NXTHVN | Arts & Culture | Arts & Anti-racism | Basketball

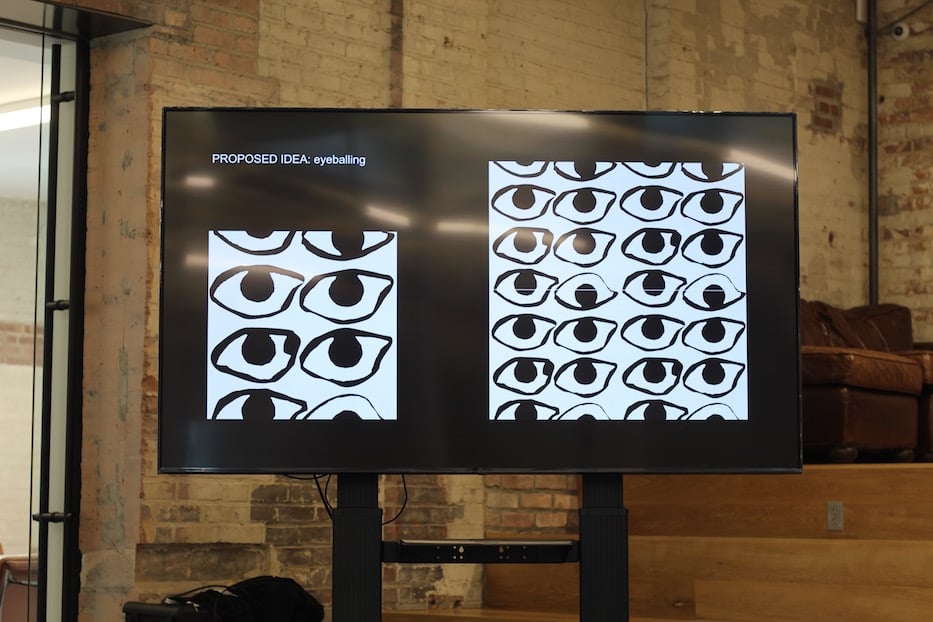

Top: Two generations of Williamsons: Kali Williamson, Brandi Marshall, Shareebah Williamson, Zanaiya "Nai" Williams and Zy’lee. Bottom: Artist Tschabalala Self's design eyeballing. Lucy Gellman Photos.

“Super” John Williamson made history when the New Jersey Nets retired his jersey in 1990. Can an artist’s new design honor his memory—and nurture another generation of basketball players—as it arrives on a New Haven court?

New Haveners asked those questions last Thursday night at NXTHVN, as artist Tschabalala Self, NXTHVN Creative Director John Dennis and several Dixwell and Newhallville neighbors discussed the proposed resurfacing and redesign of the basketball court at DeGale Field. Over an hour-long discussion, Self both presented her design eyeballing and took feedback from New Haveners, many of whom grew up or live near the park.

“We’re hoping we can push this thing through,” said Dennis, an artist and videographer who co-edited Common Practice: Basketball & Contemporary Art with Carlos Rolón and Dan Peterson. “This is a really special event and a really special project.”

Artist Tschabalala Self and NXTHVN Creative Director John Dennis. Lucy Gellman Photo.

The proposal comes from Project Backboard, which last year received a $500,000 from Five Star Basketball to resurface and add contemporary art to between 10 and 12 basketball courts across the country. After identifying New Haven as a potential location, Project Backboard Founder Daniel Peterson brought on NXTHVN as a partner. Tschabalala Self is working on the project through that affiliation.

In an email Friday morning, Peterson said that each court project normally falls between $40,000 and $60,000. He estimated that the DeGale Field project “will be under $50K.” Before work on the project begins, it must be approved by the full New Haven Board of Alders, because it is technically a gift to the city.

Dennis said that it will likely come to fruition in the first half of 2023. Watch a video of Project Backboard's full renovation approach here or at the bottom of this article.

As Dennis and Self laid out the vision for the project, New Haveners trickled in, slipping into five rows of chairs set up in a half moon in NXTHVN’s airy aula. On one side of the room, recently sworn in Beaver Hills Alder Tom Ficklin found a seat close to Push To Start founder Steve Roberts and skater Herve Locus, both artists in New Haven who have advocated for more participatory public art projects.

Kali Williamson talks with City Landscape Architect Katherine Jacobs.

In the back, Williamson’s daughters Kali and Shareebah Williamson arrived with stories of their father, who grew up in the Ashmun Street Projects, got his start playing ball at Wilbur Cross, and sailed into pro basketball history after he joined the American Basketball Association (ABA) and then the National Basketball Association (NBA) in the 1970s. The two brought a cheering section: Kali’s wife, Brandi Marshall, and Shareebah’s daughters Zy’lee and Zanaiya. As Dennis introduced the project, they hung onto every word.

