Downtown | Institute Library | Politics | Presidential Election | Arts & Culture | COVID-19

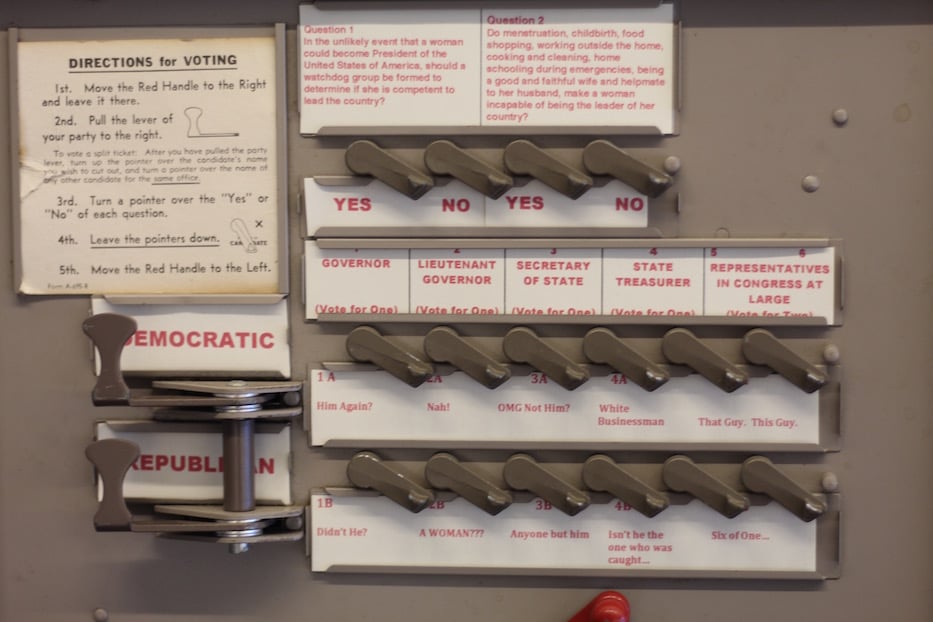

| Linda Lindroth and Zack Newick’s Suffragium pro mulieribus. Modified automatic voting machine. In an accompanying label, Lindroth explains that she used an automatic voting machine in the 1990s, when Zack was accompanying her as a kid. Lucy Gellman Photos; all work by the artists in the show. |

The text is so small that it’s easy to miss. On a steel gray background, 16 levers hang down like little legs, waiting for someone to flip them. In red print, people learn who and what they’re voting for: choices for governor, lieutenant governor, secretary of state, treasurer and congressional representative scroll across one row.

The options are ominous and cheeky all at once: candidates include “white businessman,” “OMG Not Him,” “That guy,” "This guy," and perhaps most timely, “Anyone but him.” At the top of the box, a measure reads: “In the unlikely event that a woman could become President of the United States of America, should a watchdog group be formed to determine if she is competent to run the country?”

Linda Lindroth and Zack Newick’s Suffragium pro mulieribus is part of Declaration of Sentiments, the latest exhibition at the Institute Library and the first since COVID-19 closures hit New Haven earlier this year. Named after the 1848 suffragist document of the same name, the exhibition is an exploration and sometimes stinging critique of the 19th Amendment, a heralded and imperfect political document that turned 100 earlier this year.

The show runs in the Institute Library’s upstairs gallery through Dec. 15. Curator-in-residence Martha Lewis is working to make it accessible to both online viewers and those who attend the library in person; she also plans to hold RBG-related crafting activities around Halloween and a talk with author and art historian Katherine Manthorne next month.

| Top: Martha Lewis. Bottom: Portraits of Frederick Douglass and Anna E. Dickinson by Brenda Zlamany. |

In a win for the show and its viewers, it is told largely through a historical lens, with an emphasis on material culture and archival sources. From both Lewis and research assistant Ava Hathaway Hacker, narrative sections spill out across the gallery, telling a story of suffrage that is inextricably tied to abolition, systemic racism, movements overseas, and white supremacy that continues today.

