Co-Op High School | Creative Writing | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | Theater | COVID-19

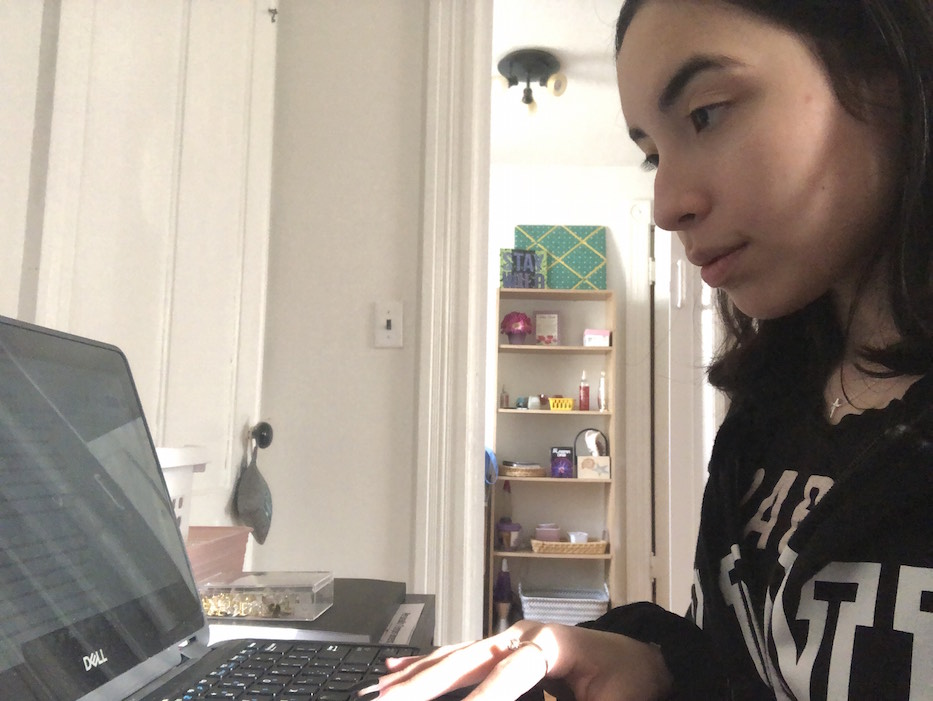

Sofia Carrillo. Photo Courtesy of Charley McAfee and Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School.

One student is using dystopian American horror as her source text. Another has imagined 13 kids trapped on a remote island, where murder is the only way out. A third tries to get into the mind of a '70s-era serial killer. All of them are using old-school letter writing—and some pandemic-era technology—to round out their junior year.

That’s the story for students at Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School, who are involved in an international play-by-mail festival called Post Theatrical. The festival, which is the brainchild of RealTime Interventions artistic directors Molly Rice and Rusty Thelin, features 13 different theater companies all using mail—often in very different ways—to communicate with their audiences.

Post Theatrical launched in February and runs through June. Co-Op’s chapter, titled Lost and Found: Coming of Age in A Pandemic, begins April 30. In its current format, audience members who buy a ticket receive one piece of mail per week, sometimes written and sometimes multimedia content, for five weeks. The final letter includes a return envelope through which they are encouraged to write back.

Co-Op is the only high school involved in the project. Tickets, which are on sale through April 30, are available here.

“We’ve had to reimagine everything,” said Charley McAfee, a Co-Op theater teacher more affectionately known as “Mr. Mac” who is supervising the project. Last year, he and his students grieved the loss of in-person theater as stages went dark and classes moved online. “So much of what we do is dependent on an atmosphere of production. But quitting isn’t an option. Waiting isn’t an option. We’ve just gotta keep creating.”

Post Theatrical was born last year, after Rice and Thelin had to do some of that reimagining themselves. RealTime Interventions, which is based in Pittsburgh, has long been interested in theater that engages and pushes notions of community. Previous shows include dives into Afghan culinary traditions, female serial killers, and site-specific theater with city residents. Before the pandemic, the two were working on re-staging Rice’s 2003 The Birth of Paper, which has an interactive component built in.

When Rice premiered the work 18 years ago, “I gave audience members little envelopes that said, ‘the world is full of paper, write to me,’” she said in a recent Zoom call. She received mail for two years, even after moving homes and setting up a forwarding address. When Covid-19 shut down stages, she and Thelin took stock of how they could keep making theater during the pandemic.

