Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | Black Lives Matter

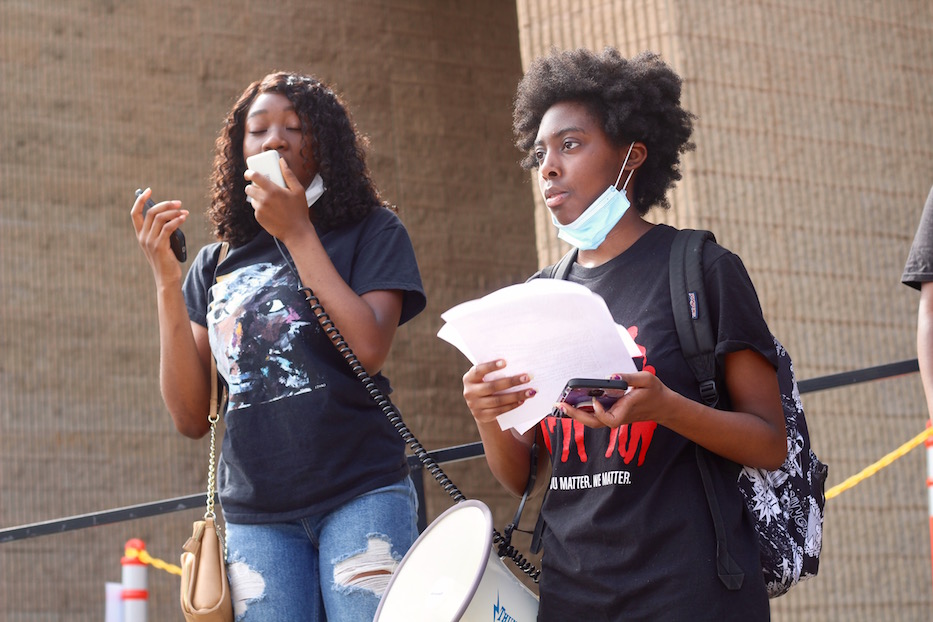

| Members of Citywide, including Remsen Welsh, Lihame Arouna, Mellody Massaquoi, Jamila Washington and Jeremy Cajigas led the march. "Thinking about people who have been brutalized by the police, or have been killed by the police and can't speak for themselves now that they've passed ... we are here to be the speakers of this movement," said Welsh at one point. Lucy Gellman Photos. |

Destin Williams remembers walking into school and feeling like there were cops breathing down her neck. Now she’s trying to make sure her peers don’t feel the same way.

Friday, Williams joined close to 20 youth organizers and 100 New Haveners for a march, rally and teach-in led by Citywide Youth Coalition and Black Lives Matter New Haven to defund the police, expand New Haven’s vision for affordable housing, and better finance public education. Citywide presented the same eight demands that it released in early June, before leading a rally that drew 5,000 people.

The demands (listen to a full list here) include moving $30 million from the police budget into the public schools, replacing school resource officers with counselors, and ending the city’s “triple occupation” by the New Haven Police Department, Yale Police Department, and Hamden Police Department. Friday, the demand to get cops out of schools took center stage.

| Jeremy Cajigas "For me, I think that it means more possibility for deescalation, more possibilities to actually provide resources for our students." |

“For me, I think that it means more possibility for deescalation, more possibilities to actually provide resources for our students,” said Jeremy Cajigas, director of organizing for Citywide Youth Coalition and a 2017 graduate of High School in the Community. “A lot of us do come to schools with issues from outside, whether it’s dealing with property and hunger, whether it’s dealing with abuse. A lot of the time, that’s what manifests itself when we’re in schools. And policing isn’t going to be what fixes or stops that. It’s what makes it even worse.”