While the building feels a little like a house museum—that smell of dust and old wood is baked into the room, even on days with the windows open—there’s nothing slow or stagnant about it. The room seems to breathe, as a video from The Feminist Letters runs on a synthy loop in an adjoining hallway.

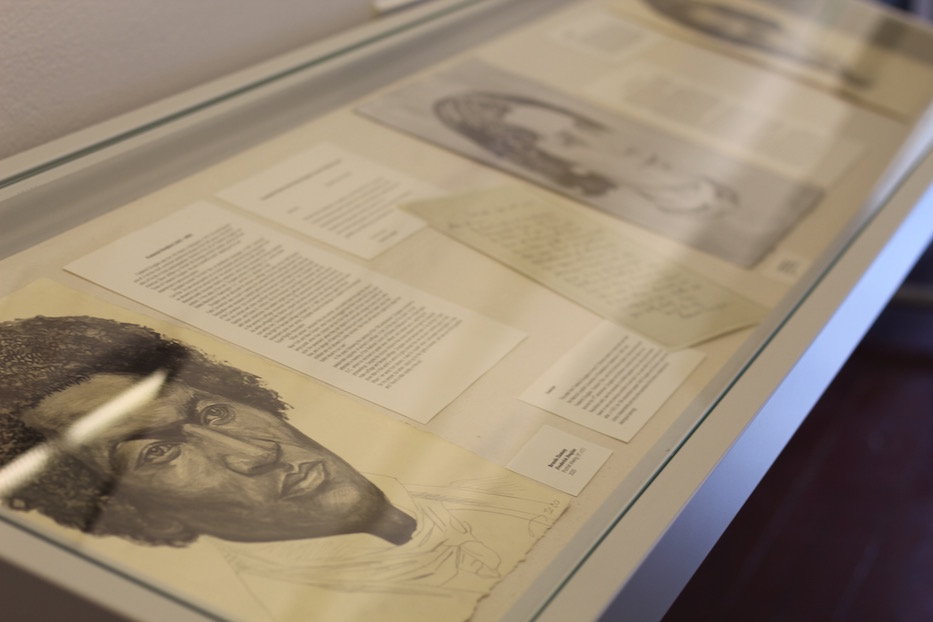

History takes the wheel, but the artist in Lewis drives much of the show’s heart. In a glass case close to Suffragium pro mulieribus, drawings by the Brooklyn-based artist Brenda Zlamany stare back: Frederick Douglass, Anna E. Dickinson, Grace Greenwood (a.k.a. Sara Jane Lippincott) and Otelia Cromwell, who became the first Black woman to receive a doctorate from Yale University in 1926.

| Top: Anna E. Dickinson by Brenda Zlamany. Bottom: Detail of Sasha Chavchavadze’s Her Words. |

The first three are enmeshed with the library’s 194-year history: they all spoke there in the second half of the nineteenth century. While Cromwell did not, she likely interacted with the Institute Library during her time in New Haven, which came almost 90 years after the library first allowed women through its doors in 1835.

Some—like Douglass, on whom many a library devotee has waxed poetic—may already be well-known fixtures in the Chapel Street building. But others are less so. Dickinson and Greenwood are not household names, although Lewis said she would like for both of them to be.

As one of six kids growing up in nineteenth-century Philadelphia, Dickinson supported abolition from a young age; Douglass was in fact a visitor in her childhood home, and the two later wrote to each other (one of their letters is in the show). By her teens, she was defending both women’s rights and abolition before the American Civil War. As the war began and raged, she traveled across the New Hampshire and Connecticut speaking out for political candidates, including a trip to Hartford that then likely brought her through New Haven and to the Institute Library.

One year after the war ended, she joined Douglass and Theodore Tilton for a discussion at the National Loyalists Convention in Philadelphia, in what Lewis called “the early stirrings of the 15th Amendment.”

But she was also dismissed as loud, inappropriate for her sex, and insane, ultimately institutionalized by people in her own family. While she later regained her freedom and sued those responsible, “Dickinson’s legacy would remain tarnished by this event,” Lewis wrote.