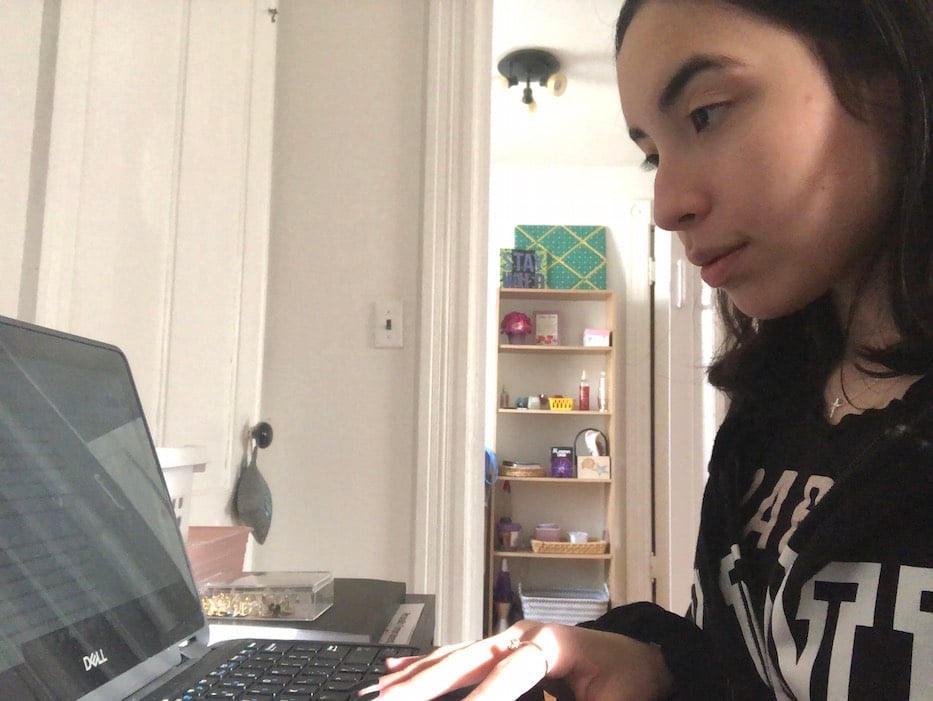

They had help: in addition to rolling out collaborative work online, the two were part of The Orchard Project’s 2020 Liveiness Lab, a virtual gathering of artists from across the country who were all grappling with the same global pandemic. By the time participants met last summer, the novelty of Zoom readings had worn off. Many were starting to realize that stages might be closed longer than anyone initially predicted. Since the lab, most venues have not yet physically reopened.

Post Theatrical Photo.

“They were trying to figure out how to use their time in the summer to talk about what liveness is outside of shared space,” Rice said. “We went into the Liveness Lab, and 150 theater folks were trying to figure out how we were going to be doing theater. We realized that we have this unique opportunity to do a national season of plays.”

Rice and Thelin started reaching out to collaborators across the country and the globe, excited by the possibilities of mail in a year that has threatened the existence of the U.S. Postal Service. Some were as far away as Lebanon, where an adaptation of The Birth of Paper will send pieces from Pittsburgh’s Handmade Arcade to recipients in Beirut in June. Others were closer to home, like New York’s Tiny Box Theater, which is working with an artist in Hong Kong. Rice connected with McAfee, who her graduate student at Point Park University. She and Thelin proposed that his students—perhaps as tired of online attempts at performance as he was—might like to return to old-school letter writing.

McAfee jumped at the idea. So did his screen-weary students. At Co-Op, he beta tested it with two junior year theater classes who sent letters to each other, to him, and to fellow Co-Op teacher Scott Meikle. He recalled getting the first dispatch from Christopher Cazarin, a junior who is working on a play where he tries to get into a serial killer’s head. Cazarin imagined the documents the killer might send to his victims. A letter, decorated to look like it was splattered with blood, arrived in McAfee’s mailbox. He was delighted.

“You’re part of a story in your own time, in your own house,” he said. “There’s a magic there that is missing from online theater.”

