Books | Culture & Community | Arts & Culture | Arts & Anti-racism | Possible Futures

Top, from left to right: Authors Dawn Staton-Dailey, Stacy Graham, Patricia Bellamy-Mathis, Rosamund White, and Melissa-Sue John. Bottom: Books from Lauren Simone Publishing House. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Dawn Staton-Dailey spent years finding the right words to say when kids noticed her son’s hearing aid. Usually, they were just curious, intrigued by the shell-sized piece of plastic and tubing that helped him hear. Sometimes they thought it was strange. Then a light went off in her head.

“If my friends start to stare, you tell them, That’s my bionic ear!” The words had a ring to them. She wrote them down—and then she kept writing.

Carter—who is now six, and very much a young superhero—is the protagonist in Carter and His Bionic Ear, a children’s book Staton-Dailey published last year through Imagine Her and Aspenne’s Library. Saturday, it took center stage during a Black Children’s Book Week meet-and-greet and author fair, held at Possible Futures Bookspace at 318 Edgewood Ave.

The week also included multiple read aloud sessions, held both on Zoom and at the Stetson Branch Library on Dixwell Avenue. While Black Children’s Book Week is a national event, this marked the second annual iteration in New Haven, where it centered and celebrated Black Connecticut authors.

Author Dawn Staton-Dailey.

“I think it’s something that, it really tugs at my heartstrings, to be able to share it like this,” said Staton-Dailey, who grew up in New Haven and is now raising her two sons in the city. Around her, children’s books seemed to multiply, from Aspenne Colors the Neighborhood and A Worm Named Small to I May Not Be Like You But We Could Be Friends. Nearby, Carter sat in a gray sweatshirt, sinking into the deep couch cushions as he savored his Saturday morning.

Born last year in New Jersey, Black Children’s Book Week is the brainchild of author Veronica Chapman, who started the event as a way to increase representation in children’s literature. For Chapman, the approach is tied to research that shows Black children who see themselves reflected in books and media have higher self-esteem, socialize more easily and are less likely to be angry or depressed.

Last year, it came to New Haven through Rebekah Moore, a lifelong resident of the city who is also an educator, toddler mom, avid reader, podcaster, and the program director at the Arts Council of Greater New Haven. (In the interest of full disclosure, the Arts Paper receives support from the Arts Council of Greater New Haven but is editorially independent from it.)

Author Rosamund White and Arts Council Program Director Rebekah M. Moore.

For Moore—who was building her son’s book collection before he was even born—it was a chance to connect with Black authors from around the state, from Staton-Dailey and Darius Good to Patricia Bellamy-Mathis and Melissa-Sue John. After starting in the Arts Council’s 70 Audubon Street space last year, she said she was excited to branch out to Possible Futures and Stetson. As a parent, she’s part of the 1,000 Books Before Kindergarten, a movement to catalyze early childhood literacy.

“Who better to tell our stories than ourselves?” she said as the sun streamed through into the bookspace, light dancing across the floor and on the snugly packed shelves. Next to her, a trio of new books waited to come home with her.

Around the space, authors set up by the street-facing windows and bookshelves, excited for their littlest readers to arrive. Close to the door, author Stacy Graham laid out pastel-colored copies of A Day With My Mom, inspired by her deep love for her mom, the late Naomi Kelly, and her own time as a mother. While her mother was not able to see the final copy—Kelly passed away in May 2021, just months before the book was published—she became the foundation for both the book and Graham’s belief that she could write it.

Stacy Graham, author of A Day With My Mom.

Born and raised in the city’s Westville neighborhood, Graham “always dreamed of being a writer,” she said Saturday—but for years, life got in the way. There was her career as an educator, which has spanned over three decades at Ross Woodward Classical Studies Interdistrict Magnet School. She was also a mom herself, and a very active member of her church. And yet, she knew that there was a story inside of her.

“The first thing I had to do was believe that I could write,” she said Saturday. When Covid-19 hit New Haven in March 2020, she found herself with more time on her hands. So she wrote—and wrote, and wrote, and then wrote some more. Her words filled the silence that followed school closings, shuttered businesses and houses of worship, and online-only classes. The book poured out of her.

As she wrote, stories from her childhood materialized, blooming across the page with the help of illustrator Kavion Robinson. She credits Latoya Wakefield, an author and publisher based in Jamaica, for helping her cross the finish line. While Kelly died just months before the book was published, Graham knows her legacy lives on through the book.

“It was so exciting [to finish it],” she said, bursting into a smile as a few young readers came through the door. “I can’t believe it. When the first copy came, I cried.”

18-month-old Ruby Brown and her mom, Hamdenite Sarah Kochin.

