Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School | Black History Month | Dance | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | New Haven Public Schools | Theater | Arts & Anti-racism

Lucy Gellman Photos.

Tyra Geter raised one arm to the sky as Trey Songz’ “How Many More Times” filled the auditorium, and dancers moved their faces slowly heavenward. Behind her, Trayvon Martin’s sweet, smiling face appeared on the screen. His eyes were so soft. Geter lifted her whole body and swung back on one leg, then stepped forward. In front of the stage, dance teacher Nikki Claxton watched every movement, unblinking .

Geter is a student at Betsy Ross Arts Magnet School (BRAMS), where students and their teachers are dancing, playing, writing, acting, and singing their way through Black History Month. After months back in the classroom, they have harnessed their power as young artist-storytellers to share their own reflections on Black history, Black joy, and Black futures through their respective art forms.

In the process, several of them are working to open up a wider conversation based on the school’s Black History Month theme of “Dreaming Big.” Thursday night, they debuted it for the community in a virtual Black History Month assembly, their second in two years. Watch it here or at the bottom of this article.

“Everything I do, it’s from the heart—but when Black History [Month] comes, it’s a little more personal, and I try to give something back socially and something that will lift as well,” said dance instructor Nikki Claxton, a lifelong New Havener who returned to BRAMS to teach, and has never shied away from powerful and timely performances. “This one—how many more times is it gonna happen? From 1619 to Emmett Till to the present. And it’s still happening. When is it gonna stop? This is our future generation.”

One week before the assembly went live, classrooms buzzed with activity as students rehearsed. In the auditorium, dancers cycled on and offstage in black leotards, leggings and tights, eyes focused in front of them. In a sea of chairs and bleachers behind them, their classmates gathered to cheer them on. The lights dimmed, and suddenly Yolanda Adams’ “I Believe” was flying from the speakers.

On stage, students let her lyrics guide them, with a kind of easy grace and intuition that is a trademark of Claxton’s choreography. As Adams described a world that tried to hold them back, hands flew to chests, spreading over hearts in unison. Students extended their arms to their full wingspan, then looked toward the ceilings and lifted their shoulders skyward. The beat dropped, and they sprang across the stage.

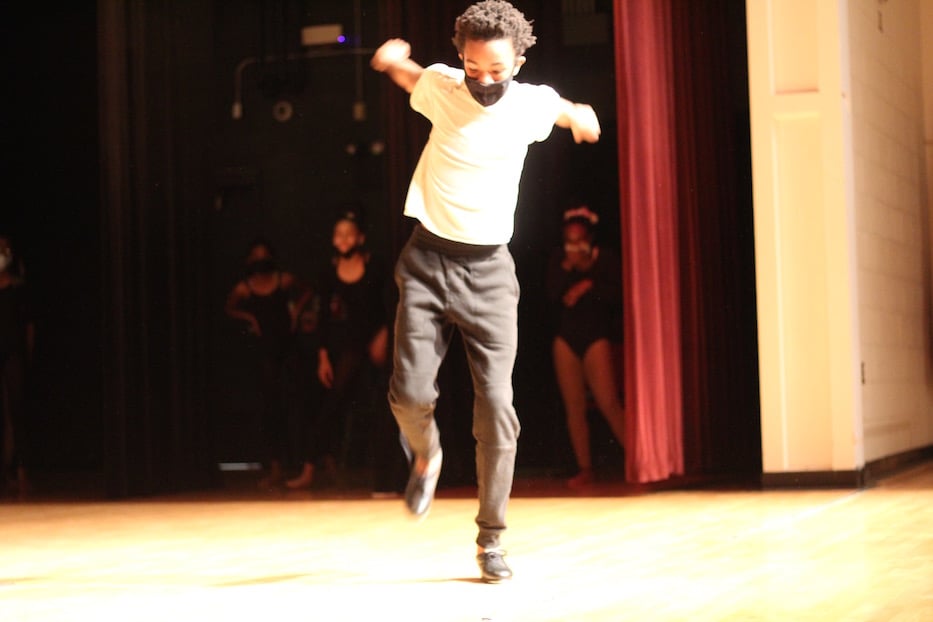

Adams belted—I believe I can! I can! I believe I will! I will!—and in the audience it was hard not to dance along. Dancers shuffled offstage, still full of movement, and the moment crackled with excitement. Then seventh grader Dakarai Langley flew out from the wings, his body a live wire.