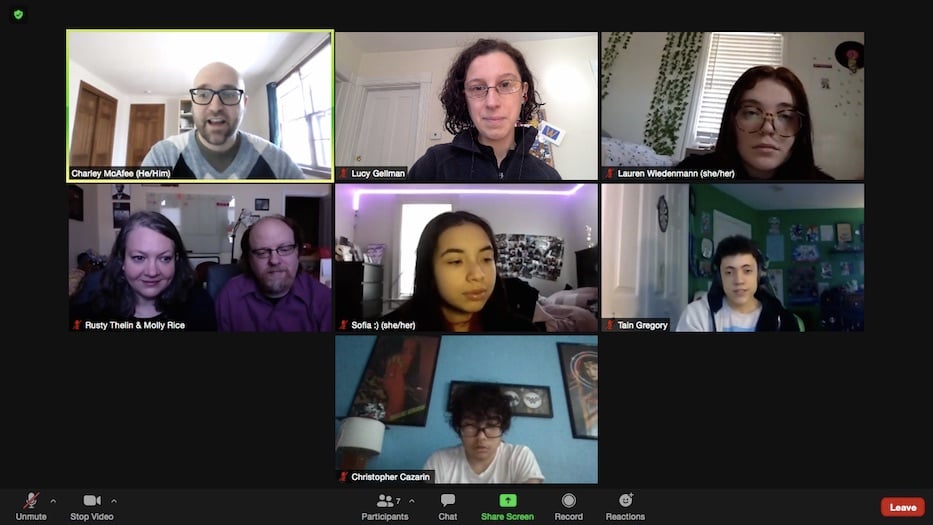

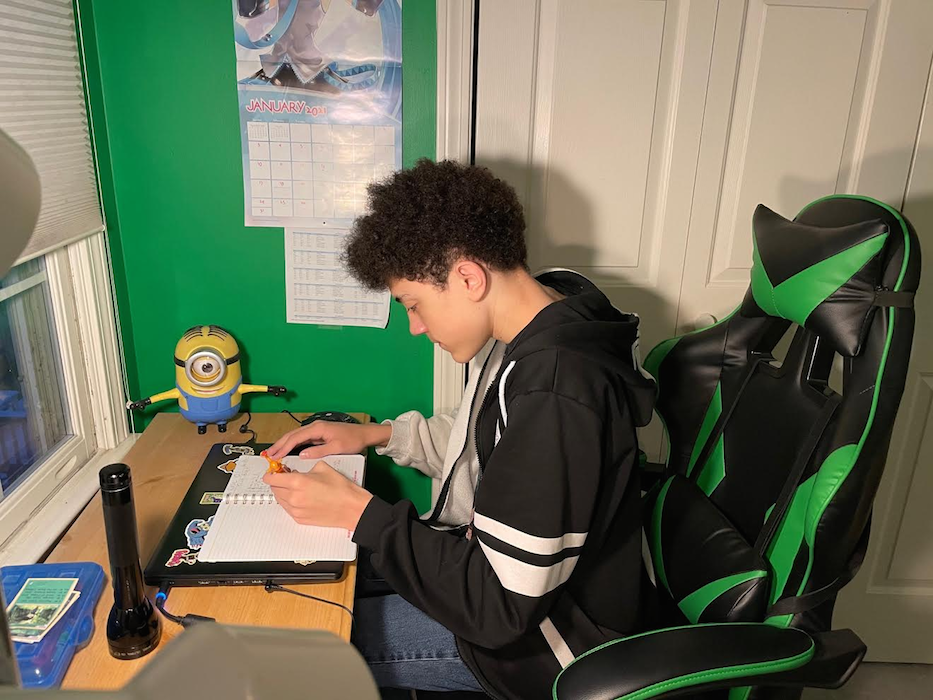

Tain Gregory at work. Photo Courtesy of Charley McAfee and Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School.

From that first attempt, Lost and Found grew into a multi-departmental, multimedia undertaking. McAfee brought in other theater students, as well as students in Co-Op’s creative writing department. Under his direction, junior Lauren Wiedenmann began building a website for the project. He gradually pulled in student artwork, from photography to drawing. Other students looked at the work they’d been doing, and got creative.

Junior Tain Gregory, for instance, was working on a 200-page play based on the Japanese video game Danganronpa. In the work, 13 kids “are trapped in an island resort, and the only way they can escape is to get away with murder,” he said. It’s a sprawling piece that grew out of an assignment for a 10-page play. When he heard about Post Theatrical, he started adapting it one word at a time.

“I was like, ‘Wait a second,’' he recalled. “I just wrote an entire 200-page play. And we don’t have to do this, but I’m gonna say, we can just make a mail play out of this thing that I wrote.”

