Downtown | Giampietro Gallery | Politics | Arts & Culture | New Haven | Visual Arts

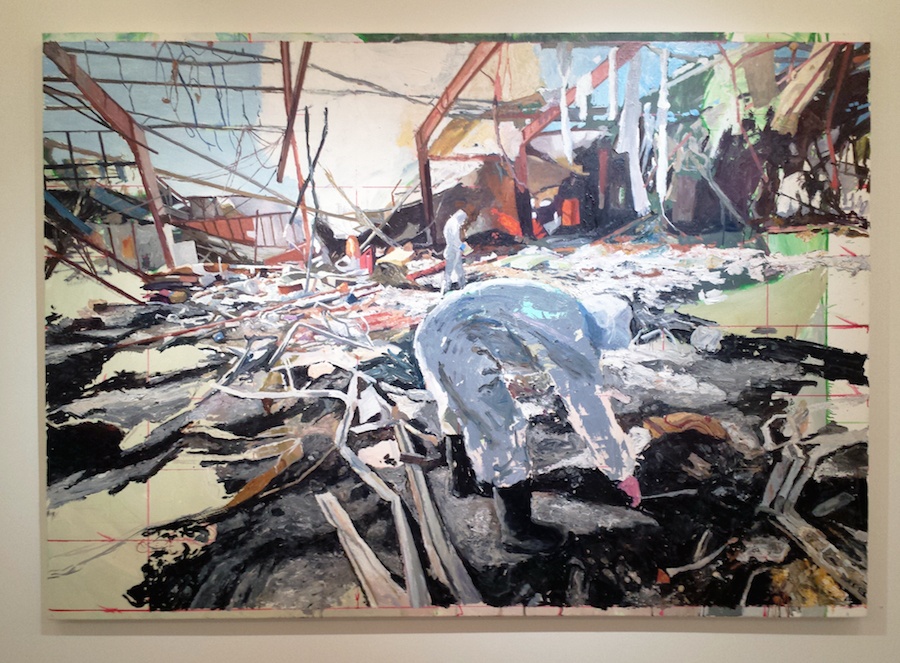

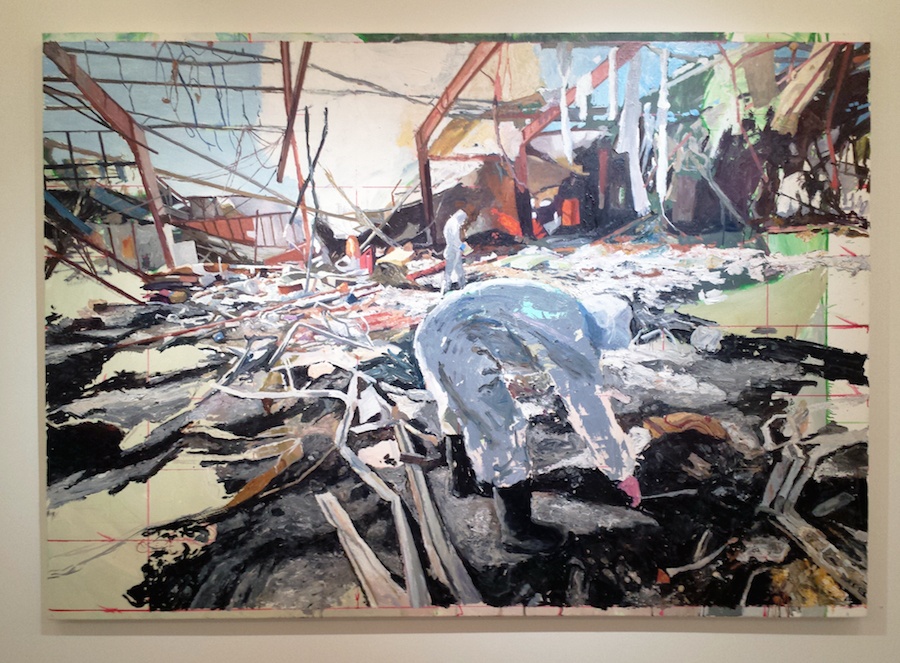

John Keefer's "Airstrike" installed at Giampietro Gallery. Stephen Urchick Photo.

John Keefer's "Airstrike" installed at Giampietro Gallery. Stephen Urchick Photo.

Giampietro Gallery’s new exhibition Aftermath starts with a bang. From the first canvas, deep, dark flecks of black paint stand out. Blast plumes roil and seethe. A clear, blue summer sky is turbulent: heavily impastoed, checked with broad brushstrokes. These clear, blue skies are rightly terrifying: they’re the skies the Americans can bomb you from.

Installed at the front of Aftermath, John Keefer’s “Airstrike” speaks to the destruction that propels the show. The image—three one-thousand pound bombs detonating in a densely populated urban area—frames Keefer’s subsequent pictures of wrecks and walking wounded. That’s also true for sculptor Kurt Steger’s blast ejecta, assemblages of wood, graphite, and found concrete.

The painting of Aftermath is disaster porn. Keefer daubs a kind of seductive, shock-and-awe smut that monumentalizes the stopping power of modern munitions at the scale of history painting. But he redeems his potentially exploitative subject matter with a meticulous, documentary style that presents the calamity of collateral damage in all its abject ugliness.

A detail from "Airstrike" Stephen Urchick Photo.

A detail from "Airstrike" Stephen Urchick Photo.

Take the multiple tenses in “Airstrike.” Keefer makes excellent use of the painter’s stock-in-trade knowledge of pigments—of colorful dirt—to precisely discriminate between the airstrike that landed an instant ago and the airstrike that splashes down now.

