Books | Creative Writing | Hamden | Southern Connecticut State University | Arts & Culture | Arts & Anti-racism | Education

Zakiya Dalila Harris envisioned a better version of the publishing world while she was in it. So she quit and wrote a thriller with the industry’s quiet, ticking and persistent racism at its core.

Harris outlined her path to publishing Friday night, as she graced the stage at Southern Connecticut State University to discuss her debut novel, The Other Black Girl, with English Professor Brandon Hutchinson. Over 100 people attended the event, held in the university’s John Lyman Center for the Performing Arts. In a line for signed copies afterwards, they introduced themselves to each other as students, professors, dyed-in-the-wool bibliophiles and SCSU alumni who have remained sister friends for decades.

It is not her first time on campus: Harris first attended SCSU with her dad, journalism Professor Frank Harris III, when she was just a baby. Back then, she was drinking a bottle of milk from a carrier on his back. Almost three decades later, she’s now a bestselling author whose first book has defied genre, stirred in noir, mystery, and science fiction, and catalyzed discussion about whiteness and white supremacy in the workplace.

“It was surreal to have this conversation with white people in publishing,” she said Friday, beaming after an introduction as “the ah-maaaa-zing Zakiya!” from her dad. “I was like, will white people get this book? There were some who did get it.”

Harris’ book is based on her own quest for personal and professional freedom after years in the still-very-white publishing world. Born and raised in Hamden’s West Woods neighborhood, “I’ve always wanted to be a writer,” she said Friday. She grew up aware of the fact that she and her sister Aisha were two of few Black girls in their neighborhood, schools, play groups, and extracurricular activities.

Hamden played a role in her story from the beginning. At Hamden High School, she worked on the school newspaper and was transformed by a class with English teacher Gloria Chapman, a Black woman who introduced her to Octavia Butler’s Kindred. After studying at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Harris pursued a graduate degree in creative writing at The New School.

SCSU English Professor Brandon Hutchinson with Harris. Isabel Chenoweth/SCSU Photos.

The program gave her dedicated time to reflect on her experiences through writing. Harris wrote about her childhood. She wrote about her hair, including her use of relaxers for almost 15 years and decision to do the big chop after watching Stanley Nelson’s documentary about the Black Panthers. She wrote about her lived experience from Hamden to New York. It gave her space to think, she said—and a foundation for what would later become her first novel.

For three years after graduate school, she worked as an editorial assistant at Knopf Doubleday while freelancing on the side. As she rose from editorial assistant to assistant editor, she was the only Black employee in her division for years. After a promotion to assistant editor, she went to her desk and cried. Then she quit to pursue fiction writing full-time. She recalled noticing a new Black woman starting just as she departed, and finding the humor in it, as if there could only be one person of color at any point in time.

The Other Black Girl, written as she cobbled together several part-time gigs, came out of that decision to leave. So it’s not a surprise that there is a lot of Harris in her main character, Nella Rogers.

When readers meet Nella, she is an editorial assistant and the only Black employee at Wagner Books, a fictional publishing house in New York City that feels entirely plausible as Harris world builds. In her mid-twenties, Nella is sharp and ambitious—and sensitive to the micro (and macro) aggressions through which she must tiptoe, sidestep, and smooth out to survive in her workplace. She is on her own natural hair journey, a detail that later plays a central role in the book.

If she has her people outside of the office—her best friend, Malaika, and a white boyfriend named Owen—that doesn’t extend to Wagner’s chilly, cubicle-filled 13th floor. Then one day, Hazel-May McCall walks in, stepping forward in a cloud of cocoa butter to introduce herself as the newest editorial assistant. She is the titular Other Black Girl, from her “Erykah-meets-Issa” vibe to a social justice gig with students on the side.

What follows is a propulsive, bitingly funny and smart dive into their time at Wagner together. In particular, Harris does not shy away from exploring the way historical systems of oppression ask oppressed people to undercut each other. As readers get deeper into the text, she combs through a thick, intricately woven web of microaggression, KGB-level conspiracy, and magical, speculative takes on white supremacy and horror that channel Butler, N.K. Jemisin, and Grady Hendrix.

“I really wanted to make this book as thrilling and twisty as possible,” she said Friday to knowing laughter from those who had already finished the book.