This rally began just minutes after 3 p.m., as Gov. Ned Lamont was signing HB 6004 An Act Concerning Police Accountability (AACPA) into law in Hartford. State Sen. Gary Winfield and State Rep. Robyn Porter, both of whom represent New Haven, were vocal and fierce advocates of the bill. Back in New Haven, Citywide members gathered around the Green’s signature flagpole, chanting “Black Lives Matter” and “Take it to the streets/defund the police/no justice/no peace!”

Among the organizers were not just activists but also artists, ready to use their voices, writing skills, and work onstage to advocate for a city where schools had more money, and police had less. One of Citywide’s core principles is celebrating culture: among calls to vote, write legislators, and testify in Hartford, the group has leaned on song, dance, instrumental music and poetry to carry members through the streets and close out teach-ins from the New Havenn Green to East Rock Park.

“I think that when we talk about art and we talk about building a movement, they have to go hand in hand,” said Jamila Washington, a rising senior in choir at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School and one of the organizers of Friday’s march. “It’s a way to express yourself and to tell your truth.”

From the New Haven Green, the group wove up Church Street, cars honking as marchers fanned out across the width of the street and kept going against the flow of traffic. A few drivers pumped their fists and rolled down their windows to show support. Cars acquiesced to the group walking towards them, pulling over to curbs and stopping in the middle of the lane.

As they turned onto Union Avenue, even a 271 bus gave a staccato toot-toot of support as it waited for them to pass. Organizer Remsen Welsh, an ECA grad who is now at Oberlin College, lifted the group with another round of chants.

"Thinking about people who have been brutalized by the police, or have been killed by the police and can't speak for themselves now that they've passed ... we are here to be the speakers of this movement," she later said.

Once at the station, several attendees focused on the push to replace school resource officers with counselors and greater access to mental heath resources. The ask is a timely one: the city’s Board of Education has formed a working group to discuss the future of officers in schools, and has suggested it will have an answer by August. Meanwhile, a group of former school resource officers have started a petition to stay in schools, arguing that institutions of education will be less safe without them.

| Top: Jamila Washington and Mellody Massaquoi. Bottom: Lihame Arouna. |

“I think the narrative that this is a personal vendetta against school resource officers is completely false,” said Lihame Arouna, who is a non-voting student member on the New Haven Board of Education. “We don't hate school resource officers. But the system as a whole is not beneficial.”

“Look to every other school in Connecticut,” she added. “What does Hopkins look like? What does Choate look like? They're not subject to policing in their schools, and I think they're perfectly fine. Black and Brown students come with a set of trauma that comes with all the systems they've had to deal with. That's why, even more, they need those counselors and mental health professionals.”

Washington added her voice to that chorus, adding that she has enough to worry about when returning to school in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Among calls to defund the police, she recalled watching fellow students—almost exclusively Black and Latinx—get daily pat-downs from the SROs at her school at 6 a.m., just as the day was starting. She was one of them.

“We do understand that they [school resource officers] are human beings—that they do have jobs and they have families to feed and things like that,” she said. “But we're talking about the whole wellbeing of a whole community of people, of students going back to school. It's not the individuals that we're talking about.”

Williams, a creative writer who graduated from Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School in June, recalled learning that there was one guidance counselor for hundreds of students in her school. Meanwhile, the officers in her school made her feel unsafe, because they were “on my back, every day.”

She said that she would have preferred knowing there were more counselors available, ready to listen when she came in with a concern. Instead, there never seemed to be that "listening ear" she needed to talk to. Now that she has graduated, she plans on working for a year to help her grandmother, then attending college.

Mellody Massaquoi, who graduated with Williams, said she believes that a school without police is a safer school for students, and particularly Black and Latinx students in New Haven. She lambasted school resource officers for arresting students for getting in fights at school, when schools could be offering resources in conflict resolution and restorative justice.

“No one should have to go to school with that fear,” she said. “Without SROs in schools, you don’t have that anymore. If you invest in social workers and guidance counselors, and if students have that help in the beginning, students wouldn’t say, ‘oh, they’re bad kids.’ They’re not bad. They’re reacting to the environment that’s given to them.”