Working with fellow theater students, he mined the project for its inherent suspense. He started animating it through iMovie, a process he said is arduous because the technology slows down and crashes a lot. Wiedenmann helped him voice it. As it took shape, Gregory said, he got excited about the possibility of sharing it with a wider audience. While some works will go out by mail, others will live on the website Wiedenmann is designing. McAfee said he’s still deciding which will go out and which will be accessible online.

Artwork by Naamy Castillo. Photo Courtesy of Charley McAfee and Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School.

Gregory’s classmates have also been collaborating with each other even across the distance (some, but not all, returned to in-person classes starting April 5). Initially, junior Sofía Carrillo was skeptical of the project. When schools went remote last year, she struggled to adjust. Online classes weren’t much of a replacement for live theater, she said. Then McAfee presented the Post Theatrical concept.

“Mr. Mac comes up to us and is like, we’re going to do this play-by-mail project, and I was like, okay,” she said. “At first I was very confused, because I did not know what the heck we were doing.”

She’s glad she rolled with it, she said. Using The Purge movies as her source text, Carrillo and her team wrote, recorded and designed a series of prompts all from the second person point of view, so a reader would interpret them as choose-your-own-adventure-esque commands. Using a mix of letter writing, Google forms, and audio prompts, they informed readers “that you have a certain number of hours to complete these three tasks.”

The team got creative: in one prompt, an actor lowers their voice to sound distorted and secretive. In another, a listener can hear sirens in the background. Carrillo said it encouraged her to think outside of the work she normally does.

“Never would I have written something like The Purge,” she said.

She’s not alone. The longer Cazarin worked on the project, the more he was drawn to the idea of letters as a frightening, old-timey device that could ratchet up the suspense of his murder mystery. The work is set in 1978, the same year that real life serial killers Dennis Nilsen, Gerald Parker, Andrei Chikatilo, and Jeffrey Dahmer all committed their first murders. In the play, both the killer and the people in his orbit send out messages to the audience, revealing the psychology of a madman in segments. Cazarin, who describes himself as a generally upbeat person, pushed himself to write in a completely different style.

“It looks like there’s kind of an old style to it,” he said. “I’ve never delved so dark into a character, and it’s been pretty fun to write as a different character. As a group, we’re pretty close to finalizing it. Once it sends out, it’s gonna look pretty phenomenal. It’s such a great story.”

%20Zahir%20Maloney.jpeg?width=933&name=How%20I%20Feel%20in%20the%20Days%20of%20Covid%20(Sep%208,%202020%209_40_33%20AM)%20Zahir%20Maloney.jpeg)

Artwork by Zahir Maloney. Photo Courtesy of Charley McAfee and Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School.

In addition to the new multimedia plays, students in both theater and creative writing have written letters reflecting on what they’ve lost and found in the past 13 months. Cazarin, Wiedenmann, Carrillo and Gregory—all of whom are studying theater—described the prompt as cathartic. Cazarin told readers about making a new friend during the pandemic. Gregory reflected on what he had learned “during this quarantine period.” Wiedenmann wrote on her newfound interest in activism, through which she helped organize a rally on Juneteenth last year.

Not until Carrillo was writing did she realize that “I had a lot to say in that letter … it was nice to vent out on paper.” Following the prompt, she wrote about walking down a dark tunnel, trying to find the light at the end. She focused on her less-than-successful attempts at online learning and discovery of self-care, including a daily workout and yoga practice that she now refers to as “my best friend.” She told her readers that she could see the light, even though she hadn’t reached it. She addressed the letter to “Dear lost soul” as a reminder to herself that “I was this lost soul, but now I’m not.”

McAfee said he’s hoping to have close to 100 letters by the time a website launches at the school later this month. Of students asked to write letters, some have chosen not to share their work, and others never turned the letters in. Wiedenmann is thinking of designing the website with the image of a tree, where some branches are heavy with letters and others are bare to represent the voices that aren’t there.

“I just wanted to reiterate how amazing it’s been,” Rice said to students at the end of a recent Zoom call. “These are commissioned works. I went to Charley, and Charley went to his students to commission this work ... These are the voices that are going to be heard. That makes me feel like we have a light at the end of the tunnel, and it’s all of you.”

Tickets for Lost and Found: Coming of Age in a Pandemic are available here through April 30.