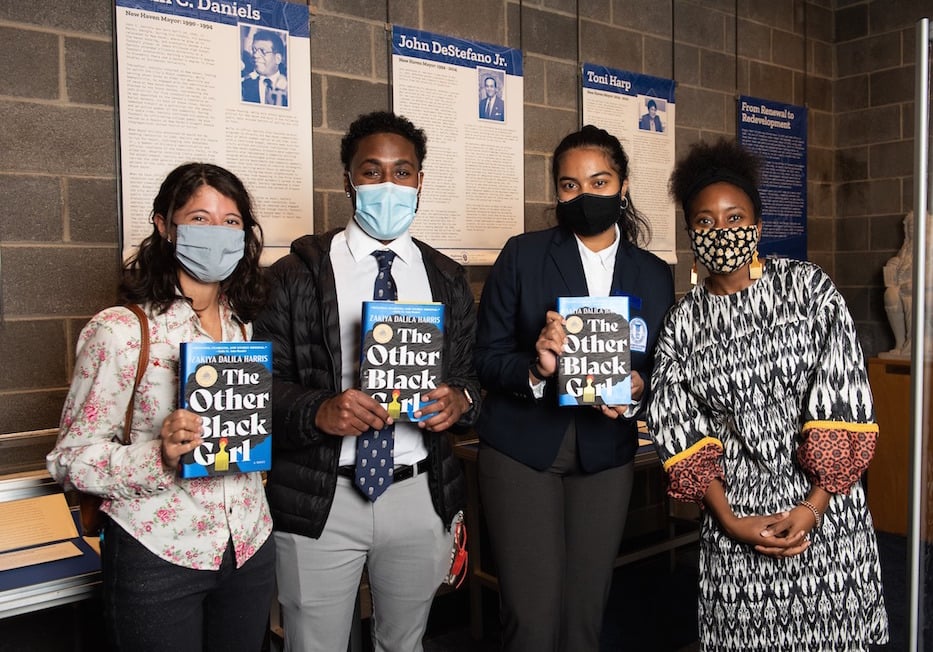

Current SCSU students with Harris. Isabel Chenoweth/SCSU Photos.

She has succeeded wildly. For any reader who has been an “only”—or experienced the treatment of an only in a workplace—there’s a painful authenticity to her writing. It’s there when Nella sits across the desk from her white boss, Vera, and must choose her words carefully or risk a dramatic, career-threatening blowout. Or when she faces a white, male author who has written a caricature of a Black woman, and sees that he is more offended by the suggestion of his racism than his actual racist behavior.

Harris has hit the nail on the head not just about publishing, but also the museum and curatorial world, the academy and nonprofit industrial complex, and the American theater among others. She undergirds her observations with an equally acute sense of humor and satire, denying readers any sort of stereotype or box for the book to fall into. In a year and change of robust lip service and very little demonstrated action around diversity and anti-racism in the workplace, it is a delicious and necessary read.

Parts of it are so real that they sting. Harris based one of the book’s most climactic scenes, which takes place between two Black women in a Wagner bathroom, after watching Philando Castile’s murder on the news and knowing she would have to walk into a part-time job at a pie shop, smile at customers, and ask them how their day was.

Friday, the author was quick to say that none of her work happens in a vacuum. Beyond her parents, who she referred to as "my first teachers," her narrative muses range from Nina Simone, Otis Redding, Diana Ross, Janet Jackson and Chaka Khan to Butler, Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin, Gillian Flynn and Stephen King. Hutchinson, who has taught Black feminist writers, the Harlem Renaissance, and American Experience and Literature among several other courses, probed her on everything from her relationship to self-disclosure to her hope for readers who pick up the book.

“What is your advice for the 'onlys' that are in the room?” she asked.

Harris, who sometimes paused and looked briefly at the ceiling as she considered an answer, didn’t miss a beat. When she was an “only” in publishing, she said, she was painfully aware of how isolating it could be for someone who looked like her. While she didn’t face explicit racism, she knew to look out for something much more subtle. That weaves itself through every section of the book, from interactions with her cubicle mates to the dinners she and Malaika have to blow off steam.

“There’s a voice. There’s a tone. There’s coded language,” Harris said. She considers herself lucky to have found allies and accomplices at Knopf during her time there. Some were white colleagues invested in doing anti-racism and work with her. Some were fellow Black women in the publishing industry who formed a slack channel and informal affinity group. What it taught her, she told the audience, was that things weren’t in her head. If people think they’re experiencing racism in the workplace, she told the audience, they probably are.

“Your feelings are valid,” she said. “If you feel comfortable saying something, do it. If you don’t,” she continued, it’s also okay to not to be the one to speak out. At a moment of intense, constant connectedness to technology, she’s still learning how to set boundaries and disconnect.

It’s one of the reasons she advocates for and lifts up other Black artists, she added. She shouted out the book jacket by Temi Coker, a Nigerian artist who is now based in Dallas, who originally created the design as a celebration of Juneteenth. She is co-writing an adaptation of the book for Hulu with Rashida Jones, which will expose it to an even wider audience.

And she’s hoping that the publishing industry—and readers—take note of the vision in the book. It's a thrilling one, but it also hints at the fact that another, very different industry is possible.

“I truly think the answer is it needs to be dismantled and rebuilt,” she said. A few cheers went up from different spots in the auditorium. The applause began immediately.

To learn more about Zakiya Dalila Harris, including where to find The Other Black Girl, visit her website.