"Non-Black people always want to put African-Americans down for the way that we look," Langley said in an interview after rehearsal. "What our dance means is you just have to believe in yourself."

As he found the right spot on the front of the stage, he melted into a tap solo, arms and legs gliding through the air as if they were weightless. His legs flew out to the sides, and he seemed totally free in his body. When his classmates flooded back onstage to join him, cheers went up from the student audience.

The work, which Claxton choreographed in dialogue with her students, is one of three that young dancers are performing to celebrate Black History as a living, breathing thing. In addition to the explosively joyful number, Hannah Healey’s students break with convention in Todrick Hall’s “Black & White,” a propulsive, poppy anthem to individuality that stars two students finding their way in a world that wants them to fall into line.

As he broke from a group of dancers, seventh grader George Villalobos spun forward and began to move to a beat that was entirely his own. Both he and fellow dancer Natalie Jambor later said that they see the song as a vital reminder to recognize and respect difference, rather than impose the violence of assimilation.

“Our dance is about accepting everyone for who they are—and I think it's really important that we do that, even now,” Jambor said. “Not just for the color of your skin, but everything … . we need to appreciate difference.”

Songz’ “How Many More Times,” meanwhile, read as an unflinching and at times very vulnerable look at the American epidemic of state-sanctioned violence on Black bodies, and specifically Black men. As the lights came down on dancers for a third time, images of Trayvon Martin, Atatiana Jefferson, George Floyd, and a baby-faced Tamir Rice appeared one by one on the screen, with still images of marchers in between.

Seven dancers began to move, every footfall deliberate. There was Elijah McClain, the gentle Colorado teenager who taught himself to play the violin. There was Malcolm, so certain of his words, and Martin Luther King, Jr. beaming tenderly at his young children. Dancers held space for Ahmaud Arbery, who was killed while running through a sun-dappled Georgia suburb. In his honor, they dance-jogged gracefully across the stage.

It could just as easily have been Stephanie Washington, who Yale and Hamden police shot and injured in 2019, or Gateway Community College student Mubarak Soulemane, who was shot and killed by a state trooper in West Haven in the first weeks of 2020. The immediacy was visceral—and for Claxton and her students, necessary.

As Songz crooned, Geter and her peers moved through the space with careful intention, their bodies rocking forward with the music. They bent back to the lyrics ‘Cause the city on fire!, and a dimpled Fred Hampton appeared, his eyes wide and glowing, as if he had been summoned. As they threw themselves into floorwork, a flurry of feet whispered from behind the curtains. They went airborne as the words “Mom, I’m Going To College”—the last words of Amadou Diallo spoke before he was killed by police—and then came back to the center, their rage elegant and heavy.

Behind them, students holding handmade signs came onto the stage. They ended stepping forward, full of might and grace, with fists raised. For a moment, it looked as if they might keep marching past the stage, out of the auditorium, and right into the heart of New Haven.

The work, in turn, is helping students dance through their feelings—and step into their own power. Last year, the Washington Post reported that law enforcement officials shot and killed 1,055 people across the country—a number that is higher than 2019 and 2020. In their classes, students at BRAMS have been learning about the Civil Rights movement, a history that is very much still with them. Geter said she is sometimes overwhelmed and exhausted thinking about the fact that protesters are still marching for the same basic human rights that thrummed through the 1960s.

Before she choreographed the numbers—one joyous, and the other heavy but hopeful—Claxton sat down with her students, played the music, spoke about the history, and opened the floor to discussion. She brought in male students from other classes to talk about how police violence disproportionately targets Black men. It’s personal to her not only as a teacher: she is also a mother, and her son is a student at BRAMS.

“All of these men were children at one point,” she said. “When do they become a threat?

When he takes the stage, eighth grader Christian Lawrence said the dance helps him feel empowered.

“If you don't have emotion while you're dancing, it's not about anything,” chimed in seventh grader Maelle Davenport. “People can feel the dance when you have feeling.”

Every time she steps on stage, Geter said, she thinks of George Floyd’s daughter growing up without her dad. She thinks about Emmett Till, and the strength that his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, mustered in the wake of her son’s senseless murder. She and fellow student Skye Williams think about the weight that Black women never asked for, and are forced to carry.