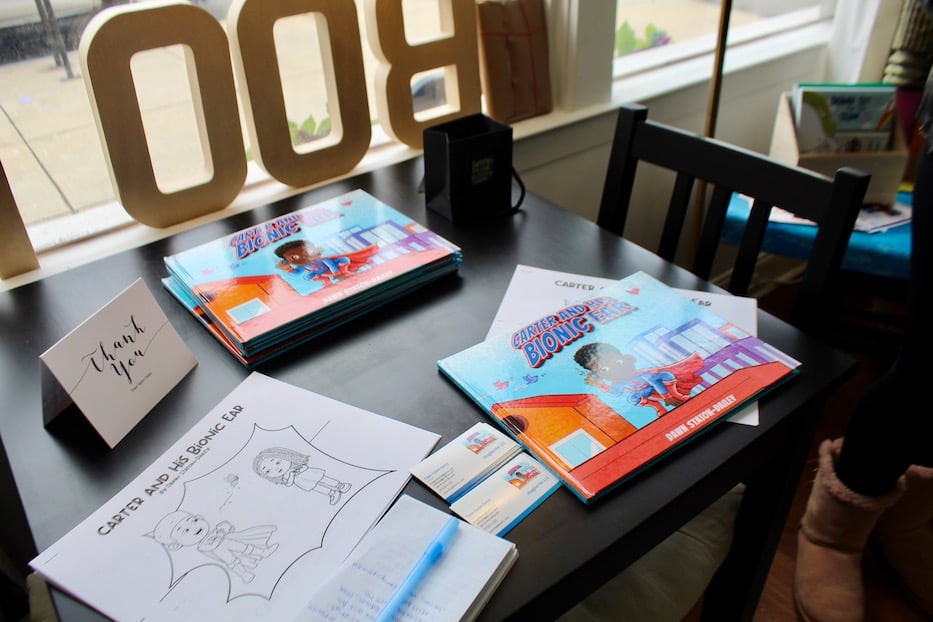

That book joy radiated across the room, jumping from A Day With My Mom to tables for Staton-Dailey, Aspenne’s Library, and Lauren Simone Publishing. Just feet from Graham, Staton-Dailey laid out signed hardcover and paperback copies of Carter and His Bionic Ear, the illustrations from Miss Monica exploding in a superhero blue-and-red on the front cover.

A lifelong New Havener, Staton-Dailey was inspired to write the book after the birth of her second son, Carter, who is now six. After she gave birth to him, Carter suffered neonatal meningitis, ultimately losing some of his ability to hear in one ear. With a background in both nursing and early childhood education, Staton-Dailey understood what doctors were telling her, and felt like she had a handle on his medical treatment.

What she didn’t always have the words for—at least initially—was telling him why it was important to wear his hearing aid. Often, kids were puzzled by it, because it was different. But without it, she knew Carter would miss out on much of the world around him. Carter And His Bionic Ear grew out of some of those conversations.

She found the time to write the book during the first year of lockdown. When she looked for a publisher, she found support from Bellamy-Mathis, a fellow Connecticut mom and author who runs Aspenne’s Library, LLC in honor of her young daughters, Aspenne and Nova.

Copies of Carter And His Bionic Ear, with which Staton-Dailey offers a coloring book.

In the book, a little boy springs out of bed, arms extended to their full wingspan. His bedroom is the bedroom of a loved, dreamy child, complete with prints of astronauts and superheroes gliding through space, their capes and costumes full of color. Before he heads to breakfast, he slips in his blue hearing aid, ready for another day.

Suddenly, he’s ready to greet the world—and it’s ready to greet him. With his bionic ear, Carter can hear everything: his brother Devin eating his cereal, hushed cell phone conversations and the bell chime of notifications, the whisper of his toothbrush and the meditative buzzing of bees as they fly low over the city sidewalk.

With his aural superpower, he imagines himself in a superhero, as if Joy the Black Boy has teamed up with Captain America after a happenstance meeting. The hearing aid is no longer a strange-looking nuisance: it’s a life-saving device, powerful enough for Carter to hear far-away protestations, kids in distress, and the mewing of cats trapped in the city street. When his classmates peek curiously at it, he explains what it does.

“When my friends ask about it or start to stare, I tell them it helps me hear sounds that I wouldn’t normally be able to hear,” Carter explains in the book. For Staton-Dailey, it’s a way to teach kids not to fear that which is different, or may at first seem strange. She called it a full-circle moment, after years writing poetry for both herself and others.

Melissa-Sue John of Lauren Simone Publishing House.

At a wing-bedecked bench beside her, Bellamy-Mathis beamed watching Staton-Dailey interact with young readers and adult ones alike. When she started Aspenne’s Library with her book Down South for the Summer, she never wanted it to just be for her. She wanted it to be part of a bigger push to amplify and support Black authors across the state.

“When I created a publishing agency, that’s what I wanted to do,” she said.

Saturday, it seemed to be working in real time. No sooner had Hamdenite Sarah Kochin entered the bookspace with her fiancé, Ryan Brown, and their 18-month-old daughter Ruby, than Aspenne Colors The Neighborhood had a new fan. As she wriggled in her mother’s arms, Ruby caught Bellamy-Mathis’ eye and grinned as a copy of the book landed in her tiny hands.

It’s an interest that Bellamy-Mathis shares with bibliophiles like Melissa-Sue John, whose East Hartford-based imprint Lauren Simone Publishing House has grown to include educational books on animal habitats, modes of transportation, global migration and cultural customs in both English and Spanish.

Recently, John said, some of those authors have felt more welcome publishing in Connecticut than in their home states of Florida and Texas, where their books may be banned from the classroom.

An excerpt of A Worm Named Small, by Janice Polite.

Since founding the publishing house in 2017, John and her authors—including her daughters—have been working to get the books into classrooms and school libraries around Connecticut. Several of them dovetail with grade-specific curricula, including a new guide to animal habitats from her daughter, Olivia Lauren.

“It’s giving back to the community,” she said, adding that she was recently tapped as a participant in Goldman Sachs’ One Million Black Women initiative.

Author Rosamund White, whose book Home, Where Is Home? celebrates her own journey from Antigua to Brooklyn to East Hartford, said that she was excited to be at the fair, and to connect with other Black authors. She added that she hopes her book resonates with all readers, no matter their background.

“If you know where you’re from, then you know where you’re gonna go, because the earth is yours,” she said. “You bring something with you to each [new] place that you live in. It’s important that children understand that we all came to America, the melting pot, to share our stories, our history, our culture.”

To learn more about Black Children’s Book Week, click here.