He defines three species of smoke. One is the sooty variety fed by open flames and shaped by convection into billowing mushroom clouds. The second is the clinging, cancerous white fog from pulverized drywall and cinderblock. And the last, a brown-beige smear of disturbed earth that’s yet to shed its delta-v and come pattering back as clods and clumps.

Keefer’s attentiveness to these details allows him to telescope the painting’s critical, unitary moment and show us a slow-motion catastrophe, a continuous bombardment that strains the nerves. The rightmost cloud landed earliest—it and its ground haze have had time to drift and shift on the wind, revealing the matte claw-shape of the ruined ground zero. The left-most column, still centered, probably developed second. The middlemost splatter has erupted within the last blink of the eye, a highly kinetic spurt.

This is neither the optics of glossy Hollywood fuel-air fireballs, nor the way of looking proposed by YouTube carnage compilations. On the one hand, it is “grittily” realistic: all frank and “dirt-y” and unapologetic. On the other hand, Keefer does not offer a sequence of violent images—arranged in some macabre supercut (they exist, in spades)—but an image of a violent sequence.

Keefer outdoes war videography that merely captures the atrocity by now commenting upon it. “Airstrike’s” viewer is asked to vacate the privileged vantage point of the Western mediasphere, characterized by its incessant barrage of readily-available images. Instead, the painting is a singular image of a barrage, an image with which the beholder is stuck and compelled to contemplate in detail. It’s a gesture towards the civilians forced to live out their lives beneath an F/A-18’s steel rain.

This human toll in “Airstrike” is a blackly comedic aside. Keefer echoes the twin towers of smoke with twin smokestacks in the far background. He creates an ironic distance (out of the physical distance) between the “legitimate,” strategic target of a power plant and outright murder.

Kurt Steger’s series of “Urban Structure” sculptures are three-dimensional koans on the difficulty of de-conflicting. Steger builds each “Urban Structure” from the same foundation—haphazardly hewn chunks of rock-studded concrete—but varies the outriding form that clings to its surface. The structures of “Urban Structure” flit across the two categories of combatant and noncombatant: evenly-planed geometries like dragon’s-teeth anti-tank barricades; sprawling trapezoidal agglomerations pierced with rectangular windows, thin-walled like a multi-story family dwelling.

Steger scores the faces of these suggestive home-shapes with long, thin, horizontal bands. It’s an effect reminiscent of New Haven’s ubiquitous cast-in-place concrete structures, like the nearby Temple St. Garage, and a fortuitous reminder that Aftermath’s bombs do not fall on ambiguous anytowns, but cities with their own, irreproducible architecture and sense of place.

Aftermath takes on the tragedy of indiscriminate warfare more directly with John Keefer’s paintings “In Sanaa” and “Pink Shirt.” In “In Sanaa,” two bunny-suited relief workers pick through bombed belongings all jumbled up like a cubist collage. Tongues of lurid red flame lick ineffectually at the building’s exposed CorTen structural members.

The workers’ forms—sheathed in coveralls—and the white linens dangling from the girders above pose difficult questions. There’s a third person missing maybe: violently undressed by blast overpressure.

The sinuous, curving white lines—unremarkable in nonobjective painting—are unsettling given “In Sanaa’s” desire to show real things. Keefer comments, tongue-in-cheek, about man’s ability to dissolve the four walls of its perspective-perfect built environment with a flick on the flight stick. Abstraction isn’t purely the painter’s prerogative: it allegedly emerged from the violence of the Great War and to violence it here returns. “In Sanaa’s” detonation blew out both the building and its picture plane. Keefer anchors the canvas along only its top margin. The entire foreground floats on an indeterminate, greenish-eggshell field.

John Keefer, "In Sanaa." Stephen Urchick Photo.

John Keefer, "In Sanaa." Stephen Urchick Photo.

“Pink Shirt’s” principle figure looks like she’s very much had the floor—her whole world—cut from underneath her, wandering into a triage from out of “In Sanaa.” The title’s yet another instance of gallows humor. The eponymous shirt, the protagonist’s face were both plastered white with aerosolized building. Deoxygenated blood mingles with the powder in a rose slurry down her shoulder, her scarf, her face.

Gloss catches under raking light, defining a shimmering, wet-looking circle of paint around the girl’s head. Blood, here, has apparently sponged into her hair (which stands out to the left in a vivid shock) and pools uncomfortably in the gap between her neck and her neckline.

Keefer’s Omran Daqneesh look-alike (“Orange Chair,” “Pink Shirt”) still hasn’t been tended to by borderless doctors. She stands and stares in a theatrical contrapposto, leaning in slightly. The beholder observes her on the cusp of speech, or—worse—as she contemplates an insane scene in the space the beholder occupies. This isn’t out of the realm of possibility: she’s only a few steps into the building; the depth of the painting is shallow and the white light of a door or screen seems near (just three silhouetted bodies away).

“Pink Shirt” here asks the question: “Who are we?” Is the viewer there to offer aid? Is the viewer part of a groaning, un-anaesthetized mass of fellow-casualties, traumatized and traumatizing to behold in equal turn? The disturbing of content of “Pink Shirt” is sure to make a few victims, to disturb and agitate. The picture directly poses the accusation that lingers in all of Aftermath’s images of death and despair; it is patently confrontational. “Pink Shirt” engulfs beholders, incorporates them into its framed drama, and outs beholders—by analogy—as true-to-life, taxpaying participants in the unbounded, unfolding misery for which Keefer’s painting is but a thumbnail sketch.

Aftermath runs Jan. 6-Feb. 3. Giampietro Gallery is free and open to the public Monday-Saturday, 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Free. For more information, call (203) 777-7760 or visit giampetrogallery.com.