Self, a graduate of the Yale School of Art who moved to New Haven in 2013, said that she’s excited to work on the court. Born and raised in West Harlem, she is now most known for large-scale collage, assemblage, and a fascination with textiles that reads as a love song to the artist Faith Ringgold and to the Black women in her family. She lauded New Haven for being a place where she could work and live as an artist after graduating.

“The city has been a big part of my narrative and I would love to be able to contribute something to the architecture of the space,” she said.

Artist Tschabalala Self's 2021 collaboration with Yoox. Lucy Gellman Photo.

As she spoke, she flipped through years of completed paintings, from her 2020 painting Sprewell and ongoing Bodega Run series to her collaborations with the fashion retailers Ugg and Yoox. A featured artist at the 2021 Performa biennial in Harlem, she zeroed in on her interest in repeated patterns, including a pink, yellow and white checker that evokes quilting squares and printed cotton.

eyeballing came out of that work. She explained that the piece is not finalized because she wants to collect and integrate community feedback before firming up the motif. Any addition of color or request for a different pattern, for instance, would come from the community. She pulled the design up on twin screens set up across the room, attendees leaning in to get a closer look.

“This is just a really preliminary idea for a design that could be of interest,” she said. “It’s a really simple eyeball motif … it could transform in any one direction. I’m really open to feedback, ideas, and concerns or questions that you might have about my work, myself.”

Malcolm Ashley: "Many eyes on what you’re doing.”

Almost immediately, community members from fellow Yale graduates and to basketball superfans hopped in to respond. Malcolm Ashley, a supporter of Project Backboard who graduated from Yale in 1981 and now lives in Atlanta, praised the artist as a trailblazer. During his time at the university, he said, he didn’t see a lot of non-Eurocentric voices coming out of Yale.

For years, the only example he could point to was artist Maya Lin, whose Women’s Table was installed on Yale’s central campus in 1993. He called eyeballing not just a chance to beautify the park, but to open a dialogue around community safety, reconciliation, and shared space at a time when an epidemic of violence is still very present. He encouraged the artist to inject “a sense of movement” into the motif, to mirror the sport to which she was paying homage.

“This is the right project and the right place,” he said. “To the point of you talking about the eye on the court, I think you’re spot on. And yes, many eyes on what you’re doing.”

Top: Kali Williamson and Brandi Marshall with their niece Zy’lee. Lucy Gellman Photo. Williamson in his prime. Photo contributed by Kali Williamson.

From the right side of the room, the Williamson sisters stood. Kali Williamson spoke, her voice growing stronger with each word. For her and for the family, she said, it is important that the project honor the legacy of her dad, a New Havener whose basketball legacy ran so deep that the Nets retired his number 23 jersey after he left the sport. He still holds Nets and NBA-wide records, she said, including points scored in a playoff game.

“He loved this community,” she said. Raised with 10 brothers and sisters in the Ashmun Street Projects, Williamson grew up going to Bethel AME Church, which sits just half a block away from DeGale Field on Goffe Street. During his time at Cross, he helped lead the team to the Connecticut state championships three years in a row. When he graduated, he soared on to college basketball, and then to the ABA and NBA. In the NBA, he set records that took years to break, Williamson said.

The city was never far from his mind, or his heart. When he retired from the NBA at 30, he moved back to New Haven, and worked with young people at a juvenile detention center. He died in 1996, when he was only 45 years old. Kali was just 19. Shareebah was 16.

The marker to Williamson, whose number 23 jersey was retired in 1990. Thursday, the family and City Landscape Architect Katherine Jacobs both visited the spot, mapped out a plan for clean up, and made time for hide and seek. Lucy Gellman Photo.

The basketball courts—used many times daily, and well-loved—are central to preserving that memory, Kali said. Two decades ago, city officials dedicated DeGale Field to her father and installed a memorial marker with his image and biography beside the court. Twenty years later, it is covered in thick lichen and a carpet of empty bottles and candy bar wrappers that litter the park.

Any design should address that problem and beautify the space in his memory, she said. She knows there’s a street named after her dad in Fair Haven, she added, but it’s not the neighborhood he loved.

“We really just wanted to make sure that he was still incorporated into whatever happens in the park,” Kali said. “He was fond of the area, his family still lives in the area … the park just really means a lot to us.”

A game unfolding last Thursday. Lucy Gellman Photo.

“He has a lot of respect in these streets and, like my sister said, we’re just trying to keep his name alive,” Shareebah chimed in, remembering how beloved her father was by youth in the neighborhood, and those he nurtured during his time working at a state juvenile detention center. “This is his area, his stomping ground … I still would like something in his community that represents him.”