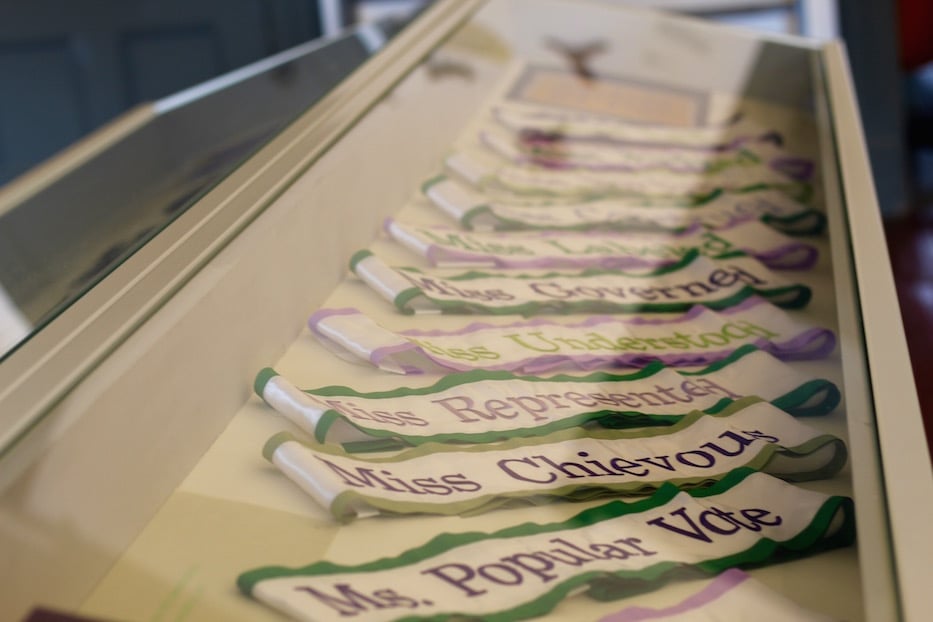

| Top: Victory Garden Collective, MISS 2017. Portfolio of 15 embroidered sashes. Bottom: A section of Ava Hathaway Hacker's timeline. |

An abolitionist like Dickinson, Greenwood straddled the line between writing, reporting, and advocacy for much of her life. In a case beside an archival, rescued film strip—Florence Fleming Noyes as a flickering, white-clad Lady Liberty—Lewis has included several of her manuscripts as well as a text on her life and work.

In writing on each of them, Lewis and Hacker have focused specifically on their relationships with each other, with abolition, with equal voting, and with suffrage—particularly differences of opinion over the 15th Amendment in 1870 and the 19th Amendment 50 years later in 1920.

The first gave Black men the right to vote; the second gave some women the right to vote. Both were incomplete in their approach: Black people were still barred from voting until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and are still disenfranchised at the polls today. That’s also true of non-white women, particularly Native and Asian-American women who were kept from the polls because they were not recognized as fully human.

It feels fitting nestled near Sasha Chavchavadze’s contemporary Her Words and a door that is plastered with The Feminist Letters. In the first installation, Chavchavadze pays tribute to the writer and journalist Margaret Fuller, who was killed in a shipwreck in 1850. Following her death, several male colleagues including the writer Ralph Waldo Emerson “distorted Fuller’s life and work, effectively erasing her legacy.”

The work, embroidered on fabric and mounted on what looks like driftwood, returns some of the author’s agency to her. Using craft and multimedia assemblage—both mediums often relegated to the feminine realm—Chavchavadze also shows how little of this momentous woman is left. The work fits so neatly, so politely over a shelf of books that a viewer must stop and remind themselves that it’s there.

| The Feminist Letters, a project of Y&R New York, which were published in January 2018. |