In summer 2020, Geter’s mom told her that no one would make her watch protests if she didn’t want to. She watched it anyway. “I felt like it was part of me,” she said.” While she said she feels that the country is more just under Joe Biden—a sentiment that many of her classmates echoed—she still sees Black people dying at the hands of police two years after Floyd’s murder and one after Trump left office.

"I think that's the reason why we feel it [the dance] so emotionally,” she said. “Some of us, some of our classmates, are African American. So we know the feeling of what's going on."

"I also focus on that,” Williams chimed in, standing beside her in a leotard and tights. “Since I'm a Black person, it's scary to see that. We're learning about Emmett Till. Since he was our age ... We have to be careful what we do, since we're the same race as him and stuff. We have to be cautious, and it just doesn't sit right."

“Thank God we're not in those times,” Geter said.

"Right, thank God we're not in those times, but there's still some people out here who will do stuff like that to you,” Williams responded, pointing to January 6 as a sign that racism is still alive and well. “I think about that while I'm dancing sometimes, that's how I get my feelings out. Thinking about all the deaths on the news happening, I just think of that. And it makes me mad. Racist people—they just want to take our lives for no reason."

“I Felt At Home”

Clockwise from top left: Edward Matthews Ramos, Leah Jones, Daniel Sarnelli and Christopher Lemieux. Lucy Gellman Photos.

In a drama classroom down the hall, Edward Matthews Ramos was thinking about the final touches he’d put into McFly, the trusty, bitingly funny and entirely new sidekick to a middle school adaptation of Anansi the Spider. Like the dance performances, the project is one of three new plays from the theater department in the school's virtual Black History Month assembly.

In adapting the Ashanti folktale of Anansi, which comes out of Ghana, West Africa, instructor Chris Lemieux had students in his seventh grade class read the beloved story, and improvise a staged version. He recorded and transcribed that reading—”unbeknownst to them,” he said with a mischievous glance—so he could weave their words into a final version. It worked. When he walked into rehearsal, Ramos said that “it felt like it was our story to tell."

The play, to which Lemieux added sparkly boas, neat black caps, curly wigs and outfits that are so bright white they look as though they are made of light, tells the story of Anansi, a trickster spider who weaves a web up to Nyame, goddess of the sky, in search of light to bring back down to earth. After outwitting snakes, sleeping leopards, and buzzing bees—all challenges that she has given him—he succeeds in bringing light to the world. With light comes the possibility for story.

"Sharing stories that people may not know, it's not just fun for the actors and the audience, but it's also educational at the same time," Ramos said. "If it's told the way that it's told in a textbook, you might not be able to grab little kids' attention. But if you throw that storytelling magic in there, you get their attention, they can learn—it's just a win-win. Everybody has fun, and they're learning at the same time."

For the same virtual assembly, Lemieux also directed a stage adaptation of A Computer Called Katherine, a 2019 children's book based on the life of NASA's Katherine Johnson (watch it at the bottom of this article). Drama teacher Daniel Sarnelli, a 14-year veteran of the department, worked with students on research projects based around "space explorations and the history of Black Americans involved in space."

It resulted in Rocket Manny, a short play about a young Black boy who wants to—and ultimately does—use his own research to propel himself into space on his bicycle. Along the way, his friends learn about Black trailblazers in science, physics, drama, and math, from Star Trek’s Nichelle Nichols to astronaut Guion Bluford to the astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson. In the finished performance, he drops factoids that range from science dorkery to philosophy with a poetic twist.

Filing into the room last week, Ramos and fellow seventh grader Leah Jones both said that theater has helped them contextualize not only Black History Month, but also the Covid-19 pandemic. Jones, who is interested in medicine and finance, said she can see being an actress. Ramos, who plays soccer when he’s not onstage, said that theater became his coping mechanism during the pandemic. It still is.

“Theater's like that friend that you don't exactly see all the time, but when you need them the most, they are there,” Ramos said. “Theater's always been there for me. I could work on my wacky voices when I needed to … I could just better myself as a thespian.”

During remote learning, “I missed the stage more than anything,” he added. “Finally stepping onto the stage, seeing the audience ... I felt at home."

Watch the full Black History Month Assembly, which includes performances from students in choral music, strings, dance, and drama, above.