Like Ashley, both she and Kali agreed that eyeballing—with the right community partners—could also double as a call to violence intervention. She pointed to the annual basketball games that Ice The Beef holds in honor of Donnell Allick, who was shot and killed in New Haven in 2011. His brother, Darrell Allick, went on to found the group, which teaches nonviolence tactics through after-school and extracurricular engagement and collaboration.

“So many things have happened over the last three years with our community in New Haven, with the world,” Kali said. “And I think the eyes tell a lot … the eyes are the window to the soul.”

“We need that oral history!” Ashley jumped back in. At the front of the room, Self didn’t miss a beat. In addition to doing her own research, she suggested generating press around Williamson’s legacy, and adding a QR code to the design or to the memorial marker at the park.

The artist catches up with community members after the discussion. Lucy Gellman Photo.

The artist catches up with community members after the discussion. Lucy Gellman Photo.

In recent years, Self said, she’s seen QR codes that can lead to first person interviews, video footage, or articles. In the front row, City Landscape Architect Katherine Jacobs nodded enthusiastically, her eyes bright over a mask.

Other attendees wondered if there might also be a chance to honor local sheroes in basketball history, including living NCAA legend Tracy Claxton. Ashley noted that he can’t see the eyes and not not think of Brittney Griner, a W.N.B.A. player for the Phoenix Mercury who is currently detained in Russia. The State Department—and at least half of the country—believes that her detainment is wrongful.

A lifelong New Havener and former basketball coach who now lives in Newhallville, Marshall moved the conversation back to Claxton, whose likeness lives beside Williamson’s in a 2009 mural on the old Stetson Library. She pointed to the fact that the star’s history is a living one—which means Claxton could her roses while she’s still here.

“New Haven has a lot of rich history,” she said. “This city is full of history. It just doesn’t get a chance to get told because we’ve got Mass and New York right around us, so all those guys get our clout.”

“A lot of people don’t realize what you can learn in this little town,” she added. “It’s very rich. This neighborhood, it’s old.”

Skaters Herve Locus and Steve Roberts. Roberts is the founder of Push To Start. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Skaters Herve Locus and Steve Roberts. Roberts is the founder of Push To Start. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Roberts, who grew up nearby on Gibbs Street, also advocated for a court that acknowledges the history of basketball in DeGale Field and New Haven more broadly. As a kid in up in Newhallville, he was close with three of Williamson’s boys, all age mates at Helene Grant School when he was a student there. As he got older, he discovered skateboarding and also played basketball for James Hillhouse High School from 2006 to 2009.

He remembered watching upperclassmen soar, glide, and block across the court and feeling motivated to become better at his craft. It ultimately propelled him to play in college and return to New Haven as a mentor for the next generation. Now, he wants to share that same spirit with the young people who hit the courts daily. He rattled off names, from De'Arie, Darrell and Donnell Allick to Williamson, Claxton, and Earl Kelley.

“What I appreciate and what I hope you convey with the motifs and the messages is the culture of street ball and of New Haven, to really give people a sense of that,” he said. “It’s something deeper than just basketball. It’s brotherhood.”

NXTHVN Director of Exhibitions, Dr. Kalia Brooks. "This is just the beginning. This is just the tip of the iceberg," she said. Lucy Gellman Photo.

As the conversation wound down, NXTHVN Director of Exhibitions Kalia Brooks reminded attendees that Thursday’s talk was only the first of several community discussions that she, Dennis and Project Backboard planned to have. She asked attendees to be “thought partners” with the organization as it moves into multiple phases of programming around the project.

“It’s already been rewarding,” she said. “The discussion that’s happening right now, it is really incredible and fruitful. I aim for it to be productive in terms of what we’re going to create together … this is just the beginning. This is just the tip of the iceberg.”

After the talk, Kali Williamson took Zy’lee by the hand, and looked down at her niece adoringly. Jacobs and Shareebah Williamson stood alongside the two; Dennis followed not far behind.

Sisters Kali and Shareebah Williamson, Zy’lee, and City Landscape Architect Katherine Jacobs. Lucy Gellman Photo.

“You wanna go see pop pop?” she asked. Zy’lee smiled. She was one and a half ice cream sandwiches into the afternoon, and had that sugared glow to her as she headed toward the park.

“Pop pop!” she exclaimed as they walked the dirt path into the park. On the courts, a game of pickup basketball was in full swing. A few yards over, Orthodox kids from the neighborhood played baseball, their tzitzit bouncing as they ran. Marshall pointed to how the park has always been a meeting place for these often separate universes.

When they got to the marker, Kali ran her finger over the letters, where lichen had grown over the surface. Jacobs reassured her: not all was lost.

“Oh, we just have to power wash it,” she said. She knelt by the marker to study any damage, then stayed to play hide and seek with Zy’lee. From the marker, a photo of Williamson—who never got to meet his grandchildren—seemed to smile a little more brightly.

To learn more about the work that goes into resurfacing a court for Project Backboard, watch the video above.