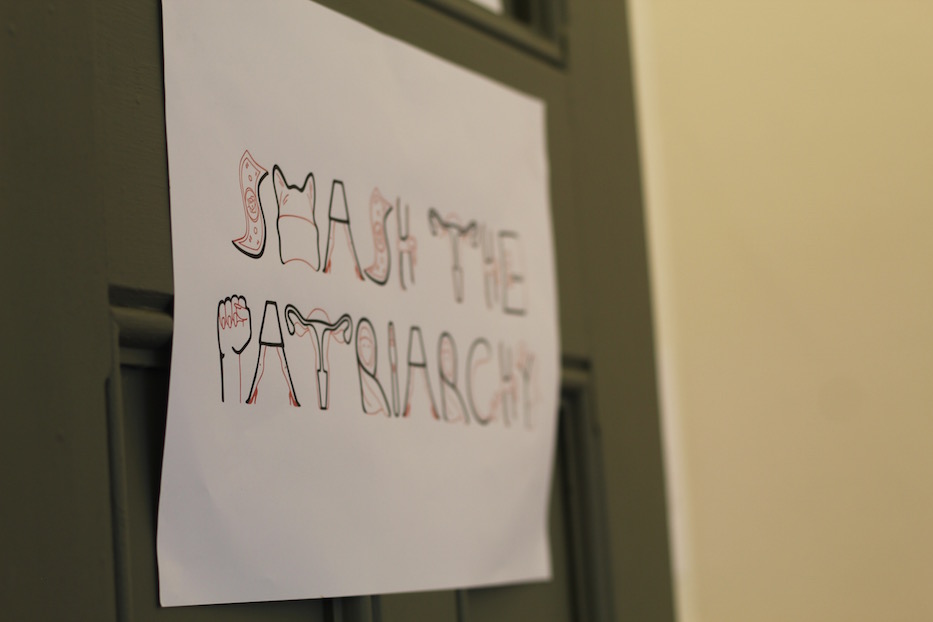

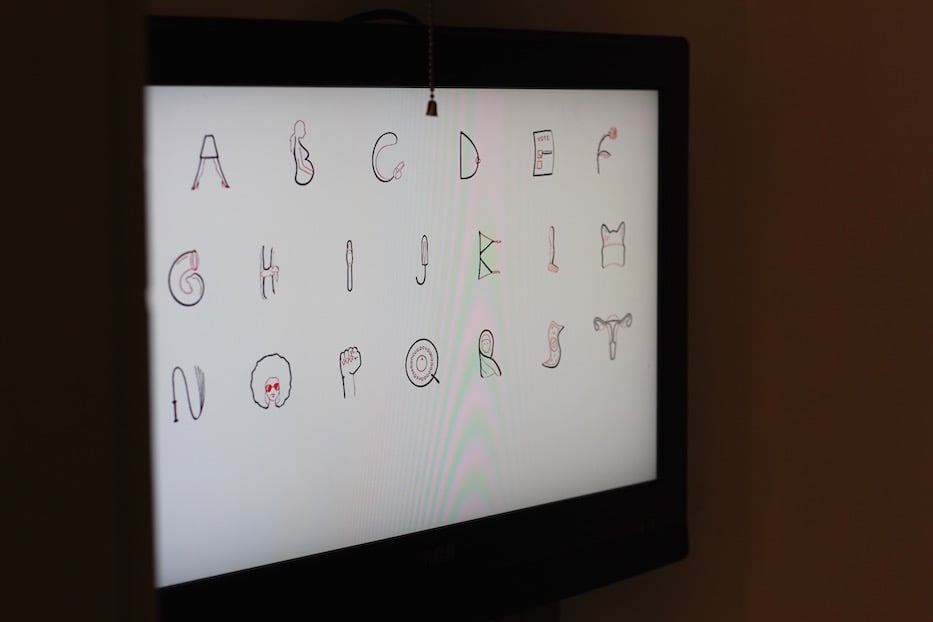

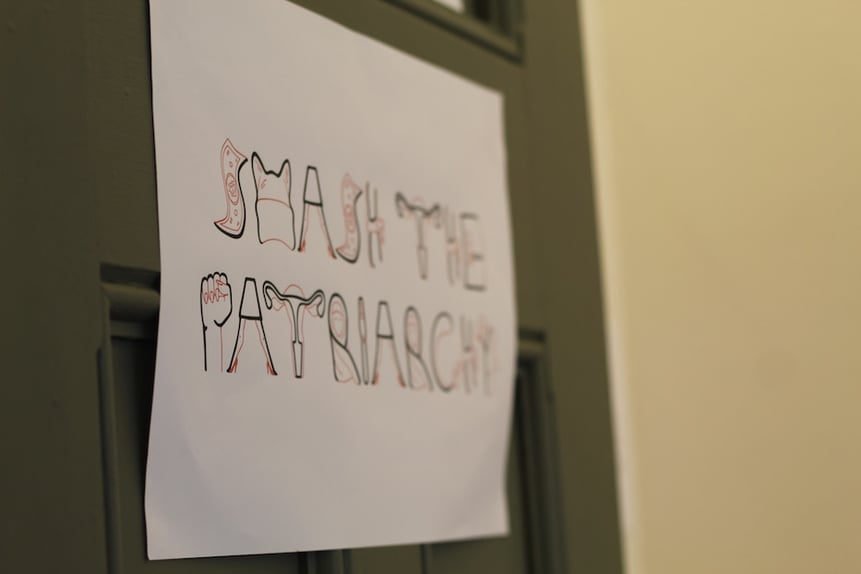

Beside it, the latter is a typeface designed with crowns, copper coils, fallopian tubes, diva cups, full afros and pregnant bodies that spell out sentences like “Smash The Patriarchy,” “Women Belong In Politics” and “No Gag Rule.” The font was born in early 2018, just in time for the second annual Women’s March on Washington and across the country. It is in good company: Lindroth’s modified voting machine and an edition of 15 sashes from the Victory Garden Collective feel like parts of the same whole.

