late May.

“Let me tell you what I think our strategy is to work towards this,” Elicker said near the beginning of the discussion Friday, adding that he does not support defunding the police. “And you can criticize me, fine. Just hear me out.”

He described creating a Crisis Response Team not unlike the Eugene, Ore.-based CAHOOTS model, which prioritizes social workers, mental health professionals and medical experts over police on select calls requesting assistance.

In his view, the way to achieve it is through a comprehensive study, which takes time. Unlike the city-s ill-fated Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program, a response team would lean heavily on non-police to do work that has fallen to law enforcement.

| Recent Middlebury grad Wengel Kifle, who pointed out that landlords can be overly eager to evict Black tenants, especially Black women, during part of the discussion on affordable housing. |

Elicker urged Citywide members to trust the process—including the fact that it may take time. He outlined programs his administration has put in place to alleviate COVID-19-related food insecurity, increase internet access, and prevent ICE intervention for residents who may be undocumented, including a new “Welcoming City” order that CT Bail Fund organizer Vanesa Suarez called purely symbolic.

He noted that he was a proponent of the Civilian Review Board, which has just approved five new members, long before he was mayor. He said he believes that the police’s Internal Affairs division is doing a good job. He recalled knocking on doors and talking to neighbors in West River and Newhallville. If attendees saw trouble with the cops, he suggested, they should document it and file a police report.

“Our police officers, by and large, and you may not agree with me, are very good people,” he said. “If there’s bad conduct, if there’s inappropriate conduct, if there’s inappropriate things, we want to know about them and hold them accountable.”

Citywide member Julie Hajducky pushed back, noting that she doesn’t feel like she has time to trust the process, because it has failed people who look like her. In largely Black and Latinx neighborhoods, there’s already distrust of the police that she considers well-earned. Black people are more likely to be profiled by police, and less likely to receive due process when they are.

"We don't have time for that," she said. "This is a matter of life and death."

| Julie Hajducky: "This is a matter of life and death." |

Suarez added that it's hard to trust a process when she believes that there are racist cops on the force—including those who may still exercise force, profile Black and Latinx people, and work with ICE agents against city orders. She pointed to the recent firing of Officer Jason Santiago for excessive force, noting that the three other cops who were with him failed to stop an assault, and were not facing legal charges.

Cajigas later steered the conversation back to a list of demands that Citywide released in June, including replacing school resource officers (SROs) with guidance counselors. Schools are about to start again in the midst of a pandemic they noted. If there’s time to make the change, it’s now.

Currently, the city’s Board of Education has formed a working group to discuss the future of the officers in schools, but has not yet voted on the issue (ideally, Elicker said, there would have been a vote by now). Meanwhile, a group of former school resource officers have started a petition to stay in schools, arguing that institutions of education will be less safe without them.

Elicker said that while some students have reported harassment from school resource officers, he has also heard parents and educators push for officers who know their kids and students.

“There’s a reason that there’s committees,” Elicker said. “So that it’s not just me making a decision, right? There’s the student member of the board [referring to Lihame Arouna]. I believe Addys [Castillo] is on it. There’s a group of people that are on it. I want to hear both sides of this.”

| Remsen Welsh, who led the July 31 action at the New Haven Police Department, played a quieter support role at Friday's action. At the end of the action, she and Cajigas led the group in call-and-response chants calling for defunding the police. |

As Cajigas spoke, the two New Havens emerged again, this time in an understanding of private property, public space, and the white privilege that often separates them. Early in the evening, Elicker apologized to protesters for waiting to address them at New Haven Police Department in late May, as 1,000 protesters gathered on Union Avenue.

During that protest, several protesters were pepper sprayed by police in full riot gear. Elicker said that it was wrong—but that his house was still largely off limits. Citywide member Jamila Washington pointed out that the group had arrived at Elicker’s home Friday for one reason: “you’re not listening.”

“I'm listening,” Elicker responded. “It's not a reason to be outside my house. You can show up in front of my house. It's a sidewalk. It's a public space. But my wife didn't run for mayor. My daughters didn't run for mayor. My neighbors didn't run for mayor.”

“We don't get peace in our homes, in our communities, by your police,” Suarez responded. “Ever. Not a day. There are mothers and fathers and children being taken from their homes, and we cannot escape that. So you can be bothered one night for a few hours.”