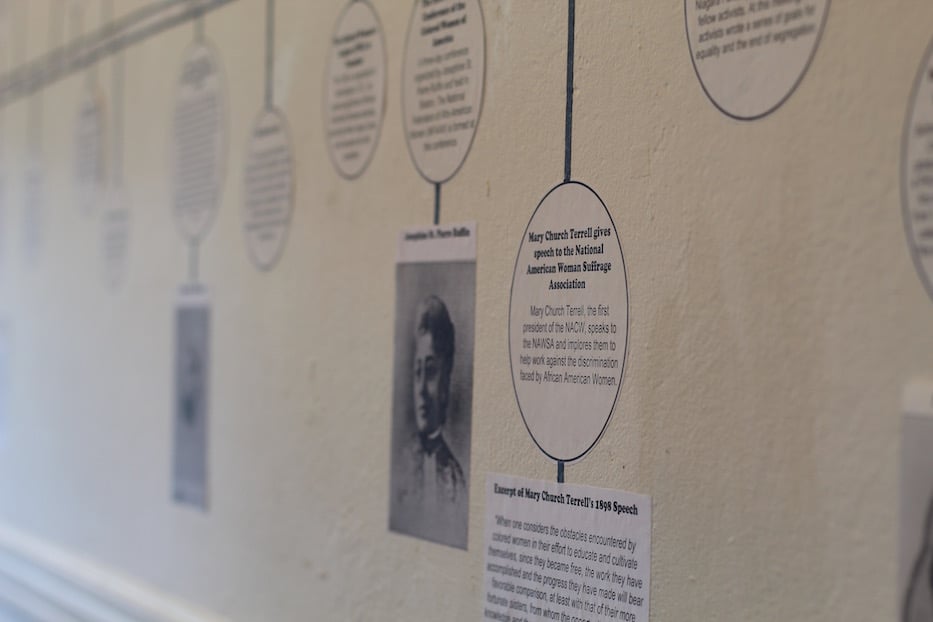

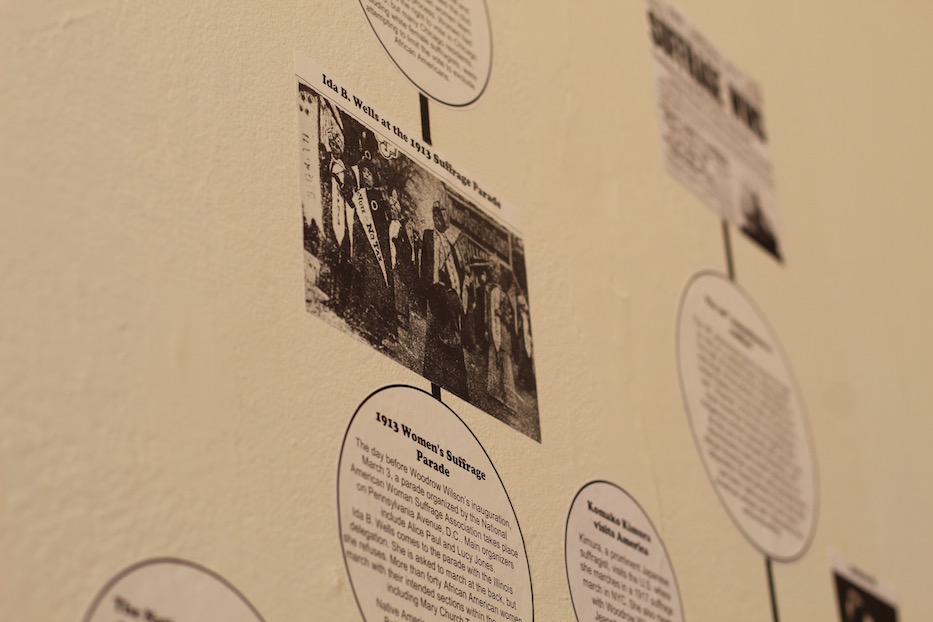

Across the gallery—but very much on the same wavelength—is a timeline that traces the fight for the 19th Amendment from 1789 to 1975 (“I could have kept going,” Hacker said—but the wall ended). In building the timeline, she concentrated on not the clean-cut narrative of forward progress often written into history books, but the women that the amendment left out, and is still leaving out today.

“It is not unusual to treat the 19th amendment as a final victory in the fight for female suffrage, but this ignores the millions of women that the amendment left disenfranchised,” she wrote for a label that accompanies the show. “The 19th amendment removed sex as a barrier from the vote, but it was just one step towards truly universal female suffrage. Indeed, women of color fought a far more complicated intersectional battle, facing barriers not just of sex but of race as well.”

The timeline—installed in unassuming white paper—bears witness to that history. There are the stories, for instance, of Francis Ellen Watkins Harper, who in 1866 addressed the National Woman’s Rights Convention alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. While speaking to attendees, she spoke out on the impossibility and pain of her position, which asked her to choose between voting rights for Black men and the mostly white women who rallied against them.

Hacker takes an intersectional lens: she traces the schism—which feels both inevitable and still persistent—between the National American Suffrage Association and the National Women’s Suffrage Association. As momentum was building around the 15th Amendment, suffragettes split: there were those who believed in men’s universal right to vote, and those who believed that it came at the expense of white women. It was a divide that made clear the need for groups like the National Association of Colored Women—and still persists today.

Hacker introduces names like Mabel Ping-Hua-Lee, Mary Church Terrell, and Zitkála-Šá,. She mourns Harry and Henriette Moore, Civil Rights Activists who were killed in 1951 by the Ku Klux Klan when a bomb exploded in their home on Christmas Day. There is information on felon disenfranchisement that continues today, Indigenous women written off by their white peers and white U.S. government, and accounts of misogynoir long before it was called misogynoir.

“Though the timeline ends with the Voting Rights Act of 1975, it aims to show that the struggle for equal suffrage in America is not a movement with a start and end date, but a weaving path with victories and obstructions that continues up to today,” Hacker wrote.

The history does more than contextualize the centenary: it rounds out a version of the suffrage movement that is not discussed enough, in which white women (usually straight and cisgender, although as Lewis noted “they really were all sleeping with each other” after a certain point) believe that their gain must come at another group’s loss. There is a need for this truth-telling: whiteness is, and has long been, proximate to power. If white women can’t encounter and undo their own worst selves, then they will hold all women back.

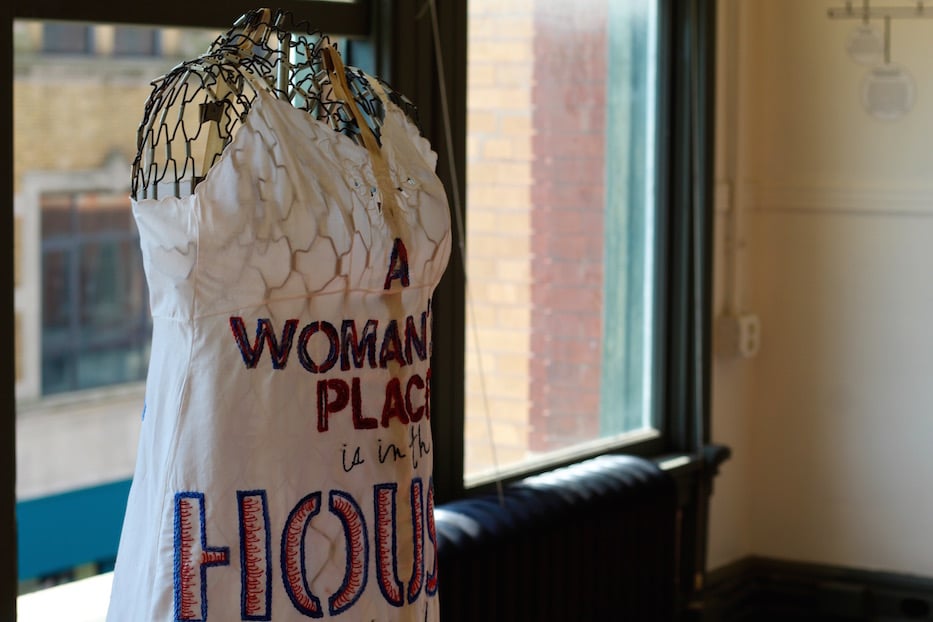

| Top: Judy Polstra’s A Woman’s Place. Bottom: Ann Kennedy//Auntie Gibson Belshe. Auntie Gibson Belshe (1884-1984) driving in a parade of suffragettes at the Cloverleaf Fair, Richland, Missouri. |

Throughout the gallery, new art fits in with the old. Beside the timeline, Lewis has installed a bright, tidy display of ephemera beneath glass, with period cartoons, postcards, photographs and an oval “I Voted” sticker. Some images feel startlingly timely, despite their age: there’s a hen who leaves her eggs cooling as she gets up and leaves the coop, a chagrined rooster calling out behind her. A 1901 stereograph threatens that if women get the right to vote, all of them will start walking around in bloomers and stockings, ankles exposed.

They work in conversation with several pieces that riff on the history of craft, embroidery, and quilting, all of which are often regarded as folk arts rather than fine arts. Judy Polstra’s A Woman’s Place takes on the standard of domesticity, with the now-oft-repeated refrain “A Woman’s Place is in the House and the Senate” embroidered in pink, red, blue and black on a white summer slip.

In a sun-soaked corner, Katrina Majku presents a cross-stitch kit dedicated to voter registration. A huge cyanotype from artist Margaret Roleke hangs on an opposite wall, perhaps a nod to early photography practitioner Anna Atkins that also looks like Mattel’s worst nightmare.

In doing so, Declaration Of Sentiments pushes beyond a self-congratulatory second wave feminist loop into something much more interesting. With history on her side, Lewis shows that white, mainstream feminism—which is still enacting violence on women and men of color, LGBTQ+ and particularly trans women—is a bloated ouroboros that needs to spit out some of its own poison before another cycle of rebirth.

| Top: Rita Valley’s Vote Goddamnit. Bottom: Collection of Laura Boyer. |

It comes full circle in pieces like Rita Valley’s Vote, Goddamnit, an embroidered collage from this year that fuses fake pearls, shiny, faux alligator skin and blue plastic as it hangs beside a 1913 poster encouraging votes for women.

Both are a call to arms, spread across a little over a century. The poster comes from Institute Library Board Member Laura Boyer, who received it from her grandmother. Close to it, Valley reminds viewers that over 100 years later, voters still have everything to lose.

“During this election it is particularly important to look back at history, at the hard-won battle that others fought for us, and to make our voices heard loudly and collectively,” she has written in a statement that accompanies the exhibition. “This means truly listening to each other, joining forces and demanding equality, justice, and representation within our government.”

Find out more about the Institute Library, including